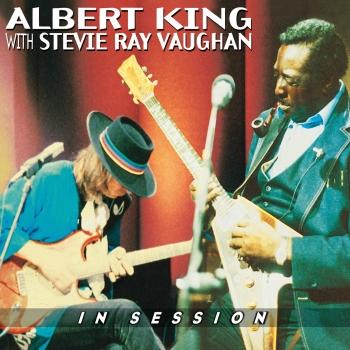

Albert King & Stevie Ray Vaughan

Biography Albert King & Stevie Ray Vaughan

Albert King & Stevie Ray Vaughan

While there is no denying the immeasurable debt that modern blues and rock musicians owe to T-Bone Walker, the first bluesman to plug a guitar into an amplifier, and to B.B. King, who added sustained feedback and more to Walker's innovations, Albert King was clearly the most influential blues guitar stylist from the mid-1960s on. Born April 25, 1923, Albert had begun his career as B.B. King disciple and, for a time, even claimed to be B.B.'s brother. (Both men were born in Indianola, Mississippi.)

By the time Albert signed with Stax Records in 1966, however, he had developed a highly personal guitar style marked by economical, rhythmically propulsive single-note lines and a razor-sharp tone produced by picking with his left thumb while bending wildly with his right fingers on the strings of a right-handed Flying V guitar turned upside down and tuned to an open E minor chord. His ground-breaking, soul-imbued recordings for the Memphis record company from 1966 to 1973 defined the state of modern blues during that period and had a vast impact on guitar players on both sides of the Atlantic. Not only did Albert's signature style alter the approaches of such already established blues guitarists as Otis Rush and Albert Collins, but it had a tremendous impact on younger players like Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Jimi Hendrix, and particularly Stevie Ray Vaughan.

Stevie was born (October 3, 1954) and raised in the Oak Cliff section of Dallas, the same part of town in which T-Bone had grown up decades earlier. Stevie idolized Albert. Even before he was in his teens, Stevie had been captivated by the Mississippi guitar masher's torrid tone, incisive phrasing, even the rocket-like shape of Albert's instrument. The boy had other musical heroes--most notably older brother Jimmie Vaughan, as well as Lonnie Mack and Jimi Hendrix--but it was Albert's influence that would remain the most pervasive throughout Stevie's career.

One of 13 children, Albert was raised by his mother in Forrest City, Arkansas. His first "guitar" consisted of a wire nailed to the wall of his house; he picked it with a bottle. Later, he bought an acoustic guitar for $1.25 and eventually graduated to an electric model purchased for $125 at a pawnshop in Little Rock. After practicing for a few years, he began sitting in around Osceola, Arkansas with a group called Yancey's Band. "They learned me my chords and what key was what," Albert recalled 1983. "I didn't know but two or three songs."

Driving a bulldozer during the day, Albert soon formed his own band, the In the Groove Boys. "I learned 'em those three songs that I knew," he explained with a chuckle, "and we'd play 'em fast, slow, and medium, but we got over."

After singing gospel with the Harmony Kings in South Bend, Indiana and playing drums for Jimmy Reed in Gary, Albert made his first record, "Bad Luck Blues," for the Parrot label in Chicago in 1953. The title proved prophetic, however, and he returned to Osceola for a while, then settled in East St. Louis, Illinois, where he began recording for Bobbin in 1959. He scored his first national hit, "Don't Throw Your Love on Me So Strong," two years later on the Cincinnati-based King label.

Albert didn't return to the charts until 1966, when his Stax recording of "Laundromat Blues" became one of that year's biggest blues hits. The innovative melding of Albert's dry, husky baritone voice and incendiary lead guitar with the Memphis firm's crack rhythm and horn sections brought blues into the soul era. His seminal Stax singles, which also included "Crosscut Saw" and "Born Under a Bad Sign," were initially bought primarily by African Americans. With the introduction of "underground" FM radio in 1967, Albert began attracting white listeners—who had been primed by Eric Clapton's incorporation of Albert's licks and even entire solos into his popular sides with Cream—in increasingly large numbers. His 1968 debut at San Francisco's Fillmore Auditorium solidified his crossover following. "People had been waiting to hear me play a long time before I even showed my face out there," recalled Albert, who remained until his death one of the few blues artists to consistently attract substantial numbers of both black and white fans.

At the In Session taping, 60-year-old Albert ruled over the proceedings like a benevolent father, retaining control while allowing his 29-year-old guest loads of solo space in which to display his awesome command of the electric guitar. Stevie avoided flaunting his prowess, however, and instead delivered some of the most deliciously restrained playing of his career, laying back when his mentor dictated, turning up the heat only when Albert deemed it appropriate. The interplay between the two blues masters is uncannily empathetic, and Albert's fans will find special pleasure in hearing him play rhythm parts at such length. At one point between tunes, Albert complained about problems with his guitar strings, then told Stevie, "I'm about ready to turn it over to you.... I've got to sit back and watch you."

Albert was, in a sense, passing the torch to Stevie. The following month, in January 1984, Albert and his band traveled to Fantasy Records in Berkeley, California to record I'm in a Phone Booth, Baby. It would be his final album. He never did retire from the road, however, and continued touring until his death from a massive heart attack in Memphis on December 21, 1992. Albert was 69 and had enjoyed a full life in the blues.

Stevie wasn't as fortunate. At the height of his career, on August 27, 1990, he was killed in a helicopter crash at Alpine Valley, Wisconsin. He was 35.