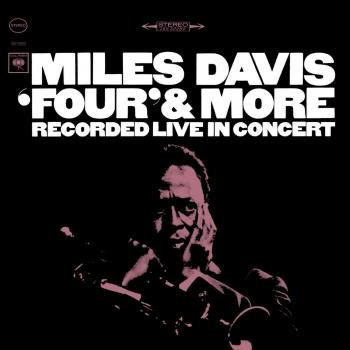

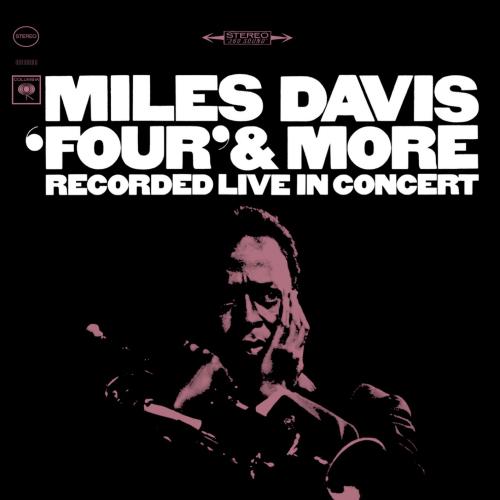

"Four" & More (2022 Remaster) Miles Davis

Album info

Album-Release:

1966

HRA-Release:

16.12.2022

Album including Album cover

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- 1 So What (Live at Philharmonic Hall, New York, NY - February 1964) 09:10

- 2 Walkin' (Live at Philharmonic Hall, New York, NY - February 1964) 08:08

- 3 Joshua (Live at Philharmonic Hall, New York, NY - February 1964) 09:32

- 4 Go-Go (Theme and Announcement) (Live at Philharmonic Hall, New York, NY - February 1964) 01:38

- 5 Four (Live at Philharmonic Hall, New York, NY - February 1964) 06:20

- 6 Seven Steps To Heaven (Live at Philharmonic Hall, New York, NY - February 1964) 07:45

- 7 There Is No Greater Love (Live at Philharmonic Hall, New York, NY - February 1964) 10:02

- 8 Go-Go (Theme and Announcement) (Version 2 - Live at Philharmonic Hall, New York, NY - February 1964) 01:21

Info for "Four" & More (2022 Remaster)

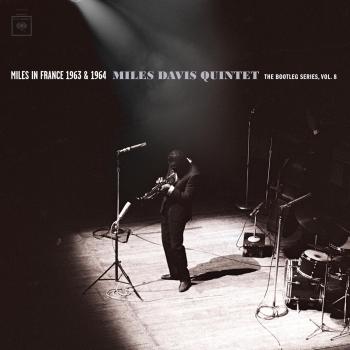

As successful as Miles’ Carnegie Hall concert had been in 1961, it was inevitable he would soon revisit the same setup: headline a venue of similar stature, sponsored by a worthy activist group, and record the performance for release. On February 12, 1964, he did exactly that at New York’s Philharmonic Hall, then just two years old and Valentine’s Day two days away. The concert was a benefit for not one, but three African-American NAACP, the Congress of Racial Equality and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

As rushed as Columbia Records was in 1961—Miles had initially resisted the idea of taping that concert—three years later all was ready and in line. The resulting recording impressed the label and included so much material that they released it as two separate LPs, dividing the material energy-wise.

My Funny Valentine was the ballads album—delicacy and down-tempo energy. “Four” & More held the high-energy burners, the power and propulsion. (Reissues in the CD era brought the music together in their original sequence.) Both were immediate critical successes. “Lickety split. Zippity do-dah. Burn, baby, burn,” was one historian’s description of the breath-catching hurtle of tunes like “Walkin’,” “Four,” and “So What.” “Profoundly felt emotion with the minimum of fuss and the maximum of restraint,” is how another wrote of “”All of You,” “All Blues,” and the love song Miles’ had been shaping and revisiting since the early 1950s: “My Funny Valentine.”

Simply put, the pair are a high-water mark on multiple levels: arguably Miles’ top live recording from the early 1960s—technically, musically, and historically. The recording captured the evening’s excitement in feel and sound; audience applause is thunderous. Miles’ most consistent group of that period were nearing their first anniversary together, road-honed and at a collective peak. Each added their part to an amazing whole: Herbie Hancock’s tune-defining piano intros, as on “My Funny Valentine.” George Coleman putting meat to the melodies on tenor, surfing the shifting rhythms he heard behind him—Latin, double-time, ballad. Ron Carter, his warm, legato bass sound, provided rhythmic punch and steadiness in support; check him behind Coleman’s on “I Thought About You.” And Williams drum surprises: like laying out on “Stella By Starlight,” then coming in with a yelp of excitement. Miles’ trumpet sound had never been more wide-ranging in character—powerful and brash at the opening of solos, hushed and unrushed playing his favorite melodies that leaned on his way of expressing vulnerability.

In his autobiography Miles recalled the night as much for the music as for the pre-show argument that erupted backstage when the band learned Miles had decided they were all donating their fee to the cause, without being asked. The news of no pay caused a collective and discernible outrage. “I think the anger created a fire, a tension that got into everybody’s playing, and maybe that’s one of the reasons everybody played with such intensity.”

Miles Davis, trumpet

George Coleman, tenor saxophone

Herbie Hancock, piano

Ron Carter, double bass

Tony Williams, drums

Digitally remastered

Trumpeter Miles Davis grew up in East St. Louis, Illinois, just across the river from St. Louis, Missouri. His parents were affluent, and had the means to support his musical studies as a boy. He began playing the cornet at age nine, and received his first trumpet at around twelve or thirteen. He studied classical technique, and focused mainly on using a rich, clear tone, something that helped define his sound in later years.

As a teenager, he played in various bands in St. Louis, which was rich with jazz, as big bands often stopped there on tours throughout the Midwest and southern states. The most important experience he had was when he was asked to play in the Billy Eckstine band for a week as a substitute. The group included Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Sara Vaughan. After playing with these stars, Davis knew he had to move to New York to be at the heart of the jazz scene.

In Pursuit of Parker:

In 1944 Davis moved to New York City where he had earned a scholarship to study trumpet at the Juilliard School of Music. Upon arriving however, he sought after Charlie Parker, and meanwhile spent all of his time in jazz clubs listening to bebop. He was transfixed on the music, and grew utterly bored with his classical studies. After less than a year at Juilliard, he dropped out and tried his hand at performing jazz.

Although not particularly stunning, his playing was good enough to finally attract Charlie Parker, and Davis joined his quintet in 1945. He was often criticized for sounding inexperienced, and was compared unfavorably to Dizzy Gillespie and Fats Navarro, who were the leading trumpeters at the time. Both boasted stellar technique and range, neither of which Davis possessed. In spite of this, he made a lasting impression on those who heard him, and his career was soon set aloft.

Cool Jazz and a Rise to Fame:

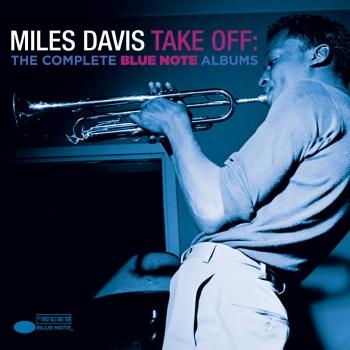

Encouraged by composer and arranger Gil Evans, Davis formed a group in 1949 that consisted of nine musicians, including Lee Konitz and Gerry Mulligan. The group was larger than most bebop ensembles, and featured more detailed arrangements. The music was characterized by a more subdued mood than earlier styles, and came to be known as cool jazz. In 1949 Davis released the album Birth of the Cool (Captiol Records).

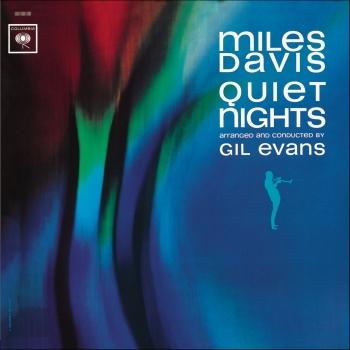

Change of artistic direction became central to Davis’ long and increasingly influential career. After dabbling in hard bop as a leader on four Prestige recordings featuring John Coltrane, he signed with Columbia records and made albums that featured Gil Evans’ arrangements for 19-piece orchestra. These were Miles Ahead, Porgy and Bess, Sketches of Spain, and Quiet Nights. He rose in popularity with these recordings, in part due to his signature sound, which he often enhanced by using a Harmon mute.

Kind of Blue and Beyond:

In 1959 Davis made his pivotal recording, Kind of Blue. It was a departure from all of his previous projects, abandoning complicated melodies for tunes that were sometimes only composed of two chords. This style became known as modal jazz, and it allows the soloist expressive freedom since he does not have to negotiate complex harmonies. Kind of Blue also featured John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, and Bill Evans. The album is one of the most influential in jazz, and is Columbia Records’ best-selling jazz record of all time.

In the mid 1960s Davis changed directions again, forming a group with Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Tony Williams, and Ron Carter. This group was known for the excellence of each individual member, and also for its unique performance approach. Each night the tunes would sound different, as the musicians would sometimes only loosely adhere to the song structures, and often transition from one right into the next. Each player was given the chance to develop his solos extensively. Like all of Davis’ previous groups, this quintet was highly influential.

Late Career:

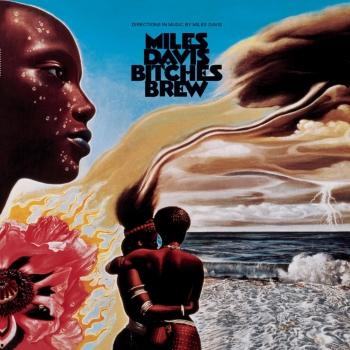

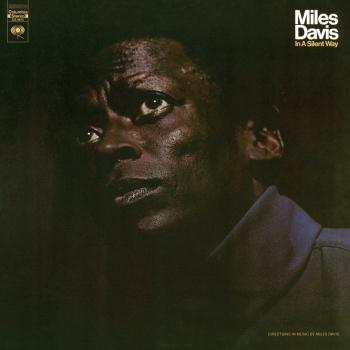

Despite health problems, drug addiction, and strained personal relationships, Davis continued to play, changing his approach with each new project. In the late 60s and 70s, he began to experiment with electronic instruments, and grooves that were tinged with rock and funk music. Two famous recordings from this period are In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew. By the time the 1980s rolled around, Davis was not only a jazz legacy, but a pop icon, whose music, persona, and fashion style were legendary.

Davis died in 1991, as perhaps the most influential jazz artist ever. His vast body of work continues to be a source of inspiration for today’s musicians. (Jacob Teichroew, About.com Guide)

This album contains no booklet.