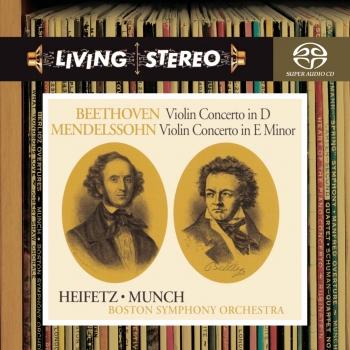

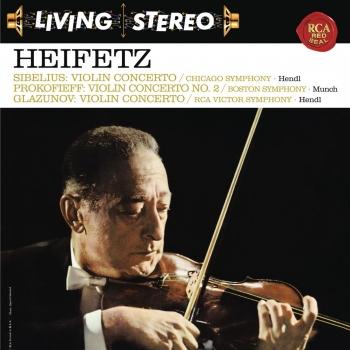

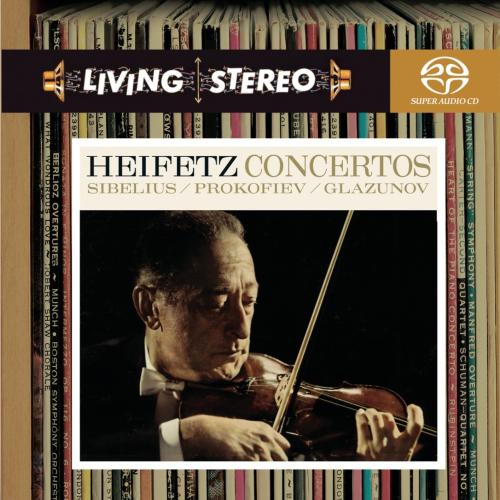

Sibelius / Prokofiev / Glazunov: Violin Concertos Jascha Heifetz

Album info

Album-Release:

1963

HRA-Release:

31.03.2015

Label: Living Stereo

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Concertos

Artist: Jascha Heifetz

Composer: Jean Sibelius (1865-1957), Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953), Alexander Glazunov (1865-1936)

Album including Album cover Booklet (PDF)

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- Jean Sibelius (1865–1957): Violin Concerto in D Minor, Op. 47

- 1 I. Allegro moderato 13:37

- 2 II. Adagio di molto 06:18

- 3 III. Allegro, ma non tanto 06:48

- Sergei Prokofjew (1891–1953): Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor, Op. 63

- 4 I. Allegro moderato 09:02

- 5 II. Andante assai 07:59

- 6 III. Allegro ben marcato 06:11

- Alexander Glasunow (1865–1936): Violin Concerto in A Minor, Op. 82

- 7 I. Moderato 03:59

- 8 II. Andante sostenuto 03:24

- 9 III. Più animato 06:04

- 10 IV. Allegro 05:29

Info for Sibelius / Prokofiev / Glazunov: Violin Concertos

This Heifetz recording of this Prokofiev concerto is one of the finest performances and recordings of anything ever done, and in this splendid new digital reincarnation critical sonic details come through with added clarity, e.g., the pp bass drum notes. Heifetz and Munch attain the Haydnesque almost robot-like andante assai accompaniment in the slow movement contrasting vividly with the melting sweetness of the violin line. Most importantly, in all of these re-mastered Heifetz recordings the violin tone is greatly enriched to the benefit of Heifetz’s reputation. Surprisingly, for an artist who recorded as much as he did, microphones were not kind to Heifetz’s tone.* On many commercially released recordings, Heifetz sounds astringent, gritty, sour, even false; but here we hear what he really sounded like and the real beauty and complexity of his tone is made clear on recording at last for those of us who could never hear him play live up close.

Rozhdestvensky and Perlman do a beautiful job with this work also, warmer, sweeter, more rhapsodic, a smoother surface throughout. Timings on the first and second movement are 12% longer. Some will like the performance better although the recording quality, while excellent for CD, cannot compare with the SACD.

In the Sibelius Concerto Heifetz is competing with himself; his 1935 recording with Beecham remains a monument, a standard not yet surpassed; however, that primitive recording distorts the overall orchestral sound as well as leaving many details inaudible. Real connoisseurs will need both recordings to truly appreciate Heifetz’ accomplishment. Wisely not attempting to better Heifetz, other violinists move in other directions. Mutter and Previn give us hair-tearing, tear-jerking, foot-stomping gypsy passion. Eidus goes them even one further; his first two movements are gut-wrenching, heart-rending, but he actually can’t manage the rapid leaps and double-stops in the finale. Kavakos gives us the 'original' 1903 version, as much like the familiar 1905 version as Mussorgsky’s original Boris is like the Rimsky-Korsakov version. When you think you’ve heard everything in this concerto, then listen to the earlier version, hear Sibelius’ creative mind in action, and thus deepen your understanding of the artistic decisions he eventually made in comparison with his original inspirations. Kraggerud and Engeset give a very capable, very individual reading on a surround sound DVD-Audio. Another worthy version I have enjoyed is by Tossy Spivakovsky and Tauno Hannikainen on Everest, and classic account by Julian Sitkovetsky (father of Dimitri) also deserves mention.

In the notes to the Perlman recording, the annotator* says that the Violin Concerto is '... generally regarded as Glazunov’s most brilliant and effective composition.' That may have been a true statement in 1989, however no one who has heard a good recording of the Fifth Symphony (Polyansky, or Fedoseyev) or the First Symphony (Järvi) could possibly agree with it. It is interesting that some passages clearly inspired Prokofiev in his Second Violin Concerto. Although sensationally popular in Russia, Glazunov is only now becoming known in the West. The Violin Concerto has been familiar for a long time, but we have many treasures yet to discover, and when that has occurred, the Violin Concerto will probably move down a few notches in the list.

In the Glazunov Concerto the 'RCA Victor Symphony Orchestra' would likely be either the 20th Century Fox or MGM Studio orchestra, or maybe members of both, first-rate musician friends of Heifetz’s, come just down the street from the studios to the hall. In spite of the exceptional recording quality, Heifetz’ emotionality here leaves me relatively unaffected; it seems artificial, calculated; but, be that as it may, Heifetz’ performance of the cadenza is a stunning musical achievement you won’t want to miss hearing. Perlman gives us authentic emotion and drama. Fischer, on a Pentatone surround sound SACD, gives us a clear, straightforward but sensitive reading without sentimentality and makes the dramatic structure of the work more evident. Overall, I prefer both Perlman and Fischer to Heifetz in this concerto.

However, the recording of the accompaniments in all cases is clearly superior on the RCA to the others, even to the newer surround sound recordings. You will hear new details in the orchestral parts. With these rich detailed recordings it is easy enough to generate convincing rear channel information from a quality surround sound processor.

*In contrast to Louis Kaufman, who recorded most working days of his career, and sounded extremely good over the microphone. In person he may not have sounded so good.“ (Paul Shoemaker, MusicWeb International) **Colin Kolbert

Jascha Heifetz, violin

Boston Symphony Orchestra (on tracks: 4 to 6)

Charles Munch, conductor (on tracks: 4 to 6)

Chicago Symphony Orchestra (on tracks: 1 to 3)

RCA Victor Symphony Orchestra (on tracks: 7 to 10)

Walter Hendl, conductor (on tracks: 1 to 3, 7 to 10)

Engineered by John Crawford, John Norman, Leslie Chase, Lewis Layton

Produced by John Pfeiffer

Jascha Heifetz

Jascha Heifetz’s celebrated position as one of the greatest violinists of the twentieth century seems unassailable. Along with that of Fritz Kreisler, his name is associated with the evolution of the instrument’s technique and style in the first half of the century. Famed though Heifetz was for his extraordinary reliability and dazzling technique, his reputation nonetheless suffered slightly from intimations that he was a rather uninvolved player. Early in his career, he attended a gathering of several notable players in a private house in Berlin where he gave a performance of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto with Kreisler at the piano; Kreisler commented to the other violinists present: ‘We may as well break our fiddles across our knees.’ Upon Heifetz’s London début in 1920 at the Queen’s Hall (having already sold 70,000 recordings in the UK) Bernard Shaw wrote to him, remarking: ‘Your recital has filled me and my wife with anxiety. If you provoke a jealous God by playing with such superhuman perfection, you will die young. I earnestly advise you to play something badly every night before going to bed, instead of saying your prayers. No mortal should presume to play so faultlessly.’

After initial training by his father, Heifetz attended the Vilna School of Music (under the direction of Elias Malkin, a former pupil of Leopold Auer). Later he went to Auer himself as the youngest member of his class in St Petersburg and remains one of Auer’s best-known pupils.

Heifetz’s own teaching engagements were both exacting and sporadic. Erick Friedman became his first regular pupil in 1957, cancelling a large number of concert engagements to take up intensive study with him which was given free of charge. Heifetz undoubtedly transformed Friedman’s playing and moulded him in his own image in terms of interpretation (he reputedly never imposed his own technical methods upon others), eventually paying him the greatest of compliments by inviting him to record Bach’s Double Violin Concerto (the only recording of the work made by Heifetz in which he is partnered by another violinist, Heifetz famously having otherwise recorded both parts himself ). From 1962–1972 he was Professor of Violin at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Well known for being methodical in his preparation, Heifetz was noted for remaining consistent in his interpretation (rather in the manner of Rachmaninov as a pianist) as opposed to the older tendency towards spontaneity in each performance. In this sense his approach can be seen as the antithesis to Joachim’s (although via Auer he had a linked pedagogic lineage). He recorded remarkably widely, his first commercial discs being made in 1917. Early accounts of Heifetz’s playing whilst still in St Petersburg c.1910 reveal that he had already acquired something of his distinctively penetrating and devastatingly accurate tone. His recordings show amazing technique, as well as a highly influential style of playing: accurate to the letter of the musical score, sweetened by an intense and (some might argue) rather too regular vibrato. Claims for his modernity can however be overstated. His use of portamento throughout his career (uniquely linked to a fast accentual vibrato which came to be termed the ‘Heifetz slide’) sounds unfamiliar to today’s ears even though, as in the case of recordings by the actor John Gielgud, it is remarkable how little his tone varied throughout his life. Many readers will find it surprising that Heifetz played on gut strings throughout his career, the sound he desired being achieved with a silver-wound gut G, plain gut D and A, and a ‘Goldbrokat’ steel E.

Heifetz’s discography is so large it is hard to do it justice here in so small a space. This said, his playing has a notable consistency that makes generalisation rather less problematic. His distinctive style – the tautness of sound, with regular but generally well-controlled vibrato; his frequent employment of a distinctive portamento, quite different from those employed by violinists of the nineteenth century – enlivens many cantabile passages, and his peerless agility and intonation are remarkable even by today’s standards. Much of this sound, however, admits relatively little variation, so that in truth one is hearing Heifetz first and the composition as a mere vehicle. This works better in some contexts than others. The Bach and Mozart concertos selected here (including a famous 1946 recording of Bach’s Double Violin Concerto with Heifetz playing both parts) seem comparatively un-nuanced to our modern ears. His 1951 performance of Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 5 is typical in its rather steely character, although the finale is taken in a poised and stately fashion. The 1939 and 1956 recordings of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto show a little change in style: the earlier recording is fastidious but tonally subtle; the later employs a harder, perhaps more brash sound. The extent to which this perception is the result of changing recording technology or Heifetz’s own advancing years is debatable (similar traits mar later Elman discs as well, but to a much greater extent). For me, though, Heifetz’s recorded performances of Franck’s Violin Sonata (1937) and Walton’s Violin Concerto (1941) are masterly. Here his sound, (which one might describe as that of an iron fist in a velvet glove) seems more appropriate; from the tough yet mysterious opening of the Walton to the laconic performance of Franck’s first movement it is counterpoised throughout by an electric, if tightly controlled, sense of excitement.

Booklet for Sibelius / Prokofiev / Glazunov: Violin Concertos