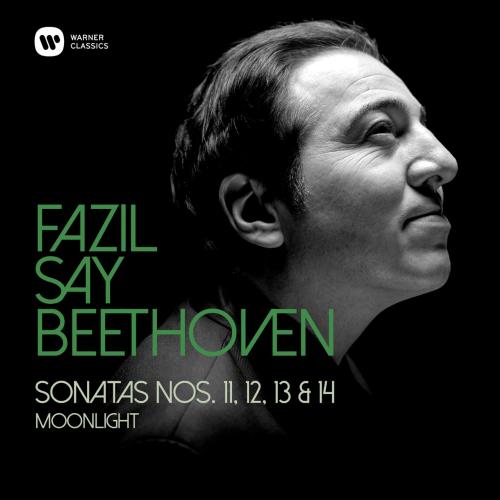

Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos 11, 12, 13 & 14, "Moonlight" Fazil Say

Album info

Album-Release:

2020

HRA-Release:

17.01.2020

Label: Warner Classics

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Instrumental

Artist: Fazil Say

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

Album including Album cover

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 - 1827): Piano Sonata No. 11 in B-Flat Major, Op. 22:

- 1 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 11 in B-Flat Major, Op. 22: I. Allegro con brio 07:31

- 2 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 11 in B-Flat Major, Op. 22: II. Adagio con molto espressione 07:31

- 3 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 11 in B-Flat Major, Op. 22: III. Menuetto 03:27

- 4 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 11 in B-Flat Major, Op. 22: IV. Rondo (Allegretto) 05:53

- Piano Sonata No. 12 in A-Flat Major, Op. 26, "Funeral March":

- 5 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 12 in A-Flat Major, Op. 26, "Funeral March": I. Andante con variazioni (Tema) 01:09

- 6 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 12 in A-Flat Major, Op. 26, "Funeral March": I. Andante con variazioni - Variation 1 01:10

- 7 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 12 in A-Flat Major, Op. 26, "Funeral March": I. Andante con variazioni - Variation 2 00:49

- 8 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 12 in A-Flat Major, Op. 26, "Funeral March": I. Andante con variazioni - Variation 3 00:55

- 9 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 12 in A-Flat Major, Op. 26, "Funeral March": I. Andante con variazioni - Variation 4 00:46

- 10 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 12 in A-Flat Major, Op. 26, "Funeral March": I. Andante con variazioni - Variation 5 01:23

- 11 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 12 in A-Flat Major, Op. 26, "Funeral March": II. Scherzo (Allegro molto) - Trio 02:55

- 12 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 12 in A-Flat Major, Op. 26, "Funeral March": III. Marcia funebre sulla morte d'un eroe (Maestoso andante) 07:25

- 13 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 12 in A-Flat Major, Op. 26, "Funeral March": IV. Allegro 02:52

- Piano Sonata No. 13 in E-Flat Major, Op. 27 No. 1, "Quasi una fantasia":

- 14 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 13 in E-Flat Major, Op. 27 No. 1, "Quasi una fantasia": I. Andante - Allegro 04:07

- 15 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 13 in E-Flat Major, Op. 27 No. 1, "Quasi una fantasia": II. Allegro molto e vivace 01:54

- 16 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 13 in E-Flat Major, Op. 27 No. 1, "Quasi una fantasia": III. Adagio con espressione 03:21

- 17 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 13 in E-Flat Major, Op. 27 No. 1, "Quasi una fantasia": IV. Allegro vivace 05:57

- Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 27 No. 2, "Moonlight":

- 18 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 27 No. 2, "Moonlight": I. Adagio sostenuto 07:16

- 19 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 27 No. 2, "Moonlight": II. Allegretto 01:53

- 20 Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 27 No. 2, "Moonlight": III. Presto agitato 07:02

Info for Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos 11, 12, 13 & 14, "Moonlight"

Marking Beethoven’s 250th birthday in a suitably heroic fashion, Fazıl Say has recorded Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos 11, 12, 13 & 14, Moonlight. He sees the sonatas as “a sacred text for musicians” and Beethoven as “A revolutionary composer starting to create music 50 to 100 years ahead of its time,” adding that: “When we interpret a composer’s work, we need to remain faithful to it. In other words, we need to feel like a composer. Compositions should be interpreted with the same freshness as a completely new piece of music that has just been created.”

“To date I have recorded 40 albums and composed 80 works. I have given around 3,000 concerts in various countries around the world. In the wake of all that I’d developed a desire to go beyond these achievements and do some of the very sincerest work I was capable of. That was how these recordings came about.

“There was an interesting new development during this recording process, in that I approached the playing with the mindset of a composer rather than that of a performer. When we interpret a composer’s work, we need to remain faithful to it. In other words, we need to feel like a composer. Compositions should be interpreted with the same freshness as a completely new piece of music that has just been created. To achieve this, we need to have a sense of what the composer imagined.”

“Two important imaginary creations”

“During my two years working on Beethoven, I came up with two important imaginary creations. The first was the ‘Fazıl Say Beethoven Orchestra’. I wanted to experience every piano sonata as though it were a symphony, to hear every sonata and every note in my mind, as though listening to an orchestra. I had imaginary rehearsals with this imaginary orchestra. Sometimes this imaginary scene was presided over by a conservative conductor, or one who was a manic Beethoven enthusiast; these imaginary rehearsals could be led by a wild Karajan or a sedate Furtwangler. They all directed my orchestra. We always held four-hour dress rehearsals for each sonata.

“I took another, even more fantastical approach. I played the sonatas to an ‘imaginary Beethoven’, who sat next to me, brimming with boundless energy and musical spirit. The imaginary Beethoven showed me his music, sometimes soothing me, sometimes wrestling with the dissatisfaction in my mind. This was the hardest and most unforgiving stage.

“Inside this imaginary world, I felt a need to prove myself. These imaginings ended with the start of recording in May 2017, and when sessions came to a close in May 2019, a strange weight lifted from me. I felt like I was in a huge void.”

“I devised my own personal leitmotifs.”

“Music should relate something, and the person relating it should make this narrative as clear as possible … This makes it important to assign names to melodies, to develop a way of working in which the performer devises leitmotifs. In this way it is possible to distance your thoughts from the mathematics of the text and instead to dramatise it.

“I devised my own personal leitmotifs for every theme of every sonata. For example, I came up with the ‘old man’ leitmotif for the heaviest section of the ‘Pastoral’ Sonata, the ‘distant drums of approaching warships’ leitmotif in the ‘Waldstein’, the ‘hopeless love’ leitmotif in Op.109, the ‘hope’ or ‘rebellion’ leitmotif in the ‘Appassionata’, and so on. I also gave names to some of the nameless sonatas, as I did when recording the Mozart cycle.

“A revolutionary composer starting to create music 50 to 100 years ahead of its time.”

“Together with Beethoven’s extraordinary mastery of all piano techniques, those who interpret his music must also take into account the things he did instinctively as a pianist. I want to hear Beethoven in the music.

“The works of Beethoven’s later period contain momentous steps towards Brahms, Wagner, Schumann and the composers of later generations. This is evident not just in the harmonic aspects and atmosphere of the works, but also in his voicing for the piano, which gradually takes on a more orchestral texture. I think the timbre of his last six sonatas has a very different tone to his previous ones. In fact, we can follow this development from the ‘Appassionata’ Sonata onwards. In my mind, it’s an orchestra that’s playing there. Particularly in the ‘Hammerklavier’ Sonata we can see a Beethoven making musical inroads into future eras, a revolutionary composer starting to create music 50 to 100 years ahead of its time.

“Music should be new every time it’s played. Each time a piece is performed, it should feel as though it has just been written. What matters is what we are saying and which feelings we convey to the human race. No one should say, ‘Beethoven played it like this, and everything else is wrong’. Beethoven would never have said that. Different interpretations are a composer’s delight.

Fazil Say, piano

Fazil Say

When the German composer Aribert Reimann discovered the 16-year-old Fazıl Say’s fast-developing artistry on a trip to the latter’s hometown of Ankara, Turkey, he exclaimed to the American pianist David Levine: “You absolutely must hear him – this boy plays like a devil.” Say had his first piano lessons from Mithat Fenmen, who had himself studied with Alfred Cortot in Paris. Perhaps sensing how talented his pupil was, Fenmen asked the boy to improvise every day on themes to do with his daily life before going on to complete his essential piano exercises and studies. This contact with free creative processes and forms is seen as the source of the immense improvisatory talent and the aesthetic outlook that have made Fazıl Say the pianist and composer he is today.

From 1987 onwards, Fazıl Say fine-tuned his skills as a classical pianist with David Levine, first at the Musikhochschule Robert Schumann in Düsseldorf and later in Berlin. This formed the aesthetic basis for his Mozart and Schubert interpretations, in particular, leading to victory at the Young Concert Artists International competition in New York in 1994. Since then he has played with all of the renowned American and European orchestras and numerous leading conductors, building up a multifaceted repertoire ranging from Bach, through the Viennese Classics (Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven) and the Romantics, right up to contemporary music, including his own piano compositions.

He has been commissioned to write music for, among others, the Salzburg Festival, the WDR, the Dortmund Konzerthaus and the Schleswig-Holstein and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern festivals. His work includes compositions for solo keyboard and chamber music, as well as solo concertos and large-scale orchestral works, such as the 2011 Clarinet Concerto for Sabine Meyer inspired by the life and work of the Persian poet Omar Khayyam.

Say is a passionate advocate of music as a path to social change, in his native Turkey and beyond. “I strongly believe that art and music will form a bridge between Western and Eastern cultures, blending and transforming these cultures,” he stated in a speech for the 38th Congress of the International Federation of Human Rights in Istanbul, 2013.

This album contains no booklet.