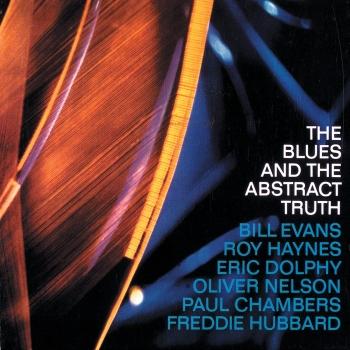

Evans, Haynes, Dolphy, Nelson, Chambers, Hubbard

Biographie Evans, Haynes, Dolphy, Nelson, Chambers, Hubbard

Oliver Nelson

Born June 4, 1932 in St. Louis, Oliver Nelson came from a musical family: His brother played saxophone with Cootie Williams in the Forties, and his sister was a singer-pianist. Nelson himself began piano studies at age six and saxophone at eleven. In the late Forites he played in various territory bands and then spent 1950–51 with Louis Jordan’s big band. After two years in a Marine Corps ensemble, he returned to St. Louis to study composition and theory at both Washington and Lincoln universities.

After graduation in 1958, Nelson moved to New York and played with Erskine Hawkins, Wild Bill Davis, and Louie Bellson. He also became the house arranger for the Apollo Theatre in Harlem. Though he began recording as a leader in 1959, Nelson’s breakthrough came in 1961 with The Blues and the Abstract Truth (Impulse), featuring an all-star septet that included Eric Dolphy, Bill Evans, and Freddie Hubbard. With the success of that deservedly acclaimed LP, Nelson’s career as a composer blossomed, and he was subsequently the leader on a number of memorable big-band recordings, including Afro-American (Prestige) and Full Nelson (Verve). He also became an in-demand studio arranger, collaborating with Cannonball Adderley, Johnny Hodges, Wes Montgomery, Jimmy Smith, Stanley Turrentine, and others.

During the Sixties, Nelson became one of the most strongly identifiable writing voices in jazz. In 1967, he moved to Los Angeles, where he became involved extensively in scoring for television and films. Though Nelson continued to write for jazz record dates and play (he focused on alto, tenor, and soprano saxophones at different times during the Sixties and Seventies), the demands of writing commercial music increased. The accompanying stress ultimately may have been his undoing; on October 28, 1975, he died suddenly of a heart attack. (Bill Kirchner) Excerpted from Oliver Nelson Verve Jazz Masters 48. (Source: Verve Music)

William John Evans

born in Plainfield, New Jersey, on August 16, 1929, Bill Evans died on September 15, 1980. The famed jazz pianist first won the Down Beat International Jazz Critics Poll in the New Star Piano category in 1958 and went on to win the poll several times thereafter, culminating in his posthumous induction into the magazine's Jazz Hall of Fame in 1981. He won seven Grammys for his recordings—Conversations with Myself (1963), The Bill Evans Trio Live at the Montreux Jazz Festival (1968), Alone (1970), two for The Bill Evans Album (1971), and I Will Say Goodbye and We Will Meet Again (1980)—and was posthumously awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1994.

Bill Evans began studying piano at the age of six and later took up both flute and violin. He received a music scholarship to Southeastern Louisiana College, graduated in 1950, and joined Herbie Fields's band the same year. A year later, he was drafted. He played flute in the Fifth Army Band at Fort Sheridan, spending his nights playing jazz piano in Chicago clubs. Released from the army in 1954, he began playing jazz in New York, where he joined the group of clarinetist Tony Scott.

That was the era of so-called 'Third Stream' music, the attempt at a fusion of jazz and classical music spearheaded by John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet, and the composer Gunther Schuller. Evans, with his classical training and jazz experience, was a natural for this music. Many of the Third Stream records and concerts of the time featured Evans, with his piano solo on the recording of George Russell's 'All About Rosie' a notable standout.

In 1959, Evans made the one step sure to bring him wider attention: he replaced Red Garland as pianist with the enormously influential Miles Davis Sextet, which, at the time, included John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley. Davis had felt that too many chords were cluttering up music; he wanted to work with scales and modes. Evans, partially influenced by Lennie Tristano, had been working along the same lines, and the result was one of the most influential albums ever made, Davis's Kind of Blue.

That same year, Evans formed his own trio. What he had in mind was not a piano with bass and drum accompaniment but a group in which all three voices would be as equal as possible. When he found the remarkable young bassist Scott LaFaro and drummer Paul Motian, that ideal was nearly achieved, but soon after, while make a classic series of landmark recordings at the Village Vanguard in New York, LaFaro was killed in an automobile accident. Thereafter, Evans worked with some of the finest bass players in jazz: Chuck Israels, Gary Peacock, Eddie Gomez, Michael Moore.

The Bill Evans Trio continued with bassist Michael Moore and Philly Joe Jones on drums. The first Bill Evans album for Warner Bros., however, in 1978, was a solo outing in the tradition of his earlier albums Conversations with Myself and Further Conversations with Myself. On the album, New Conversations, Evans solos and, through multi-tracking, accompanies himself on acoustic and electric keyboards. He went on to record three more records for the label: Affinity, We Will Meet Again, and You Must Believe in Spring.

In June 1980, three months before Evans's untimely death, bassist Marc Johnson and drummer Joe LaBarbera joined the 51-year-old pianist for four nights at New York's Village Vanguard. Evans intended to release a double LP culled form these sessions, and he supervised the initial mixing and editing of the tapes. It would take more than 15 years before this material would become available, in an exhaustive, chronologically sequenced six-CD set, on Warner Bros., titled Turn Out the Stars: The Final Village Vanguard Recordings. Jazz critic Gary Giddins hailed the unearthed work as 'an important find-the most lyrical of improvisers was revitalized by a new trio in his favorite jazz club.' The 2009 Nonesuch reissue contains the original packaging and liner notes, as well as the complete 1996 set.

Evans, whose soft, intricate, rhapsodic improvisations became the performance standard for his time, once said, 'I think jazz is the purest tradition in music this country has had. It has never bent to strictly commercial considerations and so it has made music for its own sake. That's why I'm proud to be part of it.'

In the liner notes to Evans's Warner Bros. label debut, New Conversations, Nat Hentoff wrote, 'Evans has become so deeply influential a force in jazz by sheer force of integrity.' Miles Davis, characteristically direct, once said of Evans: 'He plays the piano the way it should be played.' (Source: Warner Music)