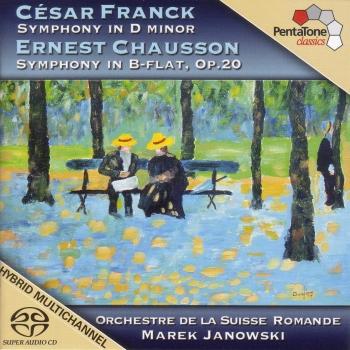

Bruckner: Symphony No. 7 in E major (1881-1883) Nowak Edition Orchestre de la Suisse Romande & Marek Janowski

Album info

Album-Release:

2011

HRA-Release:

19.07.2013

Label: PentaTone

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Orchestral

Artist: Orchestre de la Suisse Romande & Marek Janowski

Composer: Anton Bruckner (1824–1896)

Album including Album cover

- Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 7 in E major, WAB 107 (1885 version, ed. L. Nowak)

- 1 I. Allegro moderato 21:12

- 2 II. Adagio. Sehr feierlich und sehr langsam 21:42

- 3 III. Scherzo - Sehr schnell 09:52

- 4 IV. Finale - Bewegt, doch nicht schnell 13:15

Info for Bruckner: Symphony No. 7 in E major (1881-1883) Nowak Edition

In the more than 100 years since his death in 1896, the appraisals by musicologists, critics and the public at large of Anton Bruckner, the man, and Anton Bruckner, the composer, have consistently been radical in character. From the beginning, the standpoints of Bruckner disciples and Bruckner haters have been virtually irreconcilable. Few cases in musical historiography have featured such a diversity of standpoints regarding the importance of an oeuvre and its creator for European music. For the longest time, clichés and stereotypes set the tone of Bruckner reception, with Bruckner himself tending to be the focus of attention. This approach was typically accompanied by questionable characterizations which stood in the way of any objective investigation, e.g., 'God's musician,' 'Upper-Austrian peasant,' 'hero of German composition' and 'half genius, half idiot.' It was not until the 1980s that Bruckner's musical oeuvre, as such, started being subjected to greater scrutiny (than its creator). In particular German-speaking musicologists, with the help of detailed work analyses, began to approach the phenomenon of Anton Bruckner using a method which set aside the questionable anecdotes and speculations surrounding the personage, Bruckner, and concentrated above all on the facts: i.e., the surviving musical texts (in which connection the version problem became the foremost priority). A prime example of this new approach to Bruckner is the 'Bruckner Handbook' (2010), overseen by Hans-Joachim Hinrichsen. In this excellent compendium, prominent Bruckner specialists comment on the composer's works under the unifying theme, 'Bruckner, the great stranger'. The aim of the authors was to 'blaze' a new trail, one 'off the beaten track,' and the handbook indeed has the potential to promote realism and objectivity in today's Bruckner reception and, as a result, significantly to broaden its horizons. In the work's almost 400 pages, the entire oeuvre is subjected to detailed analyses, which, amongst other things, shed much light on the connections between the two great blocks in Bruckner's compositional production - the large-scale sacred choral works and the symphonies, respectively.

Symphony No. 7 in E-major was composed between 23 September 1881 and 3 September 1883. The work's reception would signify a clear turn for the better in the life of Anton Bruckner. It would also mean a break-through to prominence and instantly earn the almost 60-year-old composer the status of a musical authority, from now onwards both respected and heeded. What had happened? On 27 February 1884, Bruckner's students, Ferdinand Löwe and Josef Schalk, had presented, at Vienna's Bösendorfersaal, a piano four-hands version of the work, immediately winning over the Leipzig music director, Artur Nikisch, who had not only participated as an orchestra member in the Court Opera-Orchestra's premiere of the Second Symphony, but was, as well, extremely open toward contemporary music. Nikisch expressed his enthusiasm thus: 'Since Beethoven, nothing bearing even a slight resemblance to this has been composed. What is Schumann in comparison!' The Munich court music director, Hermann Levi, pledged to do all he could to ensure a performance of the work: 'By the time the day of the concert has arrived, half the city will already know who and what Herr Bruckner is, whereas up to now – I must observe to our shame – no human being has known this, including this most devoted admirer.' It would still be a few months until the world premiere, but on 30 December 1884, it finally took place, under Nikisch's baton, in Leipzig's Gewandhaus. The reaction of both critics and public was cordial. The actual break-through for the Seventh, though, came at the euphorically received Munich performance of 10 March 1885 under Hermann Levi, in the presence of the composer. Bruckner was against performing the symphony in Vienna: 'I oppose any plan to perform my 7th Symphony in Vienna, as this would, due to Hanslick et al., be pointless there.' It would be an entire year, and not until the work already had been engraved and printed, before it was finally played in Vienna, on 21 March 1886.

The Seventh is the most frequently performed of all Bruckner symphonies, and extremely popular with audiences. This undoubtedly has to do with the fact that it embodies features which clearly distinguish it from its six predecessors and two successors. Peter Gülke in the 'Bruckner Handbook': 'A comparison of this expedition with those of the Fifth and Sixth, leads to an hypothesis that the success of the Seventh is connected to its 'classicistic' tendencies toward clarity and reserve. To a greater extent than elsewhere in Bruckner, the formal structure is, with the exception of the finale, easily comprehended – this not least due to an overpowering, contouring dramaturgy of intensifications, excursions, harmonic progressions, alternations of sound groups, etc.' In no other Bruckner symphony is melodic potential exploited to such an extreme degree. The work's widely oscillating cantabile melodic progressions (e.g., the 24-measure-long main theme of the first movement or the splendid progressions in intensity of the 'sound chains' in the Adagio), its sonic homogeneity (in particular the, ceremonial tuba passage in the Adagio, with its resonances of Wagner's death) and masterful contrapuntal development (in the terse Scherzo, for example) together yield greater accessibility for the listener, this not only at the level of overall form, but at the lower levels of motivic and thematic design, as well.

Beyond all detail aspects of the composition, however, a look at the work as a whole reveals an overall-conception that is unique in the Brucknerian symphonic oeuvre. As Bruckner appears not to have striven to devise themes for the work's movements that are entirely distinct and self-contained objects, the requisite power for a final thematic break-through is ultimately far less than in other works. As a result, the relatively brief finale – as final movement typically Bruckner's location of choice for the fulfilment of cyclical coherence – remains free of violent outbursts (such as in the Fifth). In addition, Bruckner artfully uses the end of the development to obscure the entrance of the recapitulation, and even reverses the order of the themes, so that, once the closely, but subtly, related main theme of the finale has retreated, the main theme of the first movement ultimately can emerge with blinding radiance as the symphony's final apotheosis. The symphonic arch is complete, and, as a result, Bruckner's self-description wondrously fulfilled: 'in the final analysis I am only and exclusively a symphonist – I have staked my life on it [...].' Translation: Nicholas Lakides

“Janowski has forged an instrument that projects Bruckner's richly textured canvases with a combination of warmth, transparency and tonal weight, the brass sounding particularly impressive...Pentatone has provided Janowski and his Geneva forces with excellent sound. This is yet another significant step towards what I am convinced will eventually turn out to be one of the finest recorded Bruckner cycles of the 21st century.” (Gramophone Magazine)

“every orchestral department here delivers superbly, with gorgeously rich strings, mellow woodwind, and powerful brass. Janowski's conducting, too, combines a true sense of Brucknerian space with impressive purpose and drive...While there's formidable competition among recordings of this much-played symphony, this version holds its own superbly.” (Classic FM Magazine)

Orchestre de la Suisse Romande

Marek Janowski, conductor

No biography found.

This album contains no booklet.