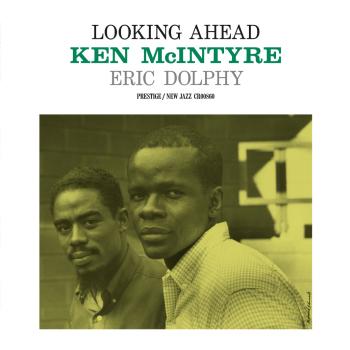

Ken McIntyre & Eric Dolphy

Biographie Ken McIntyre & Eric Dolphy

Makanda Ken McIntyre (1931-2001)

was among the group of innovative jazz musicians who emerged during the early 1960s. He was well schooled in the jazz conventions of the 1940s and 1950s, but he created a path of his own, in which the improvisational language and compositional structures extended in some different directions. Makanda’s music defied categorization. His playing was both “inside” and “outside.” He was comfortable in the “free jazz” idiom, for instance, but he considered the “avantgarde” label most inappropriate. Here he briefly explains his regard for Charlie Parker and the role that played in his musical development.

Makanda remained active and productive as a performer and composer until his passing in 2001. He also remained under-recognized throughout his lifetime, one reason being that much of his energy was devoted to his work as an educator.

The following biography is taken from the Makanda Ken McIntyre website. There is much more information about him on that site.

In the Wind“World-renowned multi-instrumentalist, composer, orchestrator and educator Makanda Ken McIntyre was a tireless musical innovator for nearly half a century, with 12 albums and more than 400 compositions and arrangements to his credit. His works include compositions for woodwind quartets, chamber ensembles, jazz bands, and full orchestra, as well as hundreds of lead sheets. He composed ballads, calypsos, bebop, avant-garde, and the blues.

“Makanda was known primarily for leading his own ensembles – performing on alto saxophone, flute, bass clarinet, oboe, and bassoon – and being proficient on more than 16 instruments, including bass, drums, and piano. His playing on all these instruments projected a highly energetic, celebratory life force.

“Makanda, whose given name was ‘Kenneth Arthur McIntyre,’ was born on September 7, 1931 in Boston, Massachusetts. His parents, who were from Jamaica, raised him in the South End, a largely West Indian area. He picked up his first saxophone at the late age of 19 after being inspired by Charlie Parker. He made up for lost time through tireless practice and discipline.

“After serving two years in the Army, Makanda earned his bachelors in Music Composition from the Boston Conservatory of Music in 1958, with a certificate in flute performance; a Masters in Music Composition from Boston Conservatory in 1959. He took an Ed.D. in Curriculum Design from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst in 1975.

“His tremendous work ethic was evident throughout his life and his teachings. He committed himself to inspiring all people about music and believed in the unlimited potential of every student. Makanda taught extensively in the New York City schools and also served on the faculties of Central State University, Wesleyan University, Fordham University, Smith College, and the New School University Jazz and Contemporary Music Department. In 1971, he began a 24-year tenure at the State University of New York/College at Old Westbury. At Old Westbury, he founded and chaired the American Music, Dance, and Theater Program, which was one of the country’s first departments dedicated to the arts in the African American tradition. Makanda designed and taught more than 10 courses in instrumental music, arranging, history, theory, and composition. He retired as a professor emeritus from Old Westbury in 1995.

“In 1983, Makanda founded the Contemporary African American Music Organization (CAAMO) to promote free expression and continuing education in music and the performing arts with African American origins. CAAMO held more than 250 performances and educational workshops throughout the New York area. The CAAMO orchestra performed in many venues, including Carnegie Recital Hall, throughout the 80’s.

Makanda alto“Makanda performed to great acclaim worldwide. He toured with Beaver Harris and the 360 Degree Music Experience, with Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra, and appeared on Cecil Taylor’s groundbreaking album, Unit Structures. In he early 90’s he was artist-in-residence in Bolivia. In 1998, he served as a jazz ambassador to the Middle East under the auspices of the Kennedy Center and the United States Information Agency.

“He had the privilege to perform and record with such artists as Nat Adderly, Walter Bishop, Jr., Joanne Brackeen, Jaki Byard, Ron Carter, Richard Davis, Eric Dolphy, Charlie Haden, Craig Harris, Sam Jones, David Murray, Charli Persip, Ben Riley, Warren Smith, Andrei Strobert, Arthur Taylor, and Reggie Workman.

“It was in the early 90’s that he changed his name to Makanda Ken McIntyre. While performing in Zimbabwe, a stranger handed him a piece of paper on which was written, “Makanda,” which means “many skins” in the Ndebele language and “many heads” in Shona.

“Makanda was devoted to his family, and named many tunes after them, including his mother, Blanche, his father, Arthur Augustus, his sister, Eileen Mercedes (‘Puunti’), his first wife, Charlotte (‘Charshee’), his sons Kaijee and Kheil, and his second wife, Joy. His song titles reflect a deep pride in his Jamaican heritage, his commitment to African American struggles, his spiritual nature, and his love of good food!

Eric Dolphy

was a true original with his own distinctive styles on alto, flute, and bass clarinet. His music fell into the “avant-garde” category yet he did not discard chordal improvisation altogether (although the relationship of his notes to the chords was often pretty abstract). While most of the other “free jazz” players sounded very serious in their playing, Dolphy’s solos often came across as ecstatic and exuberant. His improvisations utilized very wide intervals, a variety of nonmusical speechlike sounds, and its own logic. Although the alto was his main axe, Dolphy was the first flutist to move beyond bop (influencing James Newton) and he largely introduced the bass clarinet to jazz as a solo instrument. He was also one of the first (after Coleman Hawkins) to record unaccompanied horn solos, preceding Anthony Braxton by five years.

Eric Dolphy first recorded while with Roy Porter & His Orchestra (1948-1950) in Los Angeles, he was in the Army for two years, and he then played in obscurity in L.A. until he joined the Chico Hamilton Quintet in 1958. In 1959 he settled in New York and was soon a member of the Charles Mingus Quartet. By 1960 Dolphy was recording regularly as a leader for Prestige and gaining attention for his work with Mingus, but throughout his short career he had difficulty gaining steady work due to his very advanced style. Dolphy recorded quite a bit during 1960-1961, including three albums cut at the Five Spot while with trumpeter Booker Little, Free Jazz with Ornette Coleman, sessions with Max Roach, and some European dates.

Late in 1961 Dolphy was part of the John Coltrane Quintet; their engagement at the Village Vanguard caused conservative critics to try to smear them as playing “anti-jazz” due to the lengthy and very free solos. During 1962-1963 Dolphy played third stream music with Gunther Schuller and Orchestra U.S.A., and gigged all too rarely with his own group. In 1964 he recorded his classic Out to Lunch for Blue Note and traveled to Europe with the Charles Mingus Sextet (which was arguably the bassist’s most exciting band, as shown on The Great Concert of Charles Mingus). After he chose to stay in Europe, Dolphy had a few gigs but then died suddenly from a diabetic coma at the age of 36, a major loss.

Virtually all of Eric Dolphy’s recordings are in print, including a nine-CD box set of all of his Prestige sessions. In addition, Dolphy can be seen on film with John Coltrane (included on The Coltrane Legacy) and with Mingus from 1964 on a video released by Shanachie. (Scott Yanow, AMG)