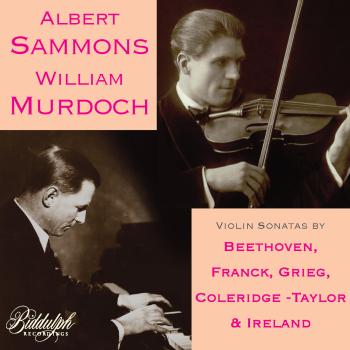

Albert Sammons & William Murdoch

Biography Albert Sammons & William Murdoch

Albert Sammons

Apart from some initial tutoring from his father Sammons was largely self-taught but achieved a high degree of technical prowess. In 1908, performing Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto at the Waldorf Hotel, he was noticed by Sir Thomas Beecham who then engaged him as leader of his orchestra. Sammons went on to impress audiences, including royalty, with his solo appearances and later became leader of the Ballets Russes and the Philharmonic Society orchestra.

The importance of Sammons in the history of British music-making should not be underestimated. For around two centuries Britain had suffered a dearth of eminent or notable musicians and habitually imported foreign celebrities whilst under-investing in its own arts practitioners. Sammons’s arrival marks something of a renaissance in this respect (one that was recognised quickly by a native audience coincidentally starved of the usual exotic talent by the events of World War I) and it complements the new canon of British composition launched by Parry, Stanford, Elgar et al. towards the end of the nineteenth century. Upon hearing him play, Ysaÿe proclaimed: ‘At last, England has found herself a great violinist!’ Sammons’s close association with Elgar’s Violin Concerto further cements his place in the nation’s musical history. He first performed it in 1914 (some four years after its première at the hands of Kreisler, the work’s dedicatee) and continued to champion it throughout his career. Elgar himself acknowledged Sammons’s ability to deliver the work with more insight than any other violinist of his day. Like Elgar, Sammons disliked travel and was uninterested in promoting his reputation abroad; he thus remains relatively unknown and undervalued in the world at large, although he did enjoy private chamber music sessions with the likes of Ysaÿe, Thibaud and Rubinstein on their visits to England.

A keen exponent of new music, Sammons took an active part in revising and preparing Delius’s Violin Concerto for publication and giving its first performance; Delius bestowed equal approval upon Sammons as an interpreter of his own work as Elgar had done with his. Sammons introduced several compositions in recitals with pianist William Murdoch, whom he met whilst playing (as a clarinettist!) in the band of the Grenadier Guards. This partnership was a long-standing and fruitful one, expanding from time to time to include violist Lionel Tertis and cellists Lauri Kennedy, Cedric Sharpe and W.H. Squire. In 1916 Sammons gave the UK première of Debussy’s Violin Sonata, but he is better known for introducing works by British composers such as Vaughan Williams, Ireland, Howells and Rubbra. In 1919 he led premières of Elgar’s Piano Quintet and String Quartet and in 1942 brought a concerto by the now little-known George Dyson (1883–1964) to the public stage.

He made forays into composition himself with a number of books of studies, several solo pieces and, notably, his ‘Phantasy’ String Quartet which won a Cobbett prize.

Among his pupils at the Royal College in London were Alan Loveday and Hugh Bean; the latter swore by his collected volumes of exercises Secrets of Technique and recalled how Sammons ‘would either describe what he wanted in a straightforward way […] or demonstrate […] how the problem could be analysed in a way that would be relevant to the particular pupil […] Anything that resembled a gimmick or streamlining for effect would be absolutely alien to him.’

Sammons made many recordings, most famously Elgar’s Violin Concerto with the New Queen’s Hall Orchestra under Henry Wood in 1927 (the first complete recording of the work), and in 1934 Elgar’s Violin Sonata with his long-standing duo partner Murdoch. The concerto reveals a subtle and lithe technique with incredibly precise intonation and well-rounded tone. Sammons’s style reflects the newer aesthetic of the early twentieth century; he used an almost continuous vibrato, generally slower than today’s use of the device, and retained a fondness of the portamento. This recording is often compared with the equally famous Yehudi Menuhin/London Symphony Orchestra version of 1932 under Elgar’s baton and can be praised for its more direct approach, significantly faster and arguably less maudlin in the slow movement. The sonata recording is well-loved also and shows deep insight, with a particularly expressive approach to rhythm. The Sammons/Murdoch duo also recorded Beethoven’s ‘Kreutzer’ Sonata (1927) in an equally distinguished and vibrant performance, whilst a clean, well coordinated and inspiring 1926 reading of the ‘Archduke’ Trio with W.H. Squire is notable for being not only the first electric recording of this work, but also a compelling alternative to the better-known Casals / Thibaud / Cortot recording of two years later.

Sammons was a persuasive advocate of Delius’s works and his 1944 recording of the Violin Sonata No. 3 with Kathleen Long shows that he maintained his malleable musicianship into the 1940s. On record, Sammons is not only a testament to the changing performing practices of the first half of the twentieth century but also quite clearly an artist of international rank, well deserving of the affection in which he is still held.

William Murdoch

After initial studies at Melbourne University where he was to have read law, William Murdoch won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music and moved to London in 1906. After four years of study he made his London debut in 1910 and was ready to embark on a career as a touring pianist which took him to South Africa in 1911, followed by Australia and New Zealand during 1912 and 1913. In 1914, having made his first appearances in America and Canada, he volunteered for active service in World War I, but was deemed unfit. Instead, in 1917 he was sent to Scandinavia on artistic propaganda work where, after the war, he made four more tours. It was in London that he made his home and where he formed musical partnerships with chamber instrumentalists of the day, particularly Albert Sammons, Arthur Catterall, Lionel Tertis and W. H. Squire. In 1919 he took part in the first performance of Elgar’s Piano Quintet. From 1930 to 1936 he taught at the Royal Academy of Music in London and at this time published two books, one on Brahms for the centenary year of 1933 and another on the life of Chopin in 1934. Murdoch was a modest man and never sought the life of a famous virtuoso. His death came at the untimely age of fifty-four.

Most of Murdoch’s records were made for Columbia. He began to record in the acoustic era: encore pieces, movements from trios with Squire and Catterall; also the first commercial recording of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 Op. 37 with Hamilton Harty. Murdoch did not like the recording studio and many of his electrical recordings were made in an empty Wigmore Hall. He felt that one of his best records was of Chopin’s Ballade in A flat Op. 47 and at the time of its release (1928) his touch was compared to that of Vladimir de Pachmann. Murdoch disliked Liszt’s music but admired the man; he did, however, record Liszt’s La Campanella. He regarded Busoni as the greatest Liszt performer of his day and Rachmaninov as one of the greatest pianists. The major works he recorded for solo piano are by Beethoven, his ‘Pathétique’ and ‘Appassionata’ Sonatas. Murdoch’s performances have fast tempi and tight rhythms and a clarity that he also displays in his Chopin playing. He said that although Beethoven performances needed iron, they should not be merely rugged or rough.

Murdoch is represented on disc by much chamber music and he is perhaps remembered more in this field rather than as a soloist. Successful recordings of the Elgar Violin Sonata and Beethoven’s ‘Kreutzer’ Sonata Op. 47 (with Catterall), the Tchaikovsky Trio, and an adaptation of the Mendelssohn C minor Trio all show his sensitivity and affinity for chamber music. In the ‘Archduke’ Trio, where he is joined by Sammons and Squire, we are treated to a genial gathering of friends playing some of their favourite music. Also of note are six ten-inch discs he made of test pieces for the Daily Express National Piano Playing Contests in 1927. Not only does he perform works by John Ireland, York Bowen and Alec Rowley, but he also comments on them.