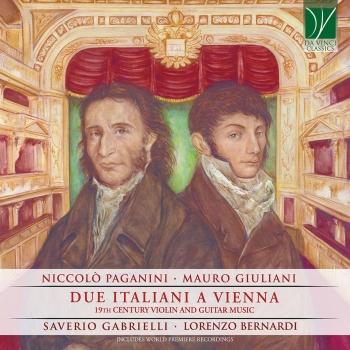

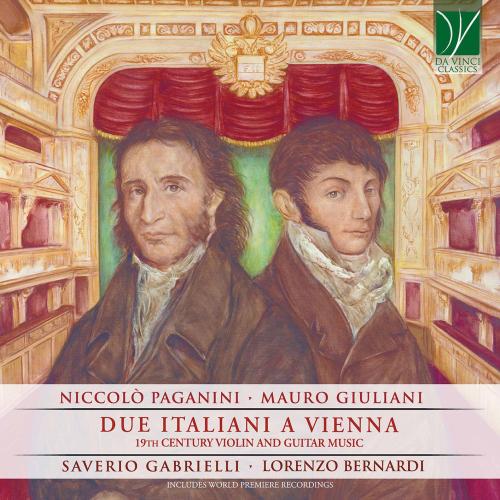

Giuliani, Paganini: Due Italiani a Vienna Saverio Gabrielli & Lorenzo Bernardi

Album info

Album-Release:

2022

HRA-Release:

22.04.2022

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Instrumental

Artist: Saverio Gabrielli & Lorenzo Bernardi

Composer: Mauro Giuliani (1781-1829), Niccolò Paganini (1782-1840), Louis Spohr (1784-1859)

Album including Album cover

- Niccolò Paganini (1782 - 1840): Sonata No. 1 in LA Minore dal “centone di Sonate” M.S. 112:

- 1 Paganini: Sonata No. 1 in LA Minore dal “centone di Sonate” M.S. 112: Introduzione - Larghetto / Tempo di marcia - Allegro maestoso 05:15

- 2 Paganini: Sonata No. 1 in LA Minore dal “centone di Sonate” M.S. 112: Rondoncino - Allegro 04:01

- Mauro Giuliani (1781 – 8 May 1829): Serenata Op. 127:

- 3 Giuliani: Serenata Op. 127: Maestoso 03:26

- 4 Giuliani: Serenata Op. 127: Minuetto - Allegretto - Trio 04:35

- 5 Giuliani: Serenata Op. 127: Tema - Andantino Mosso 01:44

- 6 Giuliani: Serenata Op. 127: Variazione I - Più Mosso 01:18

- 7 Giuliani: Serenata Op. 127: Variazione Ii - Più Lento 02:58

- 8 Giuliani: Serenata Op. 127: Variazione Iii - Primo Tempo 01:53

- 9 Giuliani: Serenata Op. 127: Rondò - Allegro 03:29

- Niccolò Paganini: onata Concertata M.S. 2:

- 10 Paganini: Sonata Concertata M.S. 2: Allegro spiritoso 07:58

- 11 Paganini: Sonata Concertata M.S. 2: Adagio assai espressivo 03:36

- 12 Paganini: Sonata Concertata M.S. 2: Rondeau 02:46

- Mauro Giuliani (): Gran Duetto Concertante Op. 52:

- 13 Giuliani: Gran Duetto Concertante Op. 52: Andante sostenuto 04:08

- 14 Giuliani: Gran Duetto Concertante Op. 52: Menuetto - Allegro vivace 04:47

- 15 Giuliani: Gran Duetto Concertante Op. 52: Rondò militare - Allegretto 07:37

- Louis Spohr (1784 - 1859): Grande Duo Op. 11:

- 16 Spohr: Grande Duo Op. 11: Allegro moderato (Transcribed by Anton Diabelli) 10:13

- 17 Spohr: Grande Duo Op. 11: Adagio (Transcribed by Anton Diabelli) 05:28

- 18 Spohr: Grande Duo Op. 11: Rondò (Transcribed by Anton Diabelli) 08:20

Info for Giuliani, Paganini: Due Italiani a Vienna

Those who still think of Wagner’s Tristan as quintessentially erotic music should definitely reconsider: in the list drawn by The Most Erotic Classical Music of All Time, an album with a provocative cover featuring a woman’s derriere and suspenders, in good company with an obvious Bolero and a punctual isottesque finale and a less-obvious Moonlight Sonata or a Good Friday Spell (all by the German from Leipzig), one finds the Centone di Sonate for violin and guitar by Niccolò Paganini (Genoa 1782 – Nice 1840) and precisely with the opening movement of the Sonata in A minor placed in the opening of the present collection.

A very bizarre choice indeed, possibly ascribable to the legendary (i.e., completely made-up) familiarity the Genoan composer had with the devil and women? Maybe. But here, we would like to speculate a more subtle reference to the communicative, ‘sensual’ and ‘sensory’ features of the repertoire where Paganini shows his prominent interest for guitar coupled with his beloved violin. The image of the divo assaulted by the very same shouting teenagers who surrounded The Beatles in the Sixties is supplanted by the modish and ‘chamber’ ritual of the same young lady who – in love with her musical idol and without posters, iPhones or iPads – is accompanied by the guitar with languid and falsely prudish wide eyes.

However, one would hurt the ethical-esthetic dignity of figures like Paganini or his peer Mauro Giuliani, his companion in this recording, if he should associate them with those hormonally unstable young ladies, enslaving their chamber (or so-called ‘secondary’) pages to a mere marketing diktat.

Eros does not necessarily correspond to the vulgarity of the aforementioned cover, nor is it synonymous with superficiality. Granted, these pages do indeed bleed vulgarity (from the Latin vulgus = people, crowd), but only in strict observance of the etymology that was rediscovered by Romanticism: ‘popular’ meant sincere, direct, recognizable, immediately understandable and gratifying. Just like the simple ringing of the triangle in the Rondo ‘La Campanella’, a genius intuition Paganini drew not by a treatise on composition, but by the streets of old Genoa, where the beggars – with the penetrating sound of rough triangles or rudimentary pieces of iron drew the attention of passers-by urging them to offer pious alms.

Even though these works by Paganini and Giuliani welcome the classic tradition of Alessandro Rolla’s duets (for violin and guitar, flute and violin, mandolins…), nevertheless they subvert their ‘pedantic’ didactic objective in light of Mazzini and Manzoni’s ‘social’ art. They are not meant for the prince’s son (who had to learn music according to etiquette), nor are they for the aristocratic cultural gatherings where scraps of pompous minuets always made an appearance. They are for the new audience the French Revolution gave birth to, who makes and listens to music on the streets, in the gardens and taverns, the very places one could turn to when looking for catchy melodies and unusual sounds. A world of Freiluftmusik or Tafelmusik which became globalized in Europe by the increase in mobility, but also by the itinerant virtuosos (naturally lead by Paganini) who still had a Viennese heart, the Empire’s capital striving to boast the international fame of Italians Niccolò and Mauro (Paganini for violin, Giuliani for guitar).

Despite the formally austere title, the pages in the Centone di Sonate are astonishing miniatures replayed through the frequent use of the Ritornello, a symbolic reiteration of pleasure. They are a series of specific figurations that can unexpectedly spark strong emotions due to their brevity: a sense of anxious anticipation (the extremely fast repeated notes at the beginning of Sonata n. 1) recalled ‘by surprise’ at the end; the pizzicato in minor key in the middle of an otherwise sparking trio, the heroic and martial March lead by the violin, with a guitar accompaniment, also in Sonata n. 1; the harsh martial traits of the Rondò militare in Mauro Giuliani’s Gran Duetto concertante op. 52; the conciseness and pathos of the second variation which take turns with more sprung rhythms as in Mauro Giuliani’s Rondò of the Serenata op. 127. All is narrated by a soloist who had to be charismatic, chased by the continuous, uniform and most of all reassuring accompaniment of the guitar, which nevertheless becomes the absolute deuteragonist in Mauro Giuliani’s op. 52. The very same happens in Paganini’s Sonata Concertata: here, the two instruments give life to a balanced dialogue where the features of unpredictability, joy and vivacity reveal themselves in the continuous intertwining melodic ‘chiasmi’ of the opening Allegro spiritoso and in the fast pacing at the end of the Allegretto con brio. Scherzando.

Paganini and Giuliani’s unprecedented care for an unknown audience that had to be ‘conquered’ emphasizes a melodic and rhythmical sensitivity which is fed by the present and welcomes dancing and themes and songs from the multifaceted reality of everyday life: sounds from theatres, folklore, the military world, the streets. A contamination of high culture which is prominent in the admission of Rondò and Marcia, Minuetto or Fandango, types of dance that inevitably allude to the body and ‘vulgar’ matter and are based on the predictable and reassuring principle of symmetrical alternation (4+4 bars) rather than on the infinite processes of the concept of development, which is called forth to back more complex and extended forms.

The combined action of two exceptional instrumentalists such as Paganini and Giuliani (the latter only one year older than the former) prompted the spread in the most refined environments of the unexpected coupling of guitars and violins: agile, sparkling and functional to the many festive occasions the new sociability demanded. But also marketable, so that it immediately became interesting to the publishing industry, which paid close attention to the genre’s profitable circulation both through new works and in transcriptions.

This is the theme of the last number in this anthology with prolific musician Anton Diabelli (who was the same age as Mauro Giuliani). Already and established composer of his own pieces for violin, guitar, guitar and piano and guitar and violin, he transcribes for violin and guitar an original string quartet penned by the ‘German Paganini’ Louis Spohr (1784-1859): the renowned Gande Duo op. 11.

Released in 1812-13 and recently republished by Fabio Rizza, the Duo now reaches its first discographic debut. The thin line that was still drawn in Luther’s times between ‘strict Protestants’ and ‘jolly Papists’ does not cease to reveal itself in the works of Spohr, an illustrious and virtuoso violinist and the representative of a German north that was less inclined to welcoming the intrusion of instinct and imagination (even though the musician briefly lived in Vienna between 1813-15). With the ghost of Bach looming over him (a matter of DNA!), Spohr’s quartets show an incessant interplay between their parts, the search for sound density rather than for extended singability or for the Italians’ unexpected flairs. The tendency to isolate the first violin with especially sparking virtuosities is a clear reference to the concert, with the author in the front row and the ‘entourage’ in the background. After all, Louis Spohr was the leading representative of the post-Congress of Vienna style termed Biedermeier: a way of making music that was markedly opened and backed to the point that it even challenged traditional ‘individualism’, a term which had been coined for the chronologically contemporary word ‘Romanticism’.

Therefore, in the face of an undoubtedly classical education, in his music Spohr often used complicated descriptive virtuosities. He demanded his performer to show a sober yet languid carrying; he provided accompaniments that were passionate and vibrant, and no longer restrained. In the intimate pages from the Leider, the quartets and the pieces for harp one finds sanctuaries of intense singability, as in the central Adagio of the present Grande Duo op. 11, whose incipit clearly bears reference to Don Ottavio’s aria Il mio Tesoro intanto taken from Mozart’s Don Giovanni.

However, the slow tempo’s singing often stands opposite to an enthralling final Rondò dominated from beginning to end by an incessant and aggressive dotted rhythm.

In Diabelli’s transposition a greater space is given to the guitar, which takes up the sections that were of the low strings. The intensity of the composer’s mental commitment, the idea of always representing German Kulture no matter what does not leave much space here to ‘vulgarity’ and the dancing body: this piece could have never been included in the top list from The Most Erotic Classical Music of All Time. And it would have been impossible to find Louis Spohr as a guest of the smoky tavern in the London suburbs where David Garrett aka Niccolò Paganini (in The Devil’s Violinist, directed by Bernard Rose in 2013) improvises on the theme of the ‘vulgar’ Carnival of Venice making the freckled androgynous Times journalist burn with desire…

Mauro Giuliani in Vienna by Cav. Nicola Giuliani, President and Founder of Casa Museo Giuliani

In the last few years the work, life and legacy of Mauro Giuliani have proven to be a shrine of information from which many researchers, biographers and musicologists have drawn in order to complete the human profile of the great proto-Romantic composer from Bisceglie, striving as they are to find the missing pieces of the puzzle in his work as a composer, concertist and in the publications he has been the subject of.

In Vienna, where he arrived in 1806, Mauro lived the most fruitful years in his compositional and concertist production. The stars of many musicians were shining in the Habsburg capital at the time: Spohr, Hummel, Moscheles, Mayseder. Mauro began meeting and spending time with them, especially as he shared the status of ‘emigrant’ with many of his colleagues.

It was in Vienna that Mauro prepared an event that would become memorable: the first performance of Concert op. 30, Giuliani’s work that it is more than others in the big repertoire.

In the capital he met Maria Anna Wiesenberger, also known as Nina, who would bear him three children. Accounts have always described him as a sociable man who was always ready with a joke, qualities he probably never lost even at difficult times. As a matter of fact, Nina died prematurely in 1817 and shortly after his youngest daughter Karolina passed away on March 25, 1818.

In Vienna, Mauro lived in the Singerstrasse near St. Stephen’s Cathedral in 1810 and at house number 939 in 1817, the same year in which he resumed his performances in the imposing hall of the Theater an der Wien and in his favourite Redoutensaal.

One of the main contacts Giuliani had in Vienna was Anton Diabelli, who apart from being an excellent musician also became one of Giuliani’s chief publishers after Artaria. In memory of their friendship, the Casa Museo Giuliani still holds an original letter penned by Michele Giuliani on April 25, 1825 and sent to Diabelli through their friend Antonio Spina, one of Mauro’s pupils.

After returning to Italy in 1819, the “Diario di Roma” from April 20, 1820 mentioned him as being in the Papal capital “coming from Vienna”. Mauro was to remain in Rome for well over three years until the summer of 1823.

A few years later, biographer Isnardi described the bond he formed in Rome with Rossini and Paganini, in what historian Giancarlo Conestabile termed the “musical triumvirate”. Conestabile mentions it in the Vita di Niccolò Paganini and says that while Rossini was working on Matilde di Shabran they often met at the composer’s Roman home, and “were always together with the great man from Pesaro, one playing the guitar, the other the violin. The two sublime talents of Italian art, that is Giuliani and Paganini”. Together they gave “such celebrated entertainment” whose scope Mauro probably didn’t even imagine.

His life ended in Naples, where he passed away at midnight on May 7, 1829. His children had the arduous task of following in the musical footsteps of a great Italian in Europe.

The place where this performance was recorded is especially interesting. The Theatre in Verona that owes its name to actress Adelaide Ristori (1822-1906). The Casa Museo Giuliani in Bisceglie still holds a letter the actress wrote to Mauro Giuliani, which bears witness to the important relationships and exchange of correspondence the Artist had.

Saverio Gabrielli, violin

Lorenzo Bernardi, classical guitar

Saverio Gabrielli

Born in Trento in 1990, he graduated in violin with full marks and honors at the Conservatory E. F. Dall' Abaco of Verona under the guidance of M° Alberto Martini. He continues his studies with M° Ilya Grubert at the Fondazione Musicale S.Cecilia in Portogruaro (VE) and then at the Conservatory of Amsterdam, obtaining in June 2016 the Bachelor of Music thanks to the scholarship won at the Fondazione Cassa Rurale of Trento as the best study project at European level. She participates in the Masterclasses of M° Pierre Amoyal, Nobuko Imai, Ida Haendel, Nina Beilina, Pavel Berman, Vera Beths, Liviu Prunaru, Wolfgang Schroeder and Malcolm Bilson. He has received numerous national and international awards, including the 1st prize at the European Music Competition in Moncalieri (TO), the 1st prize at the extraordinary edition of the Francesco Geminiani Prize in Verona and the 1st prize and scholarship at the competition organized by the Rotary Club of Verona for the best execution of the Violin Concerto No. 1 op. 19 by S. Prokofiev. He also won the 2nd prize at the national competition Città di Giussano (MO), the 2nd prize at the International Music Competition in Cortemilia (CN) and the 2nd prize at the International Competition of Young Musicians - Antonio Salieri Prize (VR). Active chamber musician, he performs for important concert societies such as Anima Festival (Cuneo), Estate Musicale Frentana (Chieti), Palermo Classica, Goethe Institut Amsterdam, Società Filarmonica Trento, Badia Musica, Robeco Festival Concertgebouw. In duo with the cellist Stefano Guarino, she is part of the strings that accompany every year the finalists of the Roberto Melini International Piano Competition. He also collaborates with various ensembles and orchestras including I Virtuosi Italiani, the Orchestra del Festival Internazionale di Brescia e Bergamo, the Orchestra Nazionale dei Conservatori, the Symphony Orchestra of the Conservatorium van Amsterdam, Philharmonia Orkest Amsterdam, Orchestra Regionale dei Conservatori del Veneto and the Piccola Orchestra Lumière. He takes part in renowned festivals such as Il Settembre dell' Accademia, Festival Ad lucem - contemporary art with Arvo Pärt, Musica e arte sacra with Antonella Ruggiero, Suona Francese, Pergolesi - Spontini, Cello Biennale Amsterdam with Mischa Maisky, Giovanni Sollima, Johannes Moser, Frans Helmerson and Colin Carr. He plays under the guidance of important conductors such as Corrado Rovaris, Gianluigi Gelmetti, Alessandro Cadario, Fabien Gabel, Ed Spaniaard, Paul Watkins, Dirk Vermeulen, Junichi Hirokami and Andrew Grams. He has collaborated with the Ensemble The String Soloists of the violinist Lisa Jacobs, with whom he recorded the violin concertos by Locatelli and Haydn for Cobra Records. He has performed and recorded in the most prestigious halls of Holland such as the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, Paleis Het Loo in Apeldoorn, Tivoli Vredenburg in Utrecht, De Harmonie in Leeuwarden, Stadsgehoorzaal in Leiden, Muziekgebouw in Eindhoven. In October 2018, he also received his trilingual master's degree in Musicology from the Free University of Bozen/Bolzano with top marks.

Lorenzo Bernardi

Born in Trento in 1994, he graduated from the F.A Bonporti Conservatory of Trento in 2015. He then continued his studies with Emanuele Buono at the Conservatorio L. Canepa in Sassari, earning a second-level Master's degree in solo performance with top marks. Thanks to a scholarship offered by the European Community, he further specialized at the Conservatorio Manuel Castillo in Seville, Spain, under the guidance of the internationally renowned teacher and guitarist Francisco Bernier. As a soloist, but also as a member of chamber groups and with orchestra, he regularly performs on national and international territory such as Spain, U.S.A, Costa Rica, Panama, Argentina, Chile, Bahrain, Japan, Vietnam, Indonesia, Korea and India. Lorenzo Bernardi is endorser Savarez Strings.

This album contains no booklet.