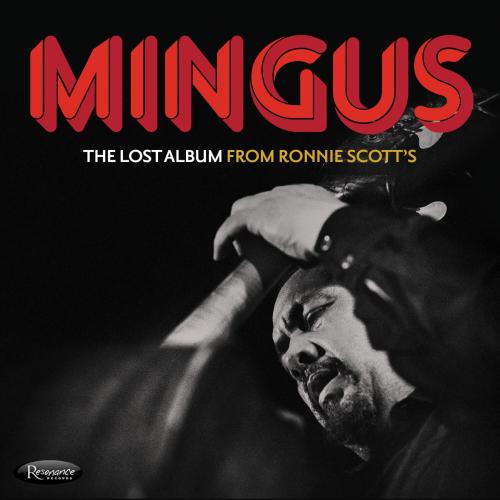

The Lost Album From Ronnie Scott's (Live) (Remastered) Charles Mingus

Album info

Album-Release:

1972

HRA-Release:

08.12.2025

Album including Album cover Booklet (PDF)

- 1 Introduction (Live) 01:01

- 2 Orange Was the Color of Her Dress (Then Silk Blues) (Live) 30:44

- 3 Noddin' Ya Head Blues (Live) 19:52

- 4 Mind-Readers' Convention in Milano (AKA Number 29) (Live) 29:57

- 5 Ko Ko (Theme) (Live) 00:44

- 6 Fables of Faubus (Live) 35:00

- 7 Pops (AKA When the Saints Go Marching In) (Live) 07:35

- 8 The Man Who Never Sleeps (Live) 18:33

- 9 Air Mail Special (Live) 02:02

Info for The Lost Album From Ronnie Scott's (Live) (Remastered)

The Lost Album from Ronnie Scott's is a never-before-released live recording of jazz icon Charles Mingus from Ronnie Scott's jazz club in London captured in August of 1972. Features a stellar band with alto saxophonist Charles McPherson, tenor saxophonist Bobby Jones, trumpeter Jon Faddis, pianist John Foster and drummer Roy Brooks.

In August 1972, the Charles Mingus Sextet had a two-week residency at Ronnie Scott’s. Now, almost 50 years after the residency and 100 years after Mingus was born, Resonance Records are releasing The Lost Album from Ronnie Scott’s – uncovered and remastered tapes.

These are not any old tapes scraped off the bottom of the archival barrel – these are high-quality live sets put down in a mobile recording truck on an eight-track with the intention of being released at the time.

The original planned release of the album never happened – Columbia Records dropped Mingus (and nearly everyone else jazzy) in 1973 and the tapes have languished in a box ever since. But with the help of Sue Mingus and the Jazz Workshop, this double album release, does a fantastic job of filling in some of the blanks of the Mingus story.

1972 was in the early years of Mingus’ return to playing after a musical hiatus in the second half of the ’60s, and a lot was going on. This release has a very different feel, line-up and set-list to the Charles Mingus and Friends in Concert recordings from February 1972 at Lincoln Center in NYC, and captures a fleeting snapshot of his touring European quintets and sextets as opposed to his US-based big band behemoths.

The Lost Album features a rare constellation of Mingus musicians both familiar and new playing a rare mix of familiar ’50s classics, developments of mid-’60s introspective piano pieces, and fresh in-progress compositions being workshopped live. Together, across these different pieces interspersed with short musical interludes and snippets of conversation, we are presented with a rich brew of his compositional strength and band leading spontaneity.

Orange was the Color of Her Dress, then Silk Blue might be familiar from the 1963 brief solo version on Mingus Plays Piano, although familiar may be the wrong word. It might be more familiar from the 1964 solo trumpet-led Cornell recording, but this also brings a pensive, melancholy air underpinned by a dominant bass. The Lost Album version feels much more a work-in-progress for the 1975 Changes Two version, more willing to wind up frantically or dramatically let loose the ponderous tempo, and really emphasizing the horn triumphalism of the chordal resolution at the end of the refrain.

It is both a slow, grandiose greeting to the set that introduces the sextet with ample space between musical movements, and a hint at the potentially crazed energy that together they can muster, from horn freewheeling to weary Bernard Herrmann-esque saxophone glissando.

In this 30-minute epic, mixed with the trademark Mingus organised chaos, are a series of more personal conversations – Mingus with tenor, Mingus with alto, Mingus with trumpet, and Mingus with piano. But as the conversation slips between different phases and moods, it is Roy Brooks who flags the changes on drums: urgent, swinging, marching, scattered.

The intensity of Orange was… is lightened throughout the set, with a Noddin’ Ya Head Blues opening with a long solo bass exploration, before launching into a slow blues and an awkwardly dated lyric vocal chorus from John Russell Foster, and a delightfully dated Louis Armstrong homage in Pops. On Pops the group almost sound like an entirely different band – nimble and pliable clarinet from tenor man Bobby Jones, and a clean upright trumpet style.

Hearing the early development of Jon Faddis on trumpet on The Lost Album is for me one of the choice discoveries. The sextet gel together well, coming at the tail end of a European tour and the last days of their two-week residency at Ronnie Scott’s. But Faddis is only 19 years old (or 11, as Mingus quips) and is a hero throughout.

His storming solo on an unnervingly fast and particularly chaotic Fables of Faubus is flexible, varied, wildly high. Fables… brings the best out of each musician as well as the arrangement they play through, hung on the architecture of one of Mingus’ most compelling compositions. Mind-readers’ Convention in Milano is another master class in bringing the group together in lockstep, allowing melodies to collide, overwhelming serpentine lines crashing through speeds and each other, the staggered lines locking together to become more than the sum of their parts. The Man who Never Sleeps leads with a piercing, searching Faddis line, before slipping into a cool swing, and sombre Charles McPherson alto saxophone solo. It is a clean finish to the set (not without a virtuosically long drum solo and a release of some of the tension built in the early parts).

Mingus closes the set with the slightly unusual phrasing “Thank you for coming here to get your claps on record”, which sounds even more unusual considering that record was unexpectedly buried for a half-century. But as well as their applause, the crowd have helped shape the arc and energy of The Lost Album, two and a half hours of high fidelity new perspectives on Mingus developments; transitional fossils that help us understand his work before and after better than we did before.

Charles Mingus, bass

Jon Faddis, trumpet

Charles McPherson, alto saxophone

Bobby Jones, tenor saxophone, clarinet

John Foster, piano, vocals

Roy Brooks, drums, musical saw

Recorded Live at Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club in London, England on August 14 and 15, 1972

Digitally remastered

Charles Mingus

One of the most important figures in twentieth century American music, Charles Mingus was a virtuoso bass player, accomplished pianist, bandleader and composer. Born on a military base in Nogales, Arizona in 1922 and raised in Watts, California, his earliest musical influences came from the church– choir and group singing– and from “hearing Duke Ellington over the radio when [he] was eight years old.” He studied double bass and composition in a formal way (five years with H. Rheinshagen, principal bassist of the New York Philharmonic, and compositional techniques with the legendary Lloyd Reese) while absorbing vernacular music from the great jazz masters, first-hand. His early professional experience, in the 40′s, found him touring with bands like Louis Armstrong, Kid Ory and Lionel Hampton.

Eventually he settled in New York where he played and recorded with the leading musicians of the 1950′s– Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Bud Powell, Art Tatum and Duke Ellington himself. One of the few bassists to do so, Mingus quickly developed as a leader of musicians. He was also an accomplished pianist who could have made a career playing that instrument. By the mid-50′s he had formed his own publishing and recording companies to protect and document his growing repertoire of original music. He also founded the “Jazz Workshop,” a group which enabled young composers to have their new works performed in concert and on recordings.

Mingus soon found himself at the forefront of the avant-garde. His recordings bear witness to the extraordinarily creative body of work that followed. They include: Pithecanthropus Erectus, The Clown, Tijuana Moods, Mingus Dynasty, Mingus Ah Um, The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, Cumbia and Jazz Fusion, Let My Children Hear Music. He recorded over a hundred albums and wrote over three hundred scores.

Although he wrote his first concert piece, “Half-Mast Inhibition,” when he was seventeen years old, it was not recorded until twenty years later by a 22-piece orchestra with Gunther Schuller conducting. It was the presentation of “Revelations” which combined jazz and classical idioms, at the 1955 Brandeis Festival of the Creative Arts, that established him as one of the foremost jazz composers of his day.

In 1971 Mingus was awarded the Slee Chair of Music and spent a semester teaching composition at the State University of New York at Buffalo. In the same year his autobiography, Beneath the Underdog, was published by Knopf. In 1972 it appeared in a Bantam paperback and was reissued after his death, in 1980, by Viking/Penguin and again by Pantheon Books, in 1991. In 1972 he also re-signed with Columbia Records. His music was performed frequently by ballet companies, and Alvin Ailey choreographed an hour program called “The Mingus Dances” during a 1972 collaboration with the Robert Joffrey Ballet Company.

He toured extensively throughout Europe, Japan, Canada, South America and the United States until the end of 1977 when he was diagnosed as having a rare nerve disease, Amyotropic Lateral Sclerosis. He was confined to a wheelchair, and although he was no longer able to write music on paper or compose at the piano, his last works were sung into a tape recorder.

From the 1960′s until his death in 1979 at age 56, Mingus remained in the forefront of American music. When asked to comment on his accomplishments, Mingus said that his abilities as a bassist were the result of hard work but that his talent for composition came from God.

Mingus received grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, The Smithsonian Institute, and the Guggenheim Foundation (two grants). He also received an honorary degree from Brandeis and an award from Yale University. At a memorial following Mingus’ death, Steve Schlesinger of the Guggenheim Foundation commented that Mingus was one of the few artists who received two grants and added: “I look forward to the day when we can transcend labels like jazz and acknowledge Charles Mingus as the major American composer that he is.” The New Yorker wrote: “For sheer melodic and rhythmic and structural originality, his compositions may equal anything written in western music in the twentieth century.”

He died in Mexico on January 5, 1979, and his wife, Sue Graham Mingus, scattered his ashes in the Ganges River in India. Both New York City and Washington, D.C. honored him posthumously with a “Charles Mingus Day.” (Source: www.mingusmingusmingus.com)

Booklet for The Lost Album From Ronnie Scott's (Live) (Remastered)