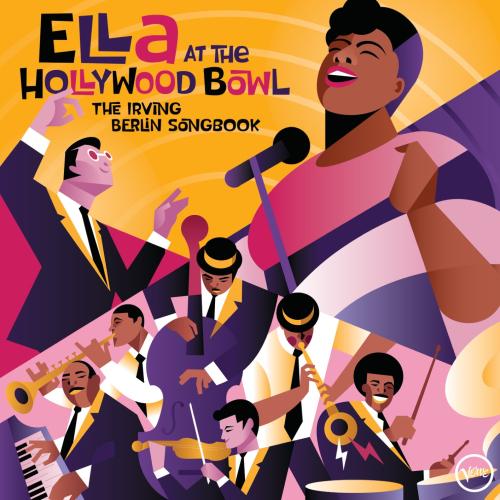

Ella At The Hollywood Bowl: The Irving Berlin Songbook Live (Remastered) Ella Fitzgerald

Album Info

Album Veröffentlichung:

2022

HRA-Veröffentlichung:

24.06.2022

Das Album enthält Albumcover

Entschuldigen Sie bitte!

Sehr geehrter HIGHRESAUDIO Besucher,

leider kann das Album zurzeit aufgrund von Länder- und Lizenzbeschränkungen nicht gekauft werden oder uns liegt der offizielle Veröffentlichungstermin für Ihr Land noch nicht vor. Wir aktualisieren unsere Veröffentlichungstermine ein- bis zweimal die Woche. Bitte schauen Sie ab und zu mal wieder rein.

Wir empfehlen Ihnen das Album auf Ihre Merkliste zu setzen.

Wir bedanken uns für Ihr Verständnis und Ihre Geduld.

Ihr, HIGHRESAUDIO

- 1 The Song Is Ended (Live) 02:14

- 2 You’re Laughing At Me (Live) 03:26

- 3 How Deep Is The Ocean (Live) 03:07

- 4 Heat Wave (Live) 02:01

- 5 Suppertime (Live) 03:13

- 6 Cheek To Cheek (Live) 03:26

- 7 Russian Lullaby (Live) 01:51

- 8 Top Hat, White Tie and Tails (Live) 02:47

- 9 I’ve Got My Love To Keep Me Warm (Live) 03:06

- 10 Get Thee Behind Me Satan (Live) 04:00

- 11 Let’s Face The Music And Dance (Live) 02:50

- 12 Always (Live) 03:15

- 13 Puttin’ On The Ritz (Live) 02:01

- 14 Let Yourself Go (Live) 02:21

- 15 Alexander’s Ragtime Band (Live) 03:04

Info zu Ella At The Hollywood Bowl: The Irving Berlin Songbook Live (Remastered)

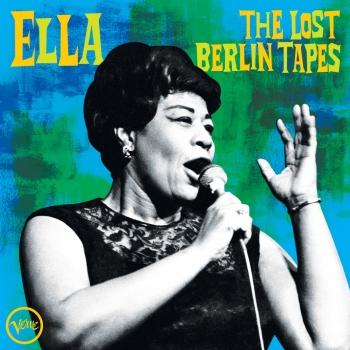

Es ist immer wieder verblüffend, was für Tonschätze erst viele Jahrzehnte nach ihrer Aufnahme in Firmen- und Privatarchiven von professionellen Wühlmäusen entdeckt werden. Gerade in der jüngeren Vergangenheit erblickten bislang unbekannte Meisterwerke von John Coltrane (“Both Directions At Once: The Lost Album”, “Blue World” und “A Love Supreme: Live In Seattle”), Thelonious Monk (“Palo Alto”), Charlie Parker (“Bird In LA”) und Ella Fitzgerald (“The Lost Berlin Tapes”) das Licht der Welt.

Jetzt gibt es mit “Ella At The Hollywood Bowl: The Irving Berlin Songbook” ein weiteres sensationelles Fundstück der “First Lady Of Song” aus dem Privatarchiv ihres Mentors und Produzenten Norman Granz.

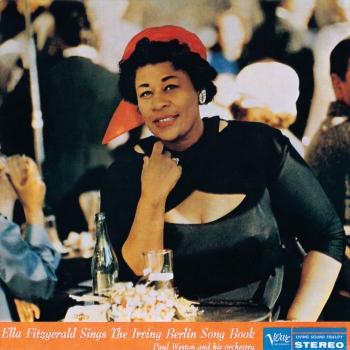

Das Album enthält einen absolut fantastischen Live-Mitschnitt, der am 16. August 1958 in der Hollywood Bowl entstanden war; nur fünf Monate nachdem die Sängerin für Verve Records das Doppelalbum “Ella Fitzgerald Sings The Irving Berlin Song Book” aufgenommen hatte. Dieses vierte Album der bahnbrechenden und unglaublich populären “Songbook”-Reihe brachte Ella am 4. Mai 1959 bei der allerersten Grammy-Verleihung gleich zwei Trophäen ein: für die “beste Jazzdarbietung eines Einzelkünstlers” und die “beste weibliche Gesangsdarbietung” in der Pop-Sparte. Darüber hinaus wurde das “Irving Berlin Songbook” auch für die Auszeichnung als “Album des Jahres” nominiert.

Mit einem von Paul Weston dirigierten und arrangierten Orchester präsentierte Ella in der restlos ausverkauften Hollywood Bowl 15 der 31 Songs des damals brandneuen Doppelalbums. Es sollte das einzige Konzert bleiben, bei dem sie die ikonischen Arrangements wie bei der ebenfalls von Weston geleiteten Studiosession mit einem vollen Orchester live aufführte. Auf dem Programm standen einige der bekanntesten Songs von Irving Berlin, darunter zeitlose Balladen wie “How Deep Is The Ocean?” und “Supper Time”, die Hollywood-Filmsongs “You’re Laughing At Me” und “Get Thee Behind Me Satan” sowie die swingenden Up-Tempo-Nummern “Cheek To Cheek”, “Top Hat”, “I’ve Got My Love To Keep Me Warm”, “Heat Wave” und “Puttin’ On The Ritz'”. Das restlos begeisterte Publikum inspirierte Ella an diesem Abend zu Darbietungen, die noch um einiges elektrisierender waren als jene der zuvor gemachten Studioaufnahmen.

Für die Abmischung der makellosen und klanglich üppigen Live-Tracks verwendete Gregg Field die originalen Viertelzoll-Bänder. Field, der für seine Arbeiten als Produzent und Toningenieur bereits mit acht Grammys ausgezeichnet wurde, hatte Ella Mitte der 80er Jahre als Schlagzeuger noch selbst auf Tourneen begleitet. Abgerundet wird das Album durch einen kenntnisreichen Begleittext des bekannten Jazzautors und Musikkritikers Will Friedwald über das Konzert und die gesamten Songbook-Serie. Die legendären Songbook-Alben, auf denen Ella in unvergleichlicher Art die besten Songs der größten US-amerikanischen Komponisten interpretierte, waren der Grundstein für den Verve-Katalog und setzten einen neuen, seither immer noch nicht übertroffenen Standard für Jazzgesangsaufnahmen.

Ella Fitzgerald, Gesang

The Hollywood Bowl Pops Orchestra

Paul Weston, Dirigent

Digitally remastered

Auszug aus dem Booklet von Will Friedwald: “The song is ended, but the melody lingers on.” The Roaring ’20s may have been “The Jazz Age,” but Irving Berlin, basking in the warm romantic glow of his recent (1926) marriage, composed some of his most heartfelt ballads – and waltzes no less – in this period, among them, “Always,” “Remember,” “All Alone,” “What’ll I Do?” and “Russian Lullaby.” Although it’s a song which, like many others, laments over a lost love, “The Song Is Ended” better describes a beginning, rather than an ending, in the actual chronology of the songwriter’s life. That’s why, quixotic as it might sound, it was appropriate for Ella Fitzgerald to open her set of Irving Berlin songs at the Hollywood Bowl on Saturday, August 16, 1958 with “The Song Is Ended.”

Thus, Fitzgerald chose to open this show with a song that most people would have thought of as a closer, and that’s not even one of the most remarkable aspects of this performance. More importantly, although she performed on numerous occasions in the Bowl, this is the first full-length set by Fitzgerald from this iconic venue to be released. For another, it’s the only time she worked in “public appearance” with Paul Weston, the gifted arranger-conductor of her Irving Berlin Songbook album. Most importantly this is an exceedingly rare occasion where Fitzgerald (or any of her contemporaries) took the repertoire from one of her studio albums and performed it live in concert – and at the Bowl no less – with the actual arranger who had done the album.

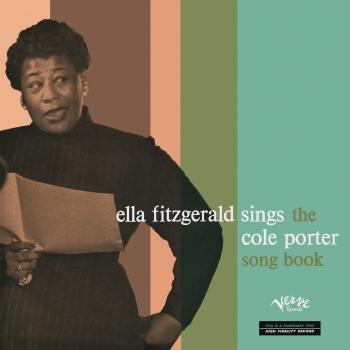

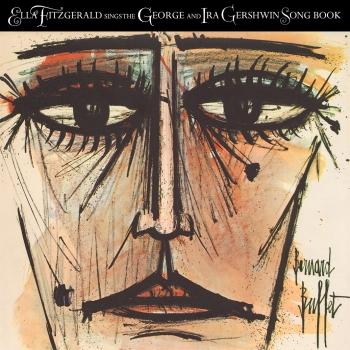

Actually, it was two albums that she performed live at the Bowl on this evening: the first half was titled “Ella Fitzgerald Sings Cole Porter,” which was followed by “Ella Fitzgerald Sings Irving Berlin.” (A year later, she would sing an entire evening of George and Ira Gershwin songs with Nelson Riddle, in anticipation of the next entry in the songbook series.) Exactly how and why Fitzgerald and her manager-producer Norman Granz decided to mount such a concert isn’t known. Fitzgerald’s live appearances followed several formats, and this wasn’t one of them. In her early big band years, roughly 1935 to 1942, she sang primarily in ballrooms, with the Chick Webb Orchestra (and subsequently with the same group under her own nominal leadership) for a mostly dancing audience, and also, occasionally, at movie theaters like the Apollo. During and after the war, she worked in supper clubs both of the mainstream and jazz variety as well as theaters. But even as her popularity and prestige increased to the point where she could work in formal concert halls, she mostly maintained the nightclub format – i.e. a mixed collection of songs without a specific theme (and certainly never deriving from a single album), usually accompanied by a trio. (When she toured with Jazz at the Philharmonic, the main difference was that, in addition to her own set, she would also do a few additional numbers with some of the headliners of the troupe in what the impresario described as a “jam session.”)

But to come on stage – with a full orchestra – and essentially sing the contents of a studio album, well, nobody did that. Not Sinatra, not Tony Bennett, not Miles Davis, nor any of the other key innovators who contributed to the development of what came to be known as “the concept album.” Even Duke Ellington only rarely performed a full-length work, such as one of his many “suites,” all the way through. (It wasn’t until years later that rock bands like the Who would make a point to tour playing the entirety of an album like Tommy – admittedly an extreme example.)

So exactly why did Fitzgerald and Granz choose to face this particular music and dance in this singular fashion? We may never know, but the logical answer is that the songbooks were proving to be such a major component to her burgeoning career that, for at least two years in a row, Fitzgerald and Granz were determined to do something special in honor of the ongoing series.

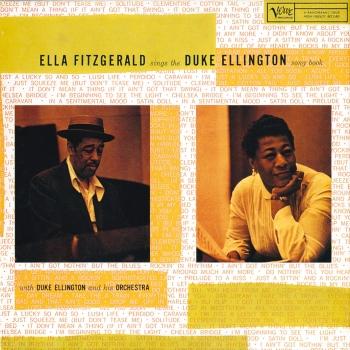

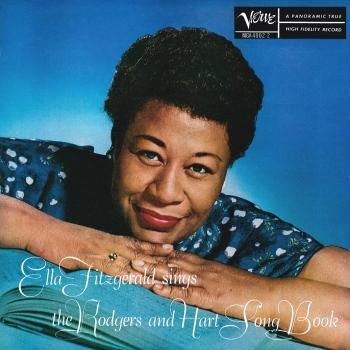

Ella’s first songbook album had been her original 10” Ella Sings Gershwin, produced by Milt Gabler, in 1950. When Granz was able to secure her exclusive recording contact in 1955, he immediately proceeded to build an entire new label – Verve Records – around her, with the songbook series as a foundational component of the Verve catalog. Indeed, all five of her first albums for the label (released in ’56 and ’57) were either songbooks or duet sessions with her longtime inspiration, Louis Armstrong. The songbook series was a major success commercially right from the git-go, but actually started somewhat tepidly in an artistic sense, in that the first two (Cole Porter and Rodgers and Hart) had arrangements by a decidedly lesser musical director. However, the series perked up considerably with the third, Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Duke Ellington Songbook, an ambitious four-LP package co-starring the Maestro and his orchestra.

The fourth, Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Irving Berlin Songbook, had been partly instigated by the songwriter himself, who was so impressed with the first three Songbook albums released thus far that he offered to cut his standard royalty rate in half. For the Berlin project, Granz recruited one of the best arranger-conductors then working in popular music, the formidable Paul Weston (1912–1996) and the results were impressive. Weston had first won his wings as a staff writer for Tommy Dorsey and then the Bob Crosby Orchestra, and then enjoyed long-term professional relationships with singers Dinah Shore and Jo Stafford, the latter becoming Mrs. Weston in 1952. His was the usual trajectory of an arranger-conductor in that period: big bands to popular singers and eventually to television (mostly variety shows), but his work was anything but average. Rather, Weston was a musical director in the same skill level as Sinatra’s two greatest collaborators, Axel Stordahl and Nelson Riddle.

As mentioned, Fitzgerald’s concert of August 16, 1958, was divided into two acts, “Ella Fitzgerald sings Cole Porter” and “Ella Fitzgerald Sings Irving Berlin.” Both halves opened with instrumental music – as a kind of an overture – conducted by Weston. Act One commenced with a “Cole Porter Overture” by Robert Russell Bennett, at that time long Broadway’s most celebrated orchestrator, along with Weston arrangements of two Porter songs. Act Two began with Weston playing Berlin’s “Blue Skies” as well as excerpts from his own extended work, Crescent City Suite, recently released by Columbia Records.

The officially-released recording of these arrangements, the Berlin Songbook, as issued by Verve in 1958, was one of Fitzgerald’s strongest albums thus far, but as outstanding as her studio work always was, her live concerts were just better: livelier, more energetic and more ebullient. Like all of her colleagues and peers (especially Sinatra and Nat Cole), Fitzgerald always fed off the energy and enthusiasm of the crowds in front of her. (It’s hardly a surprise that the best-remembered album of her entire career was probably her iconic 1960 Berlin concert recording.)

Thus, the ballads, among them such classics as “How Deep Is the Ocean?” and “Supper Time,” as well as such lesser-known Berlin Hollywood tunes as “You’re Laughing at Me” and “Get Thee Behind Me Satan,” are more openly emotional and moving. Two mid-’20s waltzes, “Always” and “Russian Lullaby” (a 16-bar minor key masterpiece) are amazingly effective. One wishes she had kept the latter in her repertoire; a rare example of Fitzgerald using wordless singing to comfort an infant rather than ignite a roaring crowd, it might have been another “Summertime” for her.

But though she was a supreme balladeer, The First Lady of Song was always more celebrated for her swinging uptempo numbers, as represented here by “Cheek to Cheek,” “Top Hat,” “I’ve Got My Love to Keep Me Warm” (“warm, warm, warm!”), the exotic “Heat Wave” (which is also warm, warm, warm!), “Puttin’ on the Ritz” (“well, I changed that melody!” she says afterwards), and “Let Yourself Go” (“Wail!” she exhorts to a muted trumpet soloist). “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” is a uniquely conceptual arrangement by Weston, which contrasts the agitated 2/4 of 1911-style dixieland with smoother, contemporary style “cool” jazz – it’s very specific to its era without being dated.

As mentioned, the Berlin half of the concert began with Paul Weston playing his own instrumental arrangement of “Blue Skies” – which opens the door to a mini-mystery involving that archetypical Berlin song. Fitzgerald and Weston recorded it, along with 31 other Berlin songs, at the fourth of five sessions devoted to the album in March 1958. Yet for whatever reason, “Blue Skies” wasn’t included in the original US issue of the album (either on the mono or stereo editions) though it was restored years later. (That same track of “Blue Skies,” however, was included as part of Fitzgerald’s Get Happy album in 1959.)

Of the 32 Berlin songs recorded for the project (15 of which were performed at this Bowl concert), “Blue Skies” was the album’s major scat feature – and one of Fitzgerald’s all-time greatest. (Making it all the more curious that it wasn’t used on the original album.) But since “Blue Skies” was absent from both the original double album and the Bowl concert, the decision was made to increase the scattiness quotient of “The Song Is Ended.” Even more than on the album, the live treatment of “The Song is Ended” repurposes Berlin’s melancholy waltz into an exuberant 4/4 swinger, complete with brief wordless episodes.

The transformation is so complete that it makes perfect sense that she would use it for an opener rather than a closer – underscored by the way she repeats “the melody lingers on…and on…and on.…” Even though it’s usually performed as a sad song, Fitzgerald shows how it works just as well as a joyous ode to the very act of making music; how better to take our happiness while we may? The title may tell us that the tune has concluded, but the woman whom Mel Torme christened “The High Priestess of Song,” is showing us precisely the opposite. (In fact, the tapes of the 1958 Cole Porter material, as well as the entire 1959 Gershwin-Nelson Riddle concert, will hopefully be issued sooner rather than later.) The song, and the adventure of making music with Ella Fitzgerald, are just beginning.

Ella Fitzgerald (1917-1996)

Am 25. April 2007 wäre Ella Fitzgerald, die beliebteste Jazz-Sängerin aller Zeiten, 90 Jahre geworden. Zum Jubiläum veröffentlicht Verve "We All Love Ella", ein spektakuläres All-Star-Tribute an die unvergessene Ella. Unter der Regie von Produzent Phil Ramone interpretieren Michael Bublé, Diana Krall, Stevie Wonder, Chaka Khan und viele andere die beliebtesten Ella-Songs. Außerdem greift das Label ganz tief in die Schublade und befördert einen echten Live-Leckerbissen nach langer Zeit wieder ans Tageslicht: "Ella in Hamburg"!

Über ein halbes Jahrhundert lang verkörperte Ella Fitzgerald das Idealbild der swingenden Jazzsängerin schlechthin. Unterstrichen wird ihre herausragende Stellung durch 14 Grammy-Auszeichungen und eine Bilanz von über 40 Millionen verkauften Alben. Alle lieben Ella - die Fans, die Kritiker, die Musiker, mit denen sie spielte, und nicht zuletzt all ihre Gesangskollegen und Kolleginnen. Als "First Lady Of Song" ist die 1996 gestorbene Sängerin in die Jazzgeschichte eingegangen. Diesen Titel verdankt sie vor allem den grandiosen Songbook-Alben, die sie zwischen 1956 und 1964 für Norman Granz und sein Label Verve aufnahm.

Die am 25. April 1917 in Newport News/Virginia geborene und in armen Verhältnissen aufgewachsene Ella Fitzgerald schaffte ihren Sprung ins professionelle Lager am 21. November 1934 bei einem Amateurtalentwettbewerb im legendären Apollo Theater in Harlem. Der Altsaxophonist Benny Carter, der den Auftritt der 17jährige gesehen hatte, empfahl sie dem Bandleader und Schlagzeuger Chick Webb, der gerade nach einer neuen Sängerin suchte. Webb war von der Erscheinung Ellas zunächst gar nicht begeistert, gab ihr dann aber trotzdem eine Chance. Und die verstand Ella zu nutzen. Schon wenig später trat der "ungeschliffene Diamant" (wie sie Webbs Trompeter Mario Bauzá damals nannte) mit Webbs Orchester im Savoy Ballroom auf und machte mit der Band auch die ersten Aufnahmen. Mit "A-Tisket, A-Tasket" landete sie 1938 ihren ersten Riesenerfolg. Die Nummer avancierte zur Hymne der Swingära.

Als Chick Webb im Juni 1939 starb, übernahm Ella, die längst zum eigentlichen Zugpferd des Orchesters aufgestiegen war, offiziell die Leitung. Als das Orchester 1941 nach einer weniger erfolgreichen Phase aufgelöst wurde, begann Ella ihre Solokarriere und unterschrieb einen langfristigen Vertrag bei dem Label Decca. Für Decca nahm sie in den folgenden Jahren mit Partnern wie dem singenden Altsaxophonisten Louis Jordan oder beliebten Doo-Wop-Gesangsensembles wie den Delta Rhythm Boys und den Ink Spots zahlreiche Hits auf.

1946 begann sie die Zusammenarbeit mit dem Jazz-Impresario und Plattenproduzenten Norman Granz, der sie regelmäßig bei seinen "Jazz At The Philharmonic"-Konzerten auftreten ließ. Zehn Jahre lang kümmerte sich Granz als Agent um Ella, bis er sie endlich bei der Decca loseisen und für sein eigenes Label Verve unter Vertrag nehmen konnte. Unter der Obhut von Granz trat Ella, die sich nach sechs Jahren Ehe 1953 von dem Bassisten Ray Brown getrennt hatte, nun in ihre kreativste Phase: Zwischen 1956 und 1964 nahm sie für Verve u.a. eine sensationelle Reihe mit Songbook-Einspielungen auf, die den Komponisten und Textdichtern Cole Porter, Richard Rodgers und Lorenz Hart, Duke Ellington, Irving Berlin, George und Ira Gershwin, Harold Arlen, Jerome Kern und Johnny Mercer gewidmet war. Legendär sind auch das "Porgy & Bess"-Album, das sie gemeinsam mit Louis Armstrong aufnahm, oder das Live-Album "Ella In Berlin", auf dem die Sängerin den Text des Songs "Mack The Knife" vergessen hatte und sich mit Improvisation brillant aus der Klemme rettete. "Nahezu all ihre Verve-Einspielungen sind die Anschaffung wert", bilanzierte der amerikanische Kritiker Scott Yanow.

Nach den Verve-Jahren unternahm Ella mit Einspielungen für andere Labels weniger geglückte Versuche, mit der Interpretation zeitgenössischer Popsongs ein neues Publikum zu gewinnen. Erst als Norman Granz, der Verve mittlerweile an MGM abgetreten hatte und in der Schweiz wohnte, ein neues Label namens Pablo aufbaute und die Sängerin erneut zu sich holte, konnte sie wieder an die brillanten Aufnahmen und Erfolge anknüpfen, die sie zuvor bei Verve erlebt hatte. Für Pablo nahm Ella in den 70er und 80er Jahren u.a. noch einige exzellente Alben mit Count Basie, Joe Pass und Oscar Peterson auf.

1994 zog sich Ella Fitzgerald ganz aus dem Musikbusiness zurück. Zwei Jahre später, am 15. Juni 1996, starb sie im Alter von 81 Jahren in Beverly Hills.

Dieses Album enthält kein Booklet