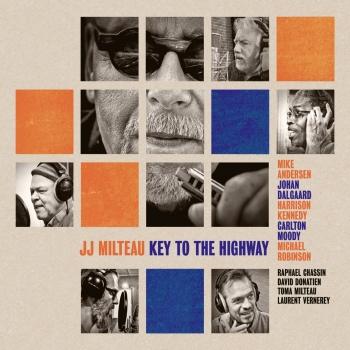

Jean-Jacques Milteau

Biographie Jean-Jacques Milteau

Jean-Jacques Milteau

Listening to one of Sonny Terry’s albums touched Jean-Jacques Milteau to the core, although he did confess, “I’d already heard a bit of harmonica…”. So we can just imagine this young Parisian born in 1950 and living in the 13th arrondissement, not far from the Porte d’Italie, and how his childhood and youth must have been lulled by one of the chromatic instruments of someone like Albert Raisner. The latter, once past the golden age of his second trio (i.e. 1947 – 1953) had now become a radio and TV star, and had been broadcasting bravura pieces such as Le Canari since 1959. Or maybe Milteau, like most of his fellow-countrymen, didn’t even know Jean Wetzel’s name but been nourished, perhaps even to excess, on his mouth organ – Jean was that enigmatic performer (1954) of Jean Wiener’s theme specially composed for the film Touchez Pas Au Grisbi. Here indeed was stuff to render the ears of a young man more sensitive, forge them even, but from there to inspiring a true vocation, there’s a whole world ! And that world is the Blues.

We can imagine Jean-Jacques Milteau much more sensitive to the You’re No Good that opens Bob Dylan’s first revolutionary album (March 1962) – and what do you bet he used to listen over and over again to the new Dylan version of the famous Freight Train Blues ? Then in October 62, Milteau fell under the spell of The Beatles’ first single Love Me Do, a Paul McCartney composition given extra polish by John Lennon with a riff on harmonica inspired by Delbert McClinton (who’d recently scored a hit with Hey Baby ! by Texan Bruce Channel [February 62]). Like most of his contemporaries, he only discovered recordings made by Cyril Davis and Paul Butterfield much later, yet as early as 1963, they were taking up position as real ambassadors for the instrument. But in February 1964, one thing our hero didn’t miss was the Rolling Stones’ first single, Not Fade Away, suffused from beginning to end with Brian Jones’ flaming harmonica, true to his own nature. “I bought a harmonica because there was some kind of rock-folk fashion at the time on the part of blokes like Dylan, the Rolling Stones, Donovan, John Mayall…”

John Mayall was on the scene from 66 and before that, in 1965, there’d been Sonny Terry and his breathtaking Lost John. From that moment on, this was the music, with that special sound, that form of expression that by common accord “could only come from the blues”. That title comes from a 1954 Folkways recording ; the label founded by Moses Asch in 1948 proposed recordings by the heroes of the folk scene at the same time – people such as Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Dave Van Ronck (all Bob Dylan’s idols)… and some survivors of the golden age of Country Blues such as Big Bill Broonzy, Blind Willie Johnson, Brownie McGhee, Jazz Gillum, LeadBelly, Josh White, Big Joe Williams, Reverend Gary Davis… Outside the USA the label was distributed by Le Chant du Monde – and this would be Jean- Jacque Milteau’s first producer.

Surprisingly enough, the harmonica was put aside or remained unknown to all those who took part in the Rock ‘n Roll revolution started by Elvis Presley, with one noteworthy exception : Bo Diddley, who took Billy Boy Arnold on board, whose incisive and decisive style on (most notably) Bring It To Jerome, Diddley Daddy and Pretty Thing struck home. When a so-called rocker wants a “blower” with him, he ‘s usually more likely to take a saxophone ! So it’s not the least of the merits we can credit Dylan with, as we can many of the early idols of English pop, who all worshipped the likes of Presley, Cochran, Berry, Holly and Jerry Lee, but didn’t forget to bring their other heroes lurking in the shadows to our attention too – Sonny Boy Williamson, for example (the real one, n° 1, John Lee Curtis d. 1948 and the fake, n° 2, Rice Miller), Bill Jazz Gillum, Howlin’ Wolf, Peg Leg Sam, Sonny Terry, Walter Horton, Slim Harpo, Jimmy Reed, Little Walter, Junior Wells, James Cotton…