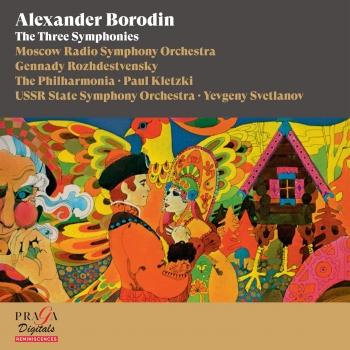

Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra, Gennady Rozhdestvensky, The Philharmonia, Paul Kletzki, USSR State Symphony Orchestra, Yevgeny Svetlanov

Biography Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra, Gennady Rozhdestvensky, The Philharmonia, Paul Kletzki, USSR State Symphony Orchestra, Yevgeny Svetlanov

Gennady Rozhdestvensky

Rozhdestvensky’s parents were both musicians of the highest calibre: his father was the conductor Nikolai Anosov, a major musician of the Soviet era, a fine pianist, and a composer who spoke ten languages; and his mother was the soprano Natalya Rozhdestvenskaya, a star of the Bolshoi Opera, whose name he adopted. He studied first at the Gnessin Institute of Music, and then at the Moscow Conservatory; here he was a piano pupil of Lev Oborin, and a conducting pupil of his own father. When Rozhdestvensky was twenty he made his public debut at the Bolshoi Theatre conducting Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker, having already achieved distinction as the conductor of prizewinning student orchestras at international music competitions in Bucharest and Berlin. He served as a conductor at the Bolshoi Theatre between 1951 and 1961, assisting the distinguished conductor of the ballet company, Yuri Fayer; deputising for an ailing Samuel Samosud in an early performance of Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 10 in 1955; first visiting Great Britain with the Bolshoi’s ballet company in 1956; and, together with Alexander Melik-Pashayev, leading the first performances at the Bolshoi of Prokofiev’s opera War and Peace in 1959. During the 1960s he held two major posts in Russian musical life: between 1961 and 1974 he was chief conductor of the Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra, also known as the All-Union Radio and Television Orchestra, and from 1964 to 1970 he was chief conductor of the Bolshoi Theatre. Major musical landmarks of this period included the first Russian performances of Benjamin Britten’s opera A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Bolshoi in 1965, and an electrifying account of Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in 1970.

After helping to found the Moscow Chamber Opera in 1972 and serving as the company’s first music director, Rozhdestvensky conducted abroad a great deal. He succeeded Antal Dorati as chief conductor of the Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra in 1974, remaining with this orchestra until 1977, after which he became chief conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra from 1978 to 1981. He left London to become chief conductor of the Vienna Symphony Orchestra between 1981 and 1983; while in Vienna he maintained an important Russian tradition by teaching conducting at the Vienna Academy of Music, having already been professor of conducting at the Moscow Conservatory. He was later to continue to teach, at the Accademia Chigiana in Siena from 1987. Rozhdestvensky returned to a permanent appointment in Russia in 1982 when the Ministry of Culture formed a symphony orchestra, named after itself, for him to lead. With this orchestra he recorded a large discography, including the complete symphonies of Shostakovich, Glazunov, Bruckner, Schnittke and Honegger. Between 1991 and 1995 Rozhdestvensky returned to the helm of the Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra as its chief conductor; and he was also to return to the Bolshoi Theatre for its 2000–2001 season as artistic director for both the ballet and opera companies, the first such appointment in the theatre’s history. His period there culminated with the world première of the original version of Prokofiev’s opera The Gambler. In 1969 Rozhdestvensky married the brilliant pianist Viktoria Postnikova, who first shot to fame at the Leeds International Piano Competition; their son is the internationally acclaimed violinist Alexander, or Sasha, Rozhdestvensky.

As an interpreter Rozhdestvensky combines a high degree of spontaneity with a grand sense of gesture and an infallible placing of climaxes, resulting in highly satisfying and individual performances. He is a master of baton technique, often using a long stick, which, when combined with his expansive gestures, has a mesmeric as well as a commanding effect upon both orchestras and audiences. His vast musical appetite and his unfailing enthusiasm for twentieth-century Russian composers are most clearly displayed in his discography, which is enormous and chronicles his career in considerable detail. In addition to the numerous recordings which he made for the Soviet state record company, Melodya, there are numerous live recordings from the Soviet period in his career, many of which well illustrate his extraordinary command of the orchestra. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union Rozhdestvensky has recorded extensively for many different labels, most notably Chandos. Rozhdestvensky is a musician of the highest calibre and a true master of his art, whose recordings of contemporary Russian music are both authoritative and empathetic.

Paul Kletzki

was born into a vigorous Jewish community and began his musical studies early, quickly gaining recognition for his skills both as a violinist and as a pianist. He attended the Warsaw Conservatory, where he was taught by the violinist and conductor Emil Młynarski, and also Warsaw University; and moved to Berlin in 1921 to continue his studies at the High School for Music where he came under the influence of two major figures of the period: the composer Arnold Schoenberg and the conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler. Kletzki was leader of the Łodź Philharmonic Orchestra from 1916 to 1919, but saw himself primarily as a composer. He wrote a significant body of work between 1921 and 1933, including two large symphonies, a capriccio, three string quartets and at least twenty songs, and made his conducting debut in 1923 in a concert of his own music. Furtwangler also performed Kletzki’s music, recommending his work to the publisher Simrock and inviting him to conduct the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in 1928 in a programme that included his violin concerto. This was well received, as was his piano concerto at its first performance in Leipzig in 1932. All his compositions were published, but were then proscribed by the National Socialist Party when it came to power in 1933, and as a result Kletzki’s publishers destroyed all his printed music and melted down their printing plates.

Kletzki fled to Italy, taking printed and manuscript copies of his music with him in a metal trunk and teaching in Milan at the Scuola Superiore di Musica. During 1937 and 1938 he also held the post of chief conductor of the Kharkov Philharmonic Orchestra in Russia, but had to quit this position because he was of Polish origin. Mussolini’s Fascists were no kinder towards Jews than the Nazis, with the result that in 1939 Kletzki was forced to flee once again. Unable to take his trunk of music with him, he hid it in a basement near Milan’s opera house, La Scala, and settled in Switzerland with his wife, who was Swiss. Here he wrote his last works, including his Symphony No. 3 of 1939, subtitled ‘In Memoriam’. Kletzki has been quoted as saying that the Holocaust, and the loss of his music (and especially the fact that his publisher had even melted down the printing plates) killed in him the desire to compose. During World War II he taught at the Lausanne Conservatory, and between 1943 and 1949 he conducted the Lucerne Festival Orchestra in concerts which helped him to establish an international reputation. He appeared in Paris shortly after the liberation, conducting Mahler’s Symphony No. 1, and was invited by Toscanini to participate in the celebrations surrounding the reopening of La Scala in 1946. In the autumn of that year Walter Legge invited him to record with his recently formed Philharmonia Orchestra, which he also conducted in concerts, as well as the London Philharmonic and Royal Philharmonic Orchestras.

For the rest of Kletzki’s life his conducting career flourished. He appeared regularly throughout Europe as a guest conductor, becoming a Swiss citizen in 1949, and toured Australia in 1948, once again performing some of the symphonies of Mahler. With the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra he appeared on tour in Europe during 1955, having previously with this orchestra recorded for Legge and the Columbia label in 1954 Mahler’s Symphony No. 9 and Schoenberg’s Verklarte Nacht. Kletzki was chief conductor of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra for the 1954–1955 season, but, as had previously been his experience in Russia, was unable to continue in this role because of British Civil Service rules concerning the engagement of foreigners. He made his American debut in 1957 with the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, and also led concerts with the Chicago Symphony and Philadelphia Orchestras. The success of these appearances resulted in him being appointed as chief conductor of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra for three seasons between 1958 and 1961: together with Antal Dorati he is credited in Dallas with significantly developing the orchestra’s playing standards.

The cellist Mimi McShane, who was hired by Kletzki, had vivid recollections of his time in Dallas: ‘He was very European, very old-fashioned. He liked to throw tantrums, but everybody really respected him, and what he said about the music was the word of God. As a conductor, his technique was perfect. He didn’t really get along with the Dallas social scene, though. I imagine the Dallas lifestyle was very alien to him.’

Kletzki left the Dallas orchestra ostensibly because of its inability to secure a recording contract, and henceforth confined himself to appearances in Europe because of his wife’s weakening health. Later appointments included the chief conductorships of the Berne Symphony Orchestra (1964–1967) and of Ernest Ansermet’s Suisse Romande Orchestra (1967–1970), with which its founder maintained a close connection until his death in 1969. Kletzki returned to his musical roots late in his life through guest appearances with the Warsaw Philharmonic and the Czech Philharmonic Orchestras, with whom he recorded a much-admired cycle of the Beethoven symphonies. In 1965 a construction crew working near La Scala in Milan found the metal trunk in which he had placed his music before World War II, but Kletzki was never to open it, afraid that, having lost his music once, it might have been destroyed a second time by nature. He died unexpectedly in 1973 while working with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra.

Interviewed by Tully Potter, the leader of the Lucerne Festival Orchestra, Peter Rybar, gave a graphic description of Kletzki as a conductor: ‘He conducted very well, with lovely gestures – it was very professional conducting – and he was very emotional, he was almost crying sometimes.’ The same point is made by the biographer of the Philharmonia Orchestra, Stephen Pettitt, who also noted Kletzki’s useful background as a string player: ‘Kletzki’s experience as a player made his conducting gestures particularly sympathetic to the strings of the Philharmonia Orchestra, to whose tone he brought a bloom – ‘the burning sound!’ as he demanded from them. He was a very emotional conductor, too; his desire for warmth of string sound came from this emotionalism. “Cry it!” he would beg, tears rolling down his cheeks as if in sympathy, and the tone came.’

Kletzki’s discography is large. He recorded consistently from the advent of tape recording and the long-playing record until his death: initially for EMI, and subsequently for several other labels, notably the Concert Hall Record Club, Decca and Supraphon. He was equally adept as a symphonic conductor and as an accompanist. Among his many outstanding records are very fine accounts of Mahler’s Symphonies Nos 1 and 4 and Das Lied von der Erde (with Murray Dickie and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau); Sibelius’s Symphonies Nos 1 and 2; Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6 ‘Pathetique’ and Manfred Symphony; and a powerful reading of Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 5, as well as numerous shorter works. Two outstanding concerto recordings are Berg’s Violin Concerto, with the Belgian violinist Andre Gertler, and Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 1, with Maurizio Pollini. For Concert Hall Kletzki added Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4 and Beethoven’s Symphonies Nos 1, 3, 5 and 6 to his recorded repertoire. His final recordings for Decca, with the Suisse Romande Orchestra, maintained this high standard, and included emotional accounts of Rachmaninov’s Symphonies Nos 2 and 3 and Nielsen’s Symphony No. 5, as well as Hindemith’s Symphony, Mathis der Maler and Lutosławski’s Concerto for Orchestra. As the archives of many European radio stations are gradually explored in depth, more performances conducted by Kletzki have appeared. These include refulgent accounts of Brahms’s Double Concerto, with Adolf and Hermann Busch and the French National Radio Orchestra, and of the same composer’s Symphony No. 4 with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra.

Yevgeni Svetlanov

was born in Moscow on 6 September 1928 into a family of musicians and artists. His parents were both members of the Bolshoi Theatre company and his mother, née Kruglikova, appeared as Tatyana in “Eugene Onegin ” and performed the lead role in “Madame Butterfly ” : from early childhood, Evgeny was captivated by the theatre and for example appeared as the son of Cio-Cio-San on the most prestigious lyrical stage of the Soviet Union (it was precisely in memory of this recollection that he conducted his last performance of Puccini’s opera in Montpellier, one month before his death – thus the cycle was ended).

He studied at the Gnessin school until 1951 and at the Moscow Conservatory until 1955, attending the conducting classes of Mikhail Gnessin and Yuri Chaporin, whose oratorios and cantatas he subsequently recorded; his piano teacher was the great Heinrich Neuhaus ; his conducting mentor was Alexander Gauk, the founder of the USSR State Symphony Orchestra in 1936 and an emblematic figure of modern interpretation. As Svetlanov explains, “Before the Revolution, even though there were some excellent conductors, such as Balakirev and Rubinstein, there was no genuine Russian conducting school: Gauk created it and if only for this his name should remain in the annals of our musical history”. Celebrities such as Alexander Melik-Pacheiev and Evgeny Mravinsky also studied under Gauk.

Svetlanov gave his first concert performances as a conductor on the radio as early as 1953, while he was still a student. Two years later, he returned to the Bolshoi as principal assistant: in 1962, he was appointed principal conductor, becoming honorary principal conductor in 1999, when he conducted a new performance of “The Maid of Pskov” He had become familiar with the great operas of Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Borodin and Mussorgsky, as well as a large number of ballets that enabled him to perfect his technique and his knowledge of Russian musical literature while facing the constraints of alternating performances in a repertory theatre. In 1964, he led the Bolshoi’s first tour in Italy, which proved a resounding success.

The following year, Evgeny Svetlanov took over the USSR State Symphony Orchestra, which he had known for ten years, and headed the orchestra for over thirty five seasons, ranging from subscription concerts in Moscow (and all over the Soviet Union) to phenomenally successful overseas tours and a countless number of recordings: during his tenure with the orchestra the maestro recorded an anthology of Russian music covering both the entire romantic and post-romantic period to modern times. This was a monumental task that Svetlanov conducted methodically over twenty five years while interpreting, both on record and in the concert hall, the German ( from Mozart to Schönberg, with a marked preference for Mahler) and French repertoires (Debussy, Ravel and Dukas,with the notable exception of Berlioz). Two hundred and fifty CDs would be required in order to republish this anthology which represents an encyclopaedia of Russian symphony and concert works. However Svetlanov completed over three thousand recordings throughout his career for Russian, Japanese, French, British and Dutch record companies.