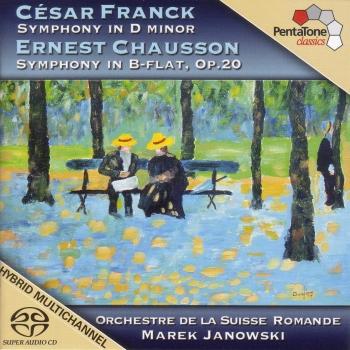

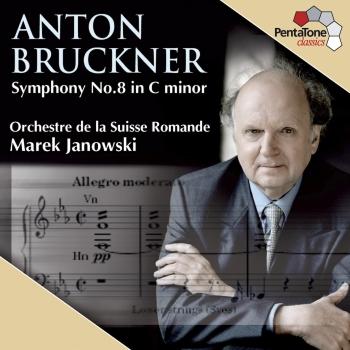

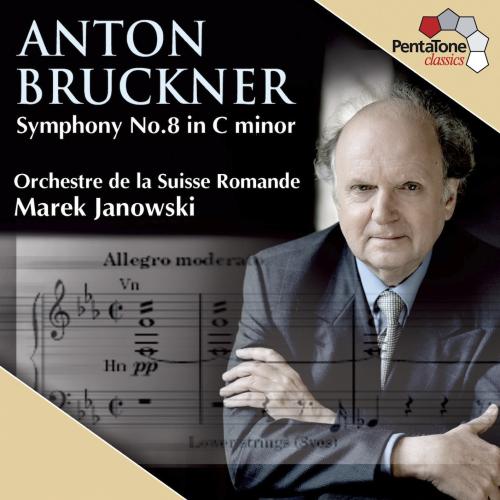

Bruckner: Symphony No. 8 in C minor (1890 Version) Nowak Edition Orchestre de la Suisse Romande & Marek Janowski

Album info

Album-Release:

2010

HRA-Release:

19.07.2013

Label: PentaTone

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Orchestral

Artist: Orchestre de la Suisse Romande & Marek Janowski

Composer: Anton Bruckner (1824–1896)

Album including Album cover Booklet (PDF)

- Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 8 in C minor, WAB 108 (1890 version)

- 1 I. Allegro moderato 15:00

- 2 II. Scherzo - Allegro moderato 14:52

- 3 III. Adagio 26:14

- 4 IV. Finale - Feierlich, nicht schnell 23:42

Info for Bruckner: Symphony No. 8 in C minor (1890 Version) Nowak Edition

This is the second version of this symphony. It took Anton Bruckner slightly more than three years to complete his Symphony No. 8 in C minor. Or, to be precise, to complete his first version of this symphony. Never yet had Bruckner spent so much time on a single work. And if one adds to this the revision process of the second version (as recorded here), then the creation of this composition covered a period of almost six years, namely from 1884 until 1890.

Thanks to the overwhelming success of his Symphony No. 7, Bruckner was in an exuberant state of mind. He had finally achieved the breakthrough for which he had longed! And in this mood he set to work with great intensity on his new composition, which progressed rather slower than usual. This was due to a number of reasons: for example, the impaired physical health of the 60-year-old composer, the unaccustomed strain caused by numerous performances, and the extra work surrounding the first publication of his seventh symphony. As is apparent from the chronological period of creation (without going into great detail), he did harbour various doubts concerning the concept of his Symphony No. 8, not in the last place due to the pressure of unexpectedly high anticipation: he wanted nothing more than to outdo his seventh symphony. Nevertheless, he managed to complete the score by August 10, 1887: and as we know that he began sketching his Symphony No. 9 just two days later, clearly he was not thinking about further revisions at that moment – let alone, about any new version...

Bruckner lay the success of his Symphony No. 7 mainly at the door of the conductor of the Munich première, Hermann Levi; and in September 1887, he sent the score of his eighth symphony to his 'artistic father', full of cheer and hope, accompanying it with the following words: 'May it find favour in your eyes!

I cannot possibly describe the pleasure

I derive from anticipating a performance of the work under the direction of the same maestro.' However, as he replied, Levi was not able relate in the slightest to the new work – and Bruckner felt as if his world was collapsing. After having felt so elated, he now descended to the depths of despair. Yet Levi, who criticized in particular the 'stereotypical structure' – as well as the instrumentation and the finale – concluded his letter as follows: '… a revision may prove highly worthwhile'. Subsequently, Bruckner became obsessed with the revision (not for the first time): in fact, not only did he totally revise his Symphony No. 8, he also created a third version of his Symphony No. 3, as well as the Vienna version of his Symphony No. 1.

As far as his Symphony No. 8 is concerned, it does appear that there were a number of outside influences, primarily Levi – clearly, Bruckner wanted to have him conduct the première. Thus, in February 1888, he wrote to the conductor as follows: 'Admittedly, I have good reason to be ashamed of myself – at least, for the last time – with regard to my eighth symphony. What an ass I was! It now looks very different.' Bruckner, an ass? This much-quoted passage from a letter refers to a previously mentioned occurrence, which gains significance in reference to the new version: whilst working on the Adagio of the first version, Bruckner had once again completely revised his already finished sketches – perhaps an indication of the first doubts the composer was beginning to harbour with regard to the concept of the first version? And indeed, after the completion of the work in 1890, it did look 'very different' – the first three movements had been entirely rewritten in new manuscripts, whereas changes in the finale had been incorporated into the existing score. Leopold Nowak, general editor of the two versions in the context of the complete Critical Edition, pointed out that there were differences – albeit at times minimal, or just barely audible – in virtually every measure. In particular, Bruckner made massive changes to the instrumentation, which Levi had criticised as 'impossible'; and in his second version he clearly homogenized the sound by introducing triple woodwinds and extra horns (ranging from five to eight) in all movements; furthermore, he included three harps in the Adagio in the Scherzo-Trio, a most distinctive feature. Research into the 'character' of the sound demonstrates that the more individual sound of the first version made way for the ideals of the 'popular Wagnerian sound characteristics' (Manfred Wagner) in the second.

In addition to these changes in the 'inner spirit' of the work, Bruckner also rethought his concept of the work, with far-reaching consequences. Apparently, he had experienced a special problem with the end of the first movement – and a special problem demands a special solution. He came up with a solution that was unique in his oeuvre: instead of as usual allowing the main theme to explode in fff into the coda, he did the opposite and ended the movement in ppp, gradually decomposing the main theme up until the final chromatic phrase of the opening motif. The usual apotheosis fails to materialize. The movement now – in the second version – almost fades away, thus resolutely referring to the beginning of the work, which struggles up from the deepest of abysses in utter tonal suspension. For the first time in his Symphony No. 8, Bruckner also juggles the inner movements: he first presents the remarkably timid, yet at times thematically 'stiff' Scherzo; then he follows on with the highly expansive Adagio, full of tremendous intensifications. Due to this interchange, the scales are tipped towards the end of the symphony – thus, the second part of the work (the Adagio and Finale) gains not only in length, but also in significance. Ultimately, Bruckner develops here his idea of a Finalsymphonie (= finale symphony), with which he had first experimented in his Symphony No. 5. He concentrates on the finale, utilizing all his compositional strengths and developmental skills. And at the conclusion of this movement, the symphonic cycle of the eighth is finally brought full circle: here, the main themes of all four movements are gathered together simultaneously and presented once again; however, now in radiant major. The apotheosis, at first denied to the opening movement, is now allotted almost superhuman dimensions. Here, absolute music comes to terms with itself.

Undoubtedly, Bruckner's mightiest and most monumental work is his Symphony No. 8. And yet it is full of doubts and dark abysses. Bruckner himself described the work as a 'mystery': thus, keeping this in mind, whereas one might enjoy his strange, if not abstruse 'commentaries on the substance' of the Eighth, one should still approach them with some caution. After all, far better to search for doubts, dark abysses or meanings in the score itself – for that is where one can hear the true voice of a composer – than in any 'programmatic' proclamation.

Ultimately, in his Symphony No. 8, Bruckner demonstrates both his perfection and conquest of the symphonic genre: for instance, by making radical progress in hitherto unheard-of terms in the harmonic realms, transporting the work to the limits of tonality and beyond. (Only Mahler was to take this a logical step further.) He contrasts these unstable harmonic structures with extremely powerful rhythmic elements, in order to create a 'counterpoint between stability and instability' (as aptly described by Mathias Hansen), which tosses the audience about in a vexing manner. The tremendous development of the complex themes, and thus the resolution of their classical-romantic duality, exceeds the limits of the genre.

Can we perhaps discover, behind this crossing of borders, the abysmal depths and fears of the composer? And if so, how does one link the common image of Bruckner held by both contemporaries and later generations – namely, that of the dim fool, the uncouth country bumpkin, the unworldly provincial – to this music? After all, Bruckner does not compose in an obsequious manner; rather as an anarchist, or a commander in battle, leading his imaginary orchestral armies seemingly without effort through various situations and emotions such as powerlessness, belief, desire, happiness, loneliness and fear. One might even hear a Zusichselbstfinden (= coming to terms with himself) in the coda of the Finale. Or perhaps not. That is exactly why the Symphony No. 8 is a true 'mystery'; not just to its audience, but also to its creator.

On December 18, 1892, Hans Richter led the Vienna Philharmonic in the première of the work. The performance must have been overwhelming, and was described by Hugo Wolf as follows: 'The symphony is the creation of a giant, and in spiritual dimension, prolificacy and volume, it towers above all other symphonies written by the master. [...] It was a complete victory of light over darkness, and a storm of enthusiasm broke loose as if powered by elemental forces.' Reactions nowadays are not that different.

'Janowski's conducting of the opening movement is impressive...steering a flexible course commandingly to a thrilling climax that finds the Suisse Romande Orchestra powerful but not coarse...At the close Janowski is rare among conductors in allowing the ticking clock to 'stop dead' (in other words there isn't even a hint of a ritardando) and this is exactly as it should be.” (International Record Review)

“As an interpreter of Bruckner, Marek Janowski steers a straight centre course...and this Eighth is a good example of how well that approach can work...I don't think I've ever heard the finale bound in a more perfectly judged tempo, accelerating almost imperceptibly for the opening bars, then steadying so that brass make their full effect...I can't imagine anyone who isn't especially concerned with strongly personalised interpretation being disappointed.” (Gramophone Magazine)

Orchestre de la Suisse Romande

Marek Janowski, conductor

No biography found.

Booklet for Bruckner: Symphony No. 8 in C minor (1890 Version) Nowak Edition