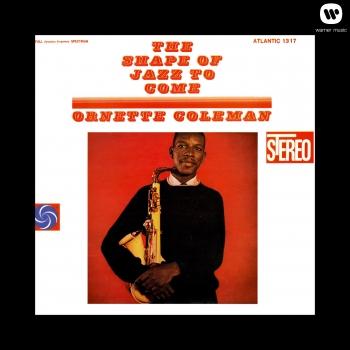

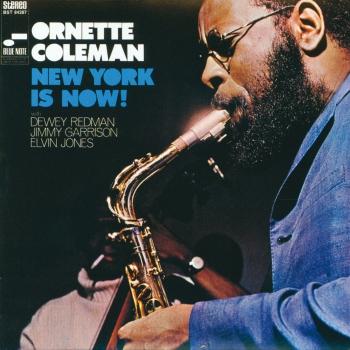

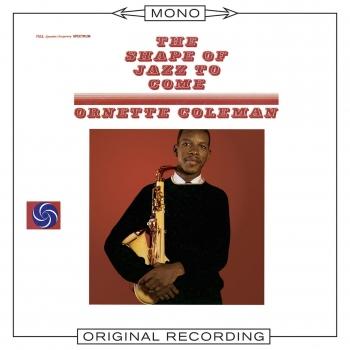

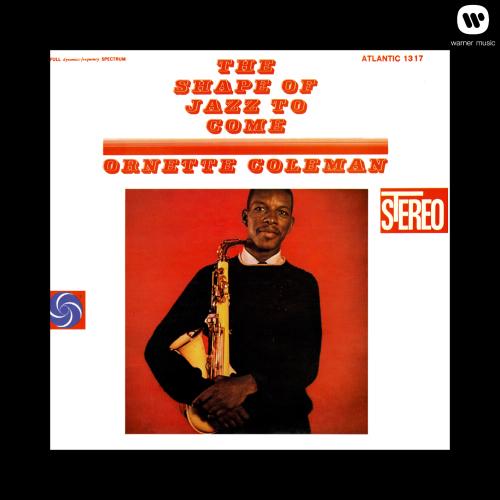

The Shape Of Jazz To Come (Stereo) Ornette Coleman

Album Info

Album Veröffentlichung:

1959

HRA-Veröffentlichung:

13.07.2013

Das Album enthält Albumcover

Entschuldigen Sie bitte!

Sehr geehrter HIGHRESAUDIO Besucher,

leider kann das Album zurzeit aufgrund von Länder- und Lizenzbeschränkungen nicht gekauft werden oder uns liegt der offizielle Veröffentlichungstermin für Ihr Land noch nicht vor. Wir aktualisieren unsere Veröffentlichungstermine ein- bis zweimal die Woche. Bitte schauen Sie ab und zu mal wieder rein.

Wir empfehlen Ihnen das Album auf Ihre Merkliste zu setzen.

Wir bedanken uns für Ihr Verständnis und Ihre Geduld.

Ihr, HIGHRESAUDIO

- 1 Lonely Woman 04:59

- 2 Eventually 04:20

- 3 Peace 09:04

- 4 Focus On Sanity 06:50

- 5 Congeniality 06:41

- 6 Chronology 06:05

Info zu The Shape Of Jazz To Come (Stereo)

On this highly influential 1959 album, Ornette Coleman's unique writing style and idiosyncratic solo language forever changed the jazz landscape. On classics such as 'Lonely Woman,' 'Congeniality,' and 'Focus on Sanity,' Coleman used the tunes' moods and melodic contours, rather than their chords, as a basis for his improvisations. In so doing, he opened up jazz soloing immensely and ushered in new freedoms - both individually and collectively.

'1959 was a landmark for jazz recordings. Miles Davis created his Kind of Blue and John Coltrane made his Giant Steps. But the most influential jazz album made in 1959 came from Ornette Coleman... It was called The Shape of Jazz To Come.' (Martin Johnson, The Wall Street Journal)

'Coleman's sound was so out-there, one audience threw his tenor sax over a cliff. He switched to alto and pioneered free jazz: no chords, no harmony, any player can take the lead. Here, his music can be just as lyrical as it is demanding, particularly on the haunting 'Lonely Woman.' (Rolling Stone)

'Ornette Coleman's Contemporary Records releases Something Else!!!! (1958) and Tomorrow Is The Question! (1959) documented the alto saxophonist's development from the last vestiges of bebop toward a harmonically freer jazz language. Coleman's album titles became more prophetic as they were released. The Shape Of Jazz To Come is a further, but not yet completed, evolution away from harmonic harnesses of the swing and bebop eras.

If Something Else!!!! brought the jazz literati's ears to attention with its spherical, untethered solos; and Tomorrow is the Question! further justified baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan's necessary sans-piano format, then The Shape Of Jazz To Come was the 16-inch shot across the bow of conventional jazz wisdom. It paved the artistic way for the next Coleman recording, The Change Of The Century (Atlantic, 1959). Gone are the chordal patterns that guided alto saxophonist Charlie Parker out of the swing era. Gone is the harmonic anchor of piano or guitar that was a jazz mainstay for years. What is left is a gently directed independent music trajectory, a concurrent and separate mode of invention for four instruments playing with only experience and self-understanding.

The structure (if that is what it can be called) of the six pieces comprising The Shape Of Jazz To Come is presentation of a theme (or traditional head) followed by free improvisation in the solo sections by Coleman and cornetist Don Cherry followed by restatement of the theme, multiple times, in some cases. Coleman hits upon his most empathic band with bassist Charlie Haden and drummer Billy Higgins, who remain reluctant last attachments to the old ways, providing a rock-solid swing to the recording as well as their own informed solo sections without interfering with Coleman's direction.

Coleman's approach is not unlike that employed by trumpeter Miles Davis that same year on Kind Of Blue (Columbia), recorded on March 2 and April 22, 1959, where Davis entered the studio with sketches of pieces and directed the band to improvise over scales rather than chords. What Coleman did differently with The Shape Of Jazz To Come (recorded May 22, 1959) was to do away with even scalar organization, opening up the solo canvas not simply two-dimensionally, but to fully four dimensions. The result to the jazz world was a full assault on two fronts that would eventually pave the way for post bop and fusion and bolder free jazz exploration.

The Shape Of Jazz To Come in a microcosm, can be heard in 'Lonely Woman,' a tune so far reaching yet amenable to coverage—by the Modern Jazz Quartet in 1962 on Lonely Woman (Atlantic) and saxophonist John Zorn in 1989 on Naked City (Nonesuch))—that it help ease Coleman's jazz medicine down critically. The rhythm is established by Haden, strumming bass chords, and Higgins, establishing the poly-rhythms of a near Eastern Indian mantra. Coleman and Cherry add their own Eastern flourishes saturated with the blues. It is mournful and searching, with enough dissonance to distract without covering first Coleman's and then Cherry's earthy, nearly down-home solos.

The ballad (if such definitions anymore apply) 'Peace' is the most revealing track on the album. It offers Haden duets with the two soloists with appropriately minimal support form Higgins. Coleman and Cherry mix the entire history of jazz into their solos, expressing the results calmly and with purpose. Drawing from all of the genre influences surrounding him, Coleman plotted a course that led to this groundbreaking record, still, oddly, only the beginning of the revolution. In the meantime, tenor saxophonist John Coltrane, who, by the end of the next decade, would have exhausted what Coleman starts here, was in New York with Davis making a history of a different sort.' (C. Michael Bailey, All About Jazz)

Ornette Coleman, alto saxophone

Donald Cherry, cornet

Charlie Haden, double bass

Billy Higgins, drums

Recorded on May 22, 1959 at Radio Recorders, Los Angeles, California

Engineered by Bones Howe

Produced by Nesuhi Ertegun

Rolling Stone '500 Greatest Albums of All Time' #248/500

Ornette Coleman

One of the most important (and controversial) innovators of the jazz avant-garde, Ornette Coleman gained both loyal followers and lifelong detractors when he seemed to burst on the scene in 1959 fully formed. Although he, and Don Cherry in his original quartet, played opening and closing melodies together, their solos dispensed altogether with chordal improvisation and harmony, instead playing quite freely off of the mood of the theme. Coleman's tone (which purposely wavered in pitch) rattled some listeners, and his solos were emotional and followed their own logic. In time, his approach would be quite influential, and the quartet's early records still sound advanced many decades later.

Unfortunately, Coleman's early development was not documented. Originally inspired by Charlie Parker, he started playing alto at 14 and tenor two years later. His early experiences were in R&B bands in Texas, including those of Red Connors and Pee Wee Crayton, but his attempts to play in an original style were consistently met with hostility both by audiences and fellow musicians. Coleman moved to Los Angeles in the early '50s, where he worked as an elevator operator while studying music books. He met kindred spirits along the way in Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, Ed Blackwell, Bobby Bradford, Charles Moffett, and Billy Higgins, but it was not until 1958 (after many unsuccessful attempts to sit in with top L.A. musicians) that Coleman had a nucleus of musicians who could play his music. He appeared as part of Paul Bley's quintet for a short time at the Hillcrest Club (which is documented on live records), and recorded two very interesting albums for Contemporary. With the assistance of John Lewis, Coleman and Cherry attended the Lenox School of Jazz in 1959, and had an extended stay at the Five Spot in New York. This engagement alerted the jazz world toward the radical new music, and each night the audience was filled with curious musicians who alternately labeled Coleman a genius or a fraud.

During 1959-1961, beginning with The Shape of Jazz to Come, Coleman recorded a series of classic and startling quartet albums for Atlantic. With Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, Scott LaFaro, or Jimmy Garrison on bass, and Billy Higgins or Ed Blackwell on drums, Coleman created music that would greatly affect most of the other advanced improvisers of the 1960s, including John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, and the free jazz players of the mid-'60s. One set, a nearly 40-minute jam called Free Jazz (which other than a few brief themes was basically a pulse-driven group free improvisation) had Coleman, Cherry, Haden, LaFaro, Higgins, Blackwell, Dolphy, and Freddie Hubbard forming a double quartet.

In 1962, Coleman, feeling that he was worth much more money than the clubs and his label were paying him, surprised the jazz world by retiring for a period. He took up trumpet and violin (playing the latter as if it were a drum), and in 1965, he recorded a few brilliant sets on all his instruments with a particularly strong trio featuring bassist David Izenzon and drummer Charles Moffett. Later in the decade, Coleman had a quartet with the very complementary tenor Dewey Redman, Haden, and either Blackwell or his young son Denardo Coleman on drums. In addition, Coleman wrote some atonal and wholly composed classical works for chamber groups, and had a few reunions with Don Cherry.

In the early '70s, Coleman entered the second half of his career. He formed a 'double quartet' comprised of two guitars, two electric bassists, two drummers, and his own alto. The group, called 'Prime Time,' featured dense, noisy, and often-witty ensembles in which all of the musicians are supposed to have an equal role, but the leader's alto always ended up standing out. He now called his music harmolodics (symbolizing the equal importance of harmony, melody, and rhythm), although free funk (combining together loose funk rhythms and free improvising) probably fits better; among his sidemen in Prime Time were drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson and bassist Jamaaladeen Tacuma, in addition to his son Denardo. Prime Time was a major (if somewhat unacknowledged) influence on the M-Base music of Steve Coleman and Greg Osby. Pat Metheny (a lifelong Ornette admirer) collaborated with Coleman on the intense Song X, Jerry Garcia played third guitar on one recording, and Coleman had irregular reunions with his original quartet members in the 1980s.

Coleman, who recorded for Verve in the '90s, has remained true to his highly original vision throughout his career and, although not technically a virtuoso and still considered controversial, is an obvious giant of jazz. He recorded sparingly as the 21st century began, appearing on Joe Henry's Scar in 2000 and on single tracks on Lou Reed's Raven and Eddy Grant's Hearts & Diamonds, both released in 2002. (Scott Yanow) Source: Blue Note Records

Dieses Album enthält kein Booklet