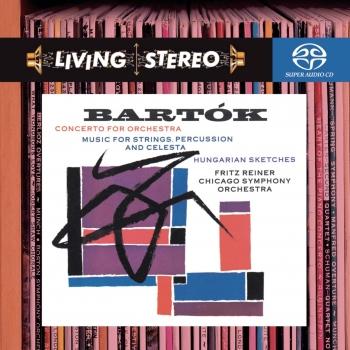

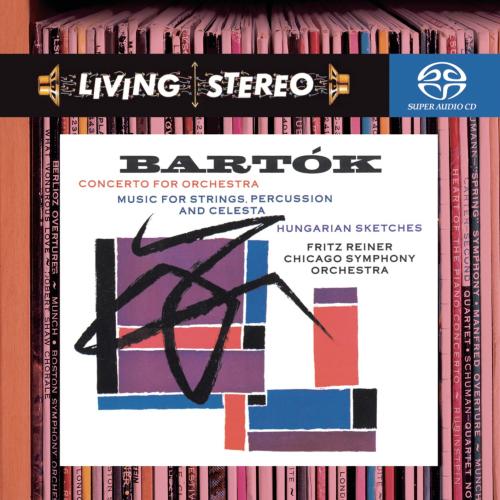

Bartók: Concerto for Orchestra; Music for Strings, Percussion & Celesta; Hungarian Sketches Chicago Symphony Orchestra & Fritz Reiner

Album Info

Album Veröffentlichung:

1955

HRA-Veröffentlichung:

27.03.2015

Label: Living Stereo

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Orchestral

Interpret: Chicago Symphony Orchestra & Fritz Reiner

Komponist: Bela Bartok (1881-1945)

Das Album enthält Albumcover Booklet (PDF)

Entschuldigen Sie bitte!

Sehr geehrter HIGHRESAUDIO Besucher,

leider kann das Album zurzeit aufgrund von Länder- und Lizenzbeschränkungen nicht gekauft werden oder uns liegt der offizielle Veröffentlichungstermin für Ihr Land noch nicht vor. Wir aktualisieren unsere Veröffentlichungstermine ein- bis zweimal die Woche. Bitte schauen Sie ab und zu mal wieder rein.

Wir empfehlen Ihnen das Album auf Ihre Merkliste zu setzen.

Wir bedanken uns für Ihr Verständnis und Ihre Geduld.

Ihr, HIGHRESAUDIO

- Bela Bartok (1881-1945): Concerto for Orchestra:

- 1 I. Introduzione - Andante non troppo - Allegro vivace 10:01

- 2 II. Giuoco delle coppie - Allegretto scherzando 06:03

- 3 III. Elegia - Andante non troppo 07:59

- 4 IV. Intermezzo interrotto - Allegretto 04:15

- 5 V. Finale - Presto 08:59

- Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta:

- 6 I. Andante tranquillo 07:05

- 7 II. Allegro con grazia 07:03

- 8 III. Adagio 06:58

- 9 IV. Allegro molto 06:44

- Hungarian Sketches:

- 10 I. An Evening in the Village 02:44

- 11 II. Bear Dance 01:41

- 12 III. Melody 02:05

- 13 IV. Slightly Tipsy 02:17

- 14 V. Swineherd's Dance from Ürög 01:57

Info zu Bartók: Concerto for Orchestra; Music for Strings, Percussion & Celesta; Hungarian Sketches

A marvellous reminder of the virtuosity of the Chicagoans under Fritz Reiner. This recording is offering superb value for money (with a playing time of over 76 minutes) as well as carefully-chosen repertoire (the ‘filler’ of Hungarian Sketches is pure delight).

Firstly, the Concerto for Orchestra. Fritz Reiner was a personal friend and confidant of the composer, so this reading carries a special authority. Not only this, Reiner’s orchestra is intensively drilled – rarely will you hear a performance so well-prepared as this. The very opening is tremendously hushed (and what clarity thanks to the 24bit remastering!). Reiner’s understanding of Bartók’s emotional vocabulary is outstanding, as is his control of his orchestra (the accelerando is surely without parallel), all this held within a beautifully warm recorded sound.

The second movement (the famous ‘Giuoco delle coppie’) is full of charm, but is also rhythmically totally on-the-ball. Fellow Hungarian Solti in his Chicago recording also found real affinity with this movement (now available on Double Decca 470 516-2), but it is Reiner who is more human. Reiner’s ‘Elegia’ is carefully sculpted, working to an excruciating (in the best sense of the word) climax. Similarly Reiner does not play down the more vulgar elements of the ‘Intermezzo interotto’ (the Shostakovich quote is blatant).

If there is any excerpt from this disc that proves the technical excellence of the Chicagoans, it is the swirling opening of the finale. Trumpets cut through the texture impressively. If there are more jubilant accounts of this finale, the interpretation is entirely in keeping with Reiner’s overall vision, with the final emergence of blazing trumpets seeming all the more victorious. It would be worth the outlay for this performance alone.

That said, there are two other claims to the record collector’s purse here. The Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, perhaps surprisingly, triumphs because of Reiner’s affinity with the more interior moments. Thus the first movement (andante tranquillo) is a peaceful unravelling where Reiner’s control of dynamics is all; the Adagio third movement gives off a miraculous stillness; some conductors get lost in the harmonic maze here. If the second movement allegro is not as punchy as, say, Karajan’s Berlin EMI performance, it still makes its effect and the spatial element works remarkably well.

Finally, the five Hungarian Sketches reveal, in the ‘Swineherd’s Dance’ at least, that Reiner could do unbuttoned as well. These are arrangements of piano pieces (Nos. 5 and 10 of Ten Easy Pieces, no. 2 of Four Dirges, no. 2 of Three Burlesques, and no. 40 of For Children, Book 1) that the composer made in an attempt to court popularity. The most memorable aspect of the present performances comes in the form of the outstanding solo clarinettist (in both the first and third movements). The Hungarian Sketches make for an interesting close to a disc that shows Reiner and his orchestra at the height of their powers, all presented in exemplary sound. Strongly recommended.“ (Colin Clarke, MusicWeb International)

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Fritz Reiner, conductor

Recorded in Orchestra Hall, Chicago, Tracks 1-5: recorded October 22, 1955;

Tracks 6-14: recorded December 28 and 29, 1958

Engineered by Lewis Layton

Produced by Richard Mohr

Digitally remastered

Chicago marked the confluence of two distinct, but intermingling musical strains in Chicago, IL, in the mid-'60s: an academic approach and one coming from the streets. Reed player Walter Parazaider (born March 14, 1945, in Chicago, IL), trumpeter Lee Loughnane (born October 21, 1946, in Chicago, IL), and trombonist James Pankow (born August 20, 1947, in St. Louis, MO) were all music students at DePaul University. But they moonlighted in the city's clubs, playing everything from R&B to Irish music, and there they encountered less formally educated but no less talented players like guitarist Terry Kath (born January 31, 1946, in Chicago, IL; died January 23, 1978, in Los Angeles, CA) and drummer Danny Seraphine (born August 28, 1948, in Chicago, IL). In the mid-'60s, most rock groups followed the instrumentation of the Beatles -- two guitars, bass, and drums -- and horn sections were heard only in R&B. But in the summer of 1966, the Beatles used horns on 'Got to Get You into My Life' on their Revolver album and, as usual, pop music began to follow their lead. At the end of the year, the Buckinghams, a Chicago band guided by a friend of Parazaider's, James William Guercio, scored a national hit with the horn-filled 'Kind of a Drag,' which went on to hit number one in February 1967.

That was all the encouragement Parazaider and his friends needed. Parazaider called a meeting of the band-to-be at his apartment on February 15, 1967, inviting along a talented organist and singer he had run across, Robert Lamm (born October 13, 1944, in New York, NY [Brooklyn]). Lamm agreed to join and also said he could supply the missing bass sounds to the ensemble using the organ's foot pedals (a skill he had not actually acquired at the time).

Developing a repertoire of James Brown and Wilson Pickett material, the new band rehearsed in Parazaider's parents' basement before beginning to get gigs around town under the name the Big Thing. Soon, they were playing around the Midwest. By this time, Guercio had become a staff producer at Columbia Records, and he encouraged the band to begin developing original songs. Kath, and especially Lamm, took up the suggestion. (Soon, Pankow also became a major writer for the band.) Meanwhile, the sextet became a septet when Peter Cetera (born September 13, 1944, in Chicago, IL), singer and bassist for a rival Midwest band, the Exceptions, agreed to defect and join the Big Thing. This gave the group the unusual versatility of having three lead singers, the smooth baritone Lamm, the gruff baritone Kath, and Cetera, who was an elastic tenor. When Guercio came back to see the group in the late winter of 1968, he deemed them ready for the next step. In June 1968, he financed their move to Los Angeles.

Guercio exerted a powerful influence on the band as its manager and producer, which would become a problem over time. At first, the bandmembers were willing to live together in a two-bedroom house, practice all the time, and change the group's name to one of Guercio's choosing, Chicago Transit Authority. Guercio's growing power at Columbia Records enabled him to get the band signed there and to set in place the unusual image the band would have. He convinced the label to let this neophyte band release a double album as its debut (that is, when they agreed to a cut in their royalties), and he decided the group would be represented on the cover by a logo instead of a photograph.

Chicago Transit Authority, released in April 1969, debuted on the charts in May as the band began touring nationally. By July, the album had reached the Top 20, without benefit of a hit single. It had been taken up by the free-form FM rock stations and become an underground hit. It was certified gold by the end of the year and eventually went on to sell more than two million copies. (In September 1969, the band played the Toronto Rock 'n' Roll Festival, and somehow the promoter obtained the right to tape the show. That same low-fidelity tape has turned up in an endless series of albums ever since. Examples include: Anthology, Beat the Bootleggers: Live 1967, Beginnings, Beginnings Live, Chicago [Classic World], Chicago Live, Chicago Transit Authority: Live in Concert [Magnum], Chicago Transit Authority: Live in Concert [Onyx], Great Chicago in Concert, I'm a Man, In Concert [Digmode], In Concert [Pilz], Live! [Columbia River], Live [LaserLight], Live Chicago, Live in Concert, Live in Toronto, Live '69, Live 25 or 6 to 4, The Masters, Rock in Toronto, and Toronto Rock 'n' Roll Revival.) To Guercio's surprise, he was contacted by the real Chicago Transit Authority, which objected to the band's use of the name; he responded by shortening the name to simply 'Chicago.' When he and the group finished the second album (another double) for release at the start of 1970, it was called Chicago, though it has since become known as Chicago II.

Chicago II vaulted into the Top Ten in its second week on the Billboard chart, even before its first single, 'Make Me Smile,' hit the Hot 100. The single was an excerpt from a musical suite, and the band at first objected to the editing considered necessary to prepare it for AM radio play. But it went on to reach the Top Ten, as did its successor, '25 or 6 to 4.' The album quickly went gold and eventually platinum. In the fall of 1970, Columbia Records released 'Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?,' drawn from the group's first album, as its next single; it gave them their third consecutive Top Ten hit.

Chicago III, another double album, was ready for release at the start of 1971, and it just missed hitting number one while giving the band a third gold (and later platinum) LP. Its singles did not reach the Top Ten, however, and Columbia again reached back, releasing 'Beginnings' (from the first album) backed with 'Colour My World' (from the second) to give Chicago its fourth Top Ten single. Next up was a live album, the four-disc box set Chicago at Carnegie Hall, which, despite its size, crested in the Top Five and sold over a million copies. (The band itself preferred Live in Japan, an album recorded in February 1972 and initially released only in Japan.) Chicago V, a one-LP set, released in July 1972, spent nine weeks at number one on its way to selling over two million copies, spurred by its gold-selling Top Ten hit 'Saturday in the Park.' Chicago VI followed a year later and repeated the same success, launching the Top Ten singles 'Feelin' Stronger Every Day' and 'Just You 'n' Me.'

The next Top Ten hit, '(I've Been) Searchin' So Long,' was released in advance of Chicago VII in the late winter of 1974. The album was the band's third consecutive chart-topper and another million-seller. 'Call on Me' became its second Top Ten single. Chicago VIII, which marked the promotion of sideman percussionist Laudir de Oliveira as a full-fledged bandmember, appeared in the spring of 1975, spawned the Top Ten hit 'Old Days,' and became the band's fourth consecutive number one LP. After the profit-taking Chicago IX: Chicago's Greatest Hits in the fall of 1975 came Chicago X, which missed hitting number one but eventually sold over two million copies, in part because of the inclusion of the Grammy-winning number one single 'If You Leave Me Now.' Chicago XI, released in the late summer of 1977, continued the seemingly endless string of success, reaching the Top Ten, selling a million copies, and generating the Top Five hit 'Baby, What a Big Surprise.' (Source: www.billboard.com)

Booklet für Bartók: Concerto for Orchestra; Music for Strings, Percussion & Celesta; Hungarian Sketches