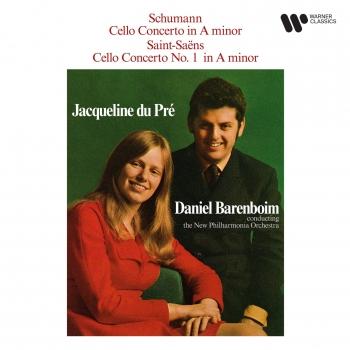

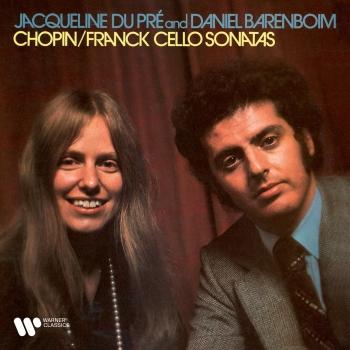

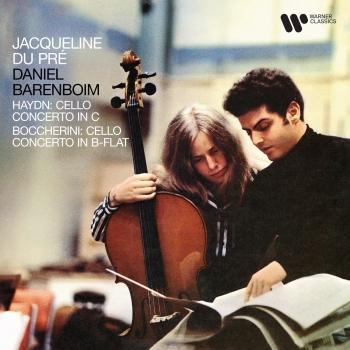

Jacqueline du Pré & Daniel Barenboim

Biographie Jacqueline du Pré & Daniel Barenboim

Jacqueline du Pré

Jacqueline's earliest cello tuition was from her mother who was a pianist, composer, conductor and school music teacher. She continued, aged five, with Alison Dalrymple at the London Violoncello School, following which her main teacher (both privately and at the Guildhall School of Music in London) was the celebrated William Pleeth, a great chamber musician and himself a pupil of W.H. Squire. Succeeding Rohan de Saram, du Pré became the second recipient of the Guilhermina Suggia Award. After taking lessons with Casals in 1960 she made her London début, continuing to study with Tortelier in Paris in 1962 and Rostropovich in the USSR in 1966. In 1962 came her concerto début in London with the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Rudolf Schwarz, playing Elgar’s Cello Concerto, a work that became pivotal in her short career. The following year she performed it under Malcolm Sargent at the BBC Proms and proved so popular that she repeated it in several further seasons (her 1964 performance is included here). Aged twenty she recorded it for EMI with Barbirolli in a recording that is often considered definitive and has never been out of print since its release. In the same year she performed the work with the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Antal Doráti for her United States début at Carnegie Hall.

Du Pré primarily played two Stradivarius cellos, a 1673 instrument now called the ‘du Pré’, and the 1712 ‘Davidov’, both gifts from her godmother, Ismena Holland. Many of her most famous recordings were made on the latter instrument.

Unsurprisingly for a protégé of Pleeth, du Pré was an avid chamber musician, performing with Yehudi Menuhin, Itzhak Perlman, Zubin Mehta, Pinchas Zukerman and Daniel Barenboim (whom she married in 1967). A 1969 London performance of Schubert’s ‘Trout’ Quintet was the basis of a film, The Trout, by Christopher Nupen, who made other films featuring du Pré, including Jacqueline du Pré and the Elgar Cello Concerto and The Ghost, with Barenboim and Zukerman in a performance of the Beethoven piano trio of that name. Du Pré was also the subject of a controversial book and film: A Genius in the Family (Heinemann, 1996), written by her siblings Piers and Hilary, upon which Hilary and Jackie, directed by Anand Tucker in 1998), was based.

In 1971 du Pré developed symptoms that were eventually diagnosed as those of multiple sclerosis. She made her last London appearances in February 1973, performing the Elgar Concerto with Zubin Mehta. She was honoured with several fellowships from music academies and honorary doctorate degrees from universities.

The story of du Pré’s life—of astonishing talent growing from a middle-class background, her ‘child-genius’ status, glamorous attachment to Barenboim and the tragic curtailing of her career due to a cruel and debilitating disease—is universally known, and her association with one work in particular further adds to her popular appeal (although she actually performed and recorded a wide range of solo repertoire). In hindsight her recordings reveal a musician very much of her time and yet imbued with an indefinable fire and spirit during a period when performance style had largely stabilised; when overtly Romantic stylistic traits (such as portamento) were spurned and others (such as vibrato) had reached a plateau of ubiquity. Listening to du Pré can be a vivid experience, but of course recordings cannot convey the visual impact of live performance, especially with an artist so physical in her emotional response to music.

The two Elgar Concerto recordings here are broadly similar in artistry and have largely defined modern performance conventions of this work. Du Pré begins in a fiery fashion—perhaps more so in the live performance, which is less polished technically—but her expansive approach is soon evident and stands in stark contrast to the simplicity of Beatrice Harrison under the composer’s baton in 1928. At times in the slow movement the performances do not sparkle in quite the way one might expect and it may be that this dimension is not easily conveyed without visual contact with this iconic performer. Both, however, have a passage of quite extraordinary beauty just before the final reprise of the opening theme in the finale; here there is an almost transcendental quality to the playing that epitomises du Pré’s reputation for leaving her audiences spellbound.

Included also is a fine Dvořák Concerto (1969) with an admirable blend of emotion and detail, and some works with piano that testify to du Pré’s fine control of tone. The Schumann Fantasiestücke (1962) show mastery of Romantic gestures in both Germanic and French traditions, whilst the Chopin Sonata (1971) is well balanced and concentrated. Rubbra’s Sonata (1962) was recorded at the last concert she gave with her mother at the piano and is an astonishingly mature performance conveying well Rubbra’s impassioned but dark and introspective musical language.

Untangling the qualities of du Pré’s playing from the legend of her life is ultimately impossible, but this selection of recordings unquestionably demonstrates her great prowess as one of the most vivid performers of her generation.