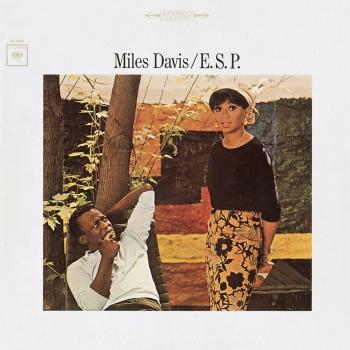

E.S.P. (2022 Remaster) Miles Davis

Album info

Album-Release:

1965

HRA-Release:

16.12.2022

Album including Album cover

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- 1 E.S.P. 05:29

- 2 Eighty-One 06:10

- 3 Little One 07:20

- 4 R.J. 03:56

- 5 Agitation 07:46

- 6 Iris 08:29

- 7 Mood 08:50

Info for E.S.P. (2022 Remaster)

Miles’ Second Great Quintet hit the ground running—perhaps skating more accurately describes the fluidity they achieved among them at an amazingly rapid rate. Wayne Shorter joined in September of 1964, and his watery approach on saxophone and his compositions—odd, snakelike themes and devious harmonic twists that still flowed organically—eventually proved a needed catalyst, the key that finally opened the door to Miles’ next musical leap forward.

At the end of their first five months together—after touring Europe in the final months of 1964 and a number of club dates that led them to the West Coast—Miles took Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams into the studio for the first time in January; E.S.P. was the result, the group’s debut.

For the first time since the Kind of Blue sessions in 1959, the material Miles recorded was all original and all generated from within the band, a step of self-reliance that would guide almost all the music they made together. It made sense—a new collective approach required new music. On recent albums, Miles’ focus seemed to have been redesigning old or new melodies and making room for solo statements. With his new quintet, the attention turned to the group performance; the excitement lay in the interplay between the members, their stop-and-go energy, the dramatic turns from density to openness, the subtle rhythmic and suggested harmonic shifts that bubbled behind the soloists. Then there’s the band’s sonic signature, that introspective, slightly dreamy feel they delivered even when the music was at full gallop—which it often was. Evidence of this priority lies in the remarkably consistent mood that ties together all the tracks on E.S.P., despite different members contributing their compositions.

Shorter’s tune “E.S.P.” sounds willfully abstract yet swings in the hands of the quintet, as does “Agitation,” a Miles modal number that opens with a spirited, chattering drum solo, and soon became the favored set-opener for the quintet. Shorter’s other contribution “Iris” serves as the album’s romantic offering, languidly lyrical. Hancock delivered one tune—“Little One”—that established a formula the quintet would come back to: pensive, rubato intro, waiting for a steady beat to lock onto. Three Carter tunes were recorded as well: the boogaloo-meets-hardbop feel of “Eighty One” (Hancock’s piano comping makes it pop), the break-filled, compositionally complex “R.J.” (named for his son,) and the reflective, aptly titled “Mood”, ideal for the ethereal effect Miles loved to explore with muted trumpet.

In looking back, E.S.P. stands out as the promise of something new; to ears hearing this music for the first time in 1965 some were taken aback, like Miles’ old friend trumpeter Kenny Dorham, who called the album “mostly brain music.” Other musicians were captivated by the apparent telepathy with which the quintet operated; the critics, inevitably, came around.

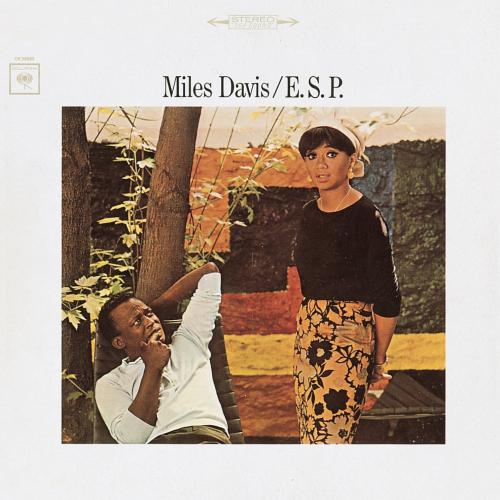

Two things about the original LP cover: on the back, one of the few jazz critics Miles respected, Ralph J. Gleason, had been asked yet again to pen liner notes. Rather than the standard expository essay or interview, Gleason opted to compose a poem in the style of e.e. cummings, using the titles of Miles tracks for his text. The front featured a photo taken in late summer of 1965, Miles seated in the garden behind his Manhattan townhouse, regarding his wife Frances quixotically; she stands near him but apart, gazing unsmiling into the camera. The image predicts their breakup; within a week she had left him.

Miles Davis, trumpet

Wayne Shorter, tenor saxophone

Herbie Hancock, piano

Ron Carter, bass

Tony Williams, drums

Digitally remastered

Trumpeter Miles Davis grew up in East St. Louis, Illinois, just across the river from St. Louis, Missouri. His parents were affluent, and had the means to support his musical studies as a boy. He began playing the cornet at age nine, and received his first trumpet at around twelve or thirteen. He studied classical technique, and focused mainly on using a rich, clear tone, something that helped define his sound in later years.

As a teenager, he played in various bands in St. Louis, which was rich with jazz, as big bands often stopped there on tours throughout the Midwest and southern states. The most important experience he had was when he was asked to play in the Billy Eckstine band for a week as a substitute. The group included Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Sara Vaughan. After playing with these stars, Davis knew he had to move to New York to be at the heart of the jazz scene.

In Pursuit of Parker:

In 1944 Davis moved to New York City where he had earned a scholarship to study trumpet at the Juilliard School of Music. Upon arriving however, he sought after Charlie Parker, and meanwhile spent all of his time in jazz clubs listening to bebop. He was transfixed on the music, and grew utterly bored with his classical studies. After less than a year at Juilliard, he dropped out and tried his hand at performing jazz.

Although not particularly stunning, his playing was good enough to finally attract Charlie Parker, and Davis joined his quintet in 1945. He was often criticized for sounding inexperienced, and was compared unfavorably to Dizzy Gillespie and Fats Navarro, who were the leading trumpeters at the time. Both boasted stellar technique and range, neither of which Davis possessed. In spite of this, he made a lasting impression on those who heard him, and his career was soon set aloft.

Cool Jazz and a Rise to Fame:

Encouraged by composer and arranger Gil Evans, Davis formed a group in 1949 that consisted of nine musicians, including Lee Konitz and Gerry Mulligan. The group was larger than most bebop ensembles, and featured more detailed arrangements. The music was characterized by a more subdued mood than earlier styles, and came to be known as cool jazz. In 1949 Davis released the album Birth of the Cool (Captiol Records).

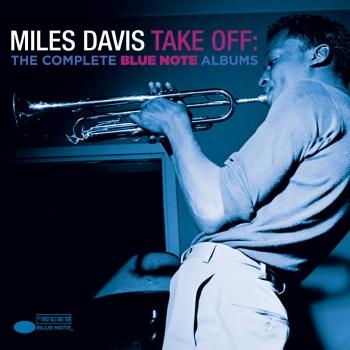

Change of artistic direction became central to Davis’ long and increasingly influential career. After dabbling in hard bop as a leader on four Prestige recordings featuring John Coltrane, he signed with Columbia records and made albums that featured Gil Evans’ arrangements for 19-piece orchestra. These were Miles Ahead, Porgy and Bess, Sketches of Spain, and Quiet Nights. He rose in popularity with these recordings, in part due to his signature sound, which he often enhanced by using a Harmon mute.

Kind of Blue and Beyond:

In 1959 Davis made his pivotal recording, Kind of Blue. It was a departure from all of his previous projects, abandoning complicated melodies for tunes that were sometimes only composed of two chords. This style became known as modal jazz, and it allows the soloist expressive freedom since he does not have to negotiate complex harmonies. Kind of Blue also featured John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, and Bill Evans. The album is one of the most influential in jazz, and is Columbia Records’ best-selling jazz record of all time.

In the mid 1960s Davis changed directions again, forming a group with Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Tony Williams, and Ron Carter. This group was known for the excellence of each individual member, and also for its unique performance approach. Each night the tunes would sound different, as the musicians would sometimes only loosely adhere to the song structures, and often transition from one right into the next. Each player was given the chance to develop his solos extensively. Like all of Davis’ previous groups, this quintet was highly influential.

Late Career:

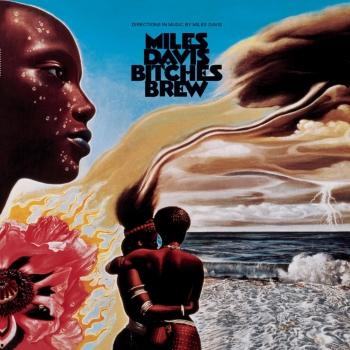

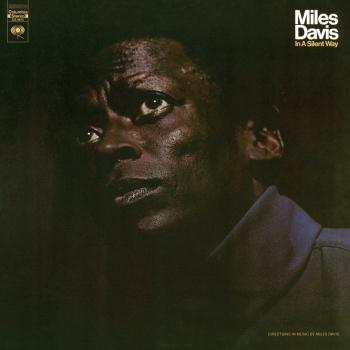

Despite health problems, drug addiction, and strained personal relationships, Davis continued to play, changing his approach with each new project. In the late 60s and 70s, he began to experiment with electronic instruments, and grooves that were tinged with rock and funk music. Two famous recordings from this period are In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew. By the time the 1980s rolled around, Davis was not only a jazz legacy, but a pop icon, whose music, persona, and fashion style were legendary.

Davis died in 1991, as perhaps the most influential jazz artist ever. His vast body of work continues to be a source of inspiration for today’s musicians. (Jacob Teichroew, About.com Guide)

This album contains no booklet.