Rajab Suleiman & Kithara

Biography Rajab Suleiman & Kithara

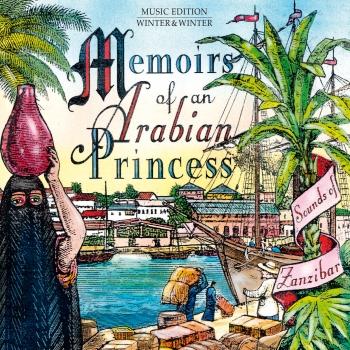

Zanzibar — comprising the islands of Unguja and Pemba and a few smaller islets just off the East African coast — is one of the centers of what is generally called Swahili culture, an Islamic urban culture molded by trade winds and contacts across the Indian Ocean. {Seyyid Said, Sultan of Oman and Zanzibar transferred his court to Zanzibar in the early 19th century and Zanzibar became the most important commercial entrepot for the East African trade in the course of the century. Zanzibar became a British Protectorate in 1890. In January 1964, just after independence, a revolution toppled the Sultan. In April of the same year, Zanzibar joined Tanganyika to become part of the United Republic of Tanzania.}

This culture flowered in the towns along the East African Coast at least since the 10th Century AD, communication across the sea, to Arabia, India and beyond, being assured by the dhow, the characteristic sailing vessel of the Indian Ocean. Until today the Zanzibari orient their lives more across the ocean and to the Islamic world rather than to the African mainland or the West, an outlook that is also very much apparent in the Islands' music and song.

The characteristic sound, defining the islands' aural landscape, is taarab music: traditionally in Zanzibar a lush sound produced by a variety of Oriental, African and Western instruments. In Swahili taarab describes the style of music as well as the occasion of performance; etymologically it is linked to the Arabic tariba, to be moved or agitated by playing or listening to the sound of music. The traditional setting for the live performance of taarab is primarily at weddings, with special concert performances on the occasion of Islamic holidays like Idd-el-Fitr.

Initially the orchestral sound of Zanzibari taarab had come to prominence in the wake of the popularity of Egyptian films, starring famous singers or composers like Umm Kulthum or Mohamed Abdel-Wahhab. However the Zanzibari orchestras produce a much sweeter sound, due to the more melodious Swahili language vocals and also the input of locally based African tunes. The names that came to incarnate this sound of Zanzibar are Ikhwani Safaa {Zanzibar’s oldest music club} and Culture Musical Club, the most popular orchestra leading up to the early 2000s. Society as a whole and fashions changed at a rapid pace in the past twenty years: A wave of so-called modern taarab has swapped over from the mainland and acoustic taarab has lost in popularity. The two big name clubs are all but dying, yet their legacy is alive.

Kithara was formed in 2011 by Rajab Suleiman and some younger members of the Culture Musical Club. „New times demand new structures to advance artistic goals“, he says. Feeling that their creativity was held up by the traditional club structure they branched out on their own.

Rajab has advanced his qanun playing studying repertoire from the instruments classical Arabic and Ottoman roots, branching out to include jazz or classical music. In building up a repertoire for the group, they have turned to the inspiration of Zanzibar’s many traditional ngoma dances, trying to marry the infectious rhythms and melodies to the groups regular taarab instruments that besides qanun, include ‘ud, violin, accordion, double bass and small percussion. Just recently up-and-coming new star Saada Nassor joined the group and in a short while has become the Islands’ most talked about new singer.

Kithara’s cherished male guest singer is Makame Faki, one of the doyens of Zanzibari taarab, having been a featured singer with Culture Musical Club for almost forty years.

Makame Faki also leads the Islands’ most in-demand kidumbak group Sina Chuki. Kidumbak is one of Zanzibar’s major wedding entertainments in the lower class areas of Zanzibar town and the rural areas of Zanzibar and Pemba. As a style kidumbak is somehow linked to taarab and its songs, yet it is per-formed with a reduced line-up of just one violin, vidumbaki {two small clay drums that give the style its name}, sanduku {tea-chest bass} and cherewa {maracas}. In contrast to taarab where the audience is traditionally seated, kidumbak is basically a dance-centered music, which integrates the female wedding audience as singers and chorus as well.

Qasida is an Arabic form of poetry dating back to pre-Islamic days. On the predominantly Islamic East African coast qasida has become an independent, Swahili-language form, which from the African context also draws melodic and polyrhythmic elements. The vocals of a lead singer are first picked up by a chorus. The singers are then joined by a set of up to ten tuned frame drums. Initially the chorus just sits, yet as the rhythm develops, increasingly complex wave-like movements develop where the participants straighten up yet always remain on their knees.

Tarbiyya Islamiyya is a madrasa founded by teenagers from Mfereji Wawima, a suburb of Zanzibar City. Aman Ussi and friends founded the first Islamic school for the children of the neighborhood, but soon discovered their own talent as composers and lyricists — and that of their students

as a singer and choreographers. Meanwhile, the group has become one of the leading ensembles in Zanzibar, being invited to perform maulid during various social events such as weddings, birth celebrations and circumcision ceremonies. A maulidi is a performance celebrating the birth and life of the Prophet Muhammad.

The Mtendeni Maulid Ensemble performs a visually and acoustically striking style of Sufi religious devotion called Maulidi ya Homu. The form has roots in the ancient Arab world, but today survives only in Zanzibar. Maulidi ya Homu is associated with the tariqa, Sufi order or brotherhood, founded by Ahmad al-Rifa’i. The Rifa’iyya originating in Egypt has spread over the Near and Middle East, but also as far as Indonesia, the Comoros, and Zanzibar. The form of Maulidi ya Homu performed today is thought to have originated from Iraq and came to the island around 1800. Over time the performance has become distinctly Zanzibari, blending local ngoma traditions with Sufi elements. Maulidi ya Homu is at once a musical, a religious, and a literary performance that draws on a rich heritage: A Sufi mystical tradition that has become amalgamated with Swahili aesthetical and cultural values.

Qasida are sung in both Arabic and Swahili, they are usually in praise of the Prophet Mohamed or extol the virtue of his life. Tarbiyya’s qasida here are „Ya Tawwabu Subhanallah” {Oh Ever-Returning, Glorified be Allah} and „Habibi Nabii Muhammad” {The Beloved Prophet Muhammad}. Mtendeni’s performances are much more improvised and usually string together pieces from various compositions. The sections here are „Shufaini” (Fear not) and „Khamsa arikanu” (Five Pillars).

Taarab is a repository of the old Swahili traditions of poetry. This poetry follows strict rules of syllables, lines and rhymes, the true meaning of songs often hidden under layers of metaphor and other tropes. Saada Nassor’s „Ondoa Hofu” asks a beloved to not be afraid to pronounce the truth about his or her feelings. Makame Faki’s „Aheri Zamani” laments the passing of an age. Kithara’s other songs are adaptations of ngoma, traditional dance songs. Ngoma songs usually string together choruses from various songs, the same is true of kidumbak songs, which are usually medleys or quotes from taarab songs, with catch-phrases from various genres thrown in the faster dance sections. (Werner Graebner)