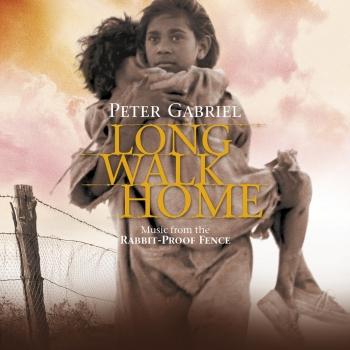

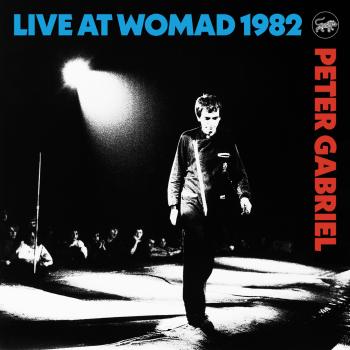

Peter Gabriel 3: Melt (Remastered) Peter Gabriel

Album Info

Album Veröffentlichung:

2009

HRA-Veröffentlichung:

15.11.2019

Das Album enthält Albumcover

Entschuldigen Sie bitte!

Sehr geehrter HIGHRESAUDIO Besucher,

leider kann das Album zurzeit aufgrund von Länder- und Lizenzbeschränkungen nicht gekauft werden oder uns liegt der offizielle Veröffentlichungstermin für Ihr Land noch nicht vor. Wir aktualisieren unsere Veröffentlichungstermine ein- bis zweimal die Woche. Bitte schauen Sie ab und zu mal wieder rein.

Wir empfehlen Ihnen das Album auf Ihre Merkliste zu setzen.

Wir bedanken uns für Ihr Verständnis und Ihre Geduld.

Ihr, HIGHRESAUDIO

- 1 Intruder 04:54

- 2 No Self Control 03:55

- 3 Start 01:21

- 4 I Don't Remember 04:41

- 5 Family Snapshot 04:28

- 6 And Through The Wire 05:00

- 7 Games Without Frontiers 04:06

- 8 Not One Of Us 05:21

- 9 Lead A Normal Life 04:14

- 10 Biko 07:32

Info zu Peter Gabriel 3: Melt (Remastered)

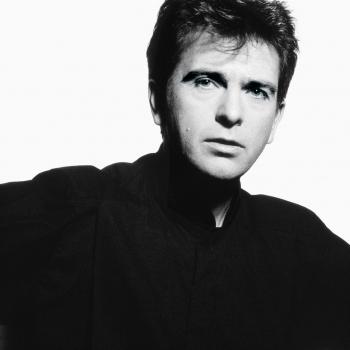

Peter Gabriel is the third eponymous solo album by English rock musician Peter Gabriel, released on 23 May 1980 by Charisma Records. The album has been acclaimed as Gabriel's artistic breakthrough as a solo artist and for establishing him as one of rock's most ambitious and innovative musicians.

Recorded both at his home studio at Ashcombe House, near Bath, and at London’s Townhouse Studios, Peter’s third self-titled album was produced by Steve Lillywhite. The album saw Peter change his writing style; now the rhythm came before the melody and the songs were built up on top of the rhythmic sequences. The album delivered a top 5 UK single in Games Without Frontiers and Peter’s first overtly political song in the shape of totemic closer Biko. It also features notable contributions from Kate Bush, Paul Weller, Phil Collins and David Rhodes.

“I think that the third album was quite important for me in terms of really having a defining sound and the band coming through. It was the first record where I was clearly doing something different from what other people were doing.

I was looking around for some young, new and interesting people that I could work with. Steve Lillywhite and Hugh Padgham had worked on the XTC record, and some other what were then alternative bands, and of the people I had met I enjoyed their work a lot.

There was a drum sound that Hugh Padgham had experimented with, using SSL gates, on the XTC record that I was very excited about. There was this huge resonant sound that would be trapped down in sort of square shapes and then flattened into nothing. It was a very big and aggressive sound. So I then thought I’d build a track around it, which was the track Intruder. Phil Collins who I got in for that, then went on to take Hugh and work on his own record using a lot of those sounds, but there was a real sense of discovery when that first arrived.

One of the other influences at that time was some of the ‘Systems Music’ that was beginning to evolve. Steve Reich had done this wonderful record called ‘Music for Eighteen Musicians’, which involved marimbas and I think, of all the ‘systems’ composers, his work had a lot of textures and colours and grooves to them that I really responded to. So I tried to involve elements of that in the work. I also worked with a wonderful percussionist Morris Pert and ‘No Self Control’ would be one track, which integrated some of those things and a band sound as well.

This album was the first time that I had a chance to work with Kate Bush who was singing on ‘Games Without Frontiers’. I’d heard ‘Wuthering Heights’, which I really liked; I thought she had an extraordinary, wonderful voice and was doing great things as a writer. Then obviously I went on to work with her again in the future on ‘Don’t Give Up’.

Paul Weller was also working down in the studio and he came in on the session and so it was an odd assembly of people.

I think ‘Family Snapshot’ was another important track for me on that record which was based on this Assassin’s Diary book [An Assassin’s Diary – Arthur Bremer] which had been found under a bridge in Washington; a discarded notebook, which had somewhat strange ramblings of someone who wanted to assassinate governor George Wallace. So I mixed that in with some of the Kennedy stuff, so it was really an account of an assassination, but from the assassin’s point of view.

‘Not One Of Us’ was about racism, about being an outsider.

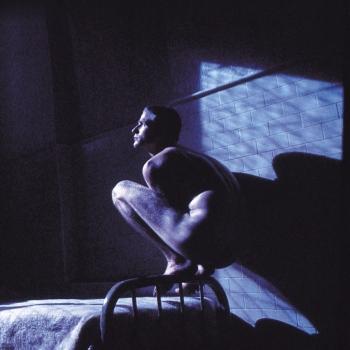

‘Lead A Normal Life’ was about being in a mental hospital and the sense of isolation.

‘Biko’ became a very important song for me. I’d not written an overtly political song before and was wondering if it would be accepted… I had various doubts and Tom Robinson, who I’d got to know at the time, who was championing various causes, but the gay cause is what he was most identified with at the time, was really telling me that I should just steam ahead and do it anyway and put it out and that it didn’t matter really what people thought of my motives; if it got attention and money in the right direction. That, I think, put my mind at rest and later on I think it lead me towards some of the human rights stuff, which I’m still very much involved with today. So it was as much a thing that helped shape me as the other way round.

The album was full of, what at the time were ‘strange’ sounds. I remember when I met Ahmet Ertegun [founder of Atlantic Records] and he’d first heard that record, which Atlantic later dropped, he’d asked if I’d been hospitalised myself and obviously thought that I’d gone from being some sort of pop artist to some strange backwater. In the end Polygram took the record up in America and it did quite well, with some success for ‘Games Without Frontiers’, but at the time I remember the A&R guys were trying to encourage me to sound like the Doobie Brothers. One of the main jobs of the A&R Department of a record company is to try and make records that they’re going to sell. So they look at what’s selling at the moment and they try and get all of their artists to sound like that. At the same time, to be fair, I’ve worked with some really good A&R people who’ve made some very good musical points and have a lot of interesting input, but I’m very fortunate to have grown up in a time, in the post-Sixties, when artists were allowed to get on making their own mistakes, doing what they needed to do. You could listen to your record company, but you didn’t have to.

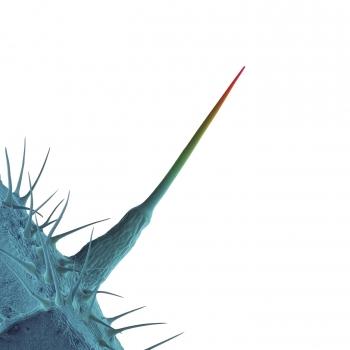

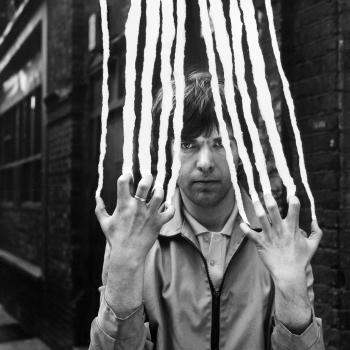

We did the sleeve with Storm again at Hipgnosis and he introduced me to these things called Krimsographs. There was a photographer called Les Krims who discovered that if you take a Polaroid and you squash it you can get the colours to run. There’s a whole book, quite a little subsection of photography, devoted to the art of squashing Polaroids. And on this session we did many, many pictures with the Polaroid and everyone was squashing them; we probably had about three hundred different squashed Polaroids and we used to go after them with different objects – burnt matches, coins, fingers and all sorts of things. It was a lot of fun because you had to get the timing right, but you got some wonderful effects out of the distortions. We have a poster with all the different failures or the ones that we didn’t use which was a good piece of work.

I’d had a dream of a melting face, some kind of wax effigy caught possibly in a museum fire. To achieve the painterly dripping effect we used ordinary Polaroids (after Les Krims) and if one pushes around the developing picture sandwiched between two bits of plastic with a blunt instrument like the end of a pencil the image is then smeared as it develops. Since this procedure is dead easy we did it loads of times along with Pete Gabriel in disfiguring himself by manipulating Polaroids as they ‘developed’. Peter impressed us greatly with his ability to appear in an unflattering way, preferring the theatrical or artistic to the cosmetic. Because we couldn’t decide on a favourite, for they were all great fun, we used lots” – Storm Thorgerson.

The other stuff from that period… It was my first bald tour and there it was voluntary baldness…

One of the things at that time was that a lot of bands were keen to get be the first to play in China. There was a lot of press about it. So I thought that I would do the tour merchandise for a fictitious Chinese tour and it was the Tour of China 1984. We used Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book which had had more copies of it sold, or at least distributed, than any other book, as the model for the tour programme. That was fun to do.”

Peter Gabriel, lead vocals, backing vocals, piano, synthesizer, drum pattern, whistle

Kate Bush, backing vocals

Dave Gregory, guitar

Robert Fripp, guitar

David Rhodes, guitar, backing vocals

Paul Weller, guitar

Larry Fast, synthesizer, bagpipes

John Giblin, bass

Tony Levin, Chapman Stick

Jerry Marotta, drums (4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10), percussion (7, 8)

Phil Collins, drums (1, 2, 6); drum pattern (1); snare (5); surdo (10)

Dick Morrissey, saxophone

Morris Pert, percussion

Dave Ferguson, screeches

Recorded Spring–summer 1979 at Bath and Townhouse in London

Produced by Steve Lillywhite

Digitally remastered

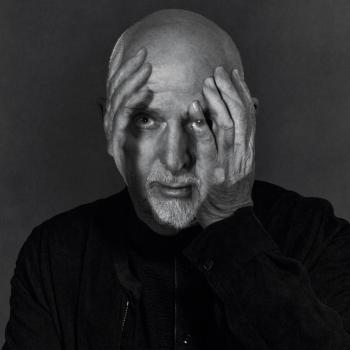

Peter Gabriel

has earned a worldwide reputation for his innovative work as a musician, writer and video maker. When at school he co-founded the group Genesis, which he left in 1975. His albums, live performance and videos since then have won him a succession of awards. Gabriel has released eleven solo albums and in 1986, his album 'So' won him his first Grammy. The videos from this project confirmed him as a leader in video production and included 'Sledgehammer', which has won the most music video awards ever, including number one position in 'Rolling Stones' top 100 videos of all time and the MTV most played video of all time.

Dieses Album enthält kein Booklet