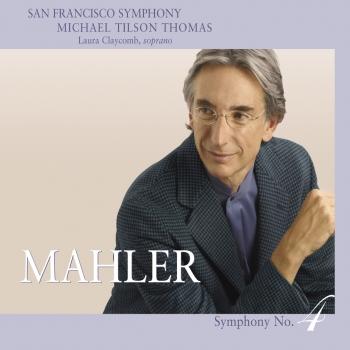

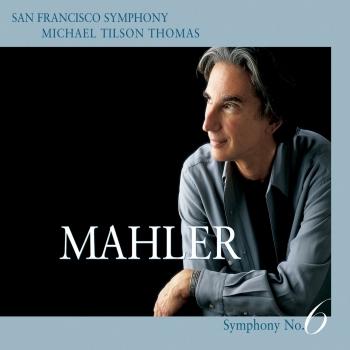

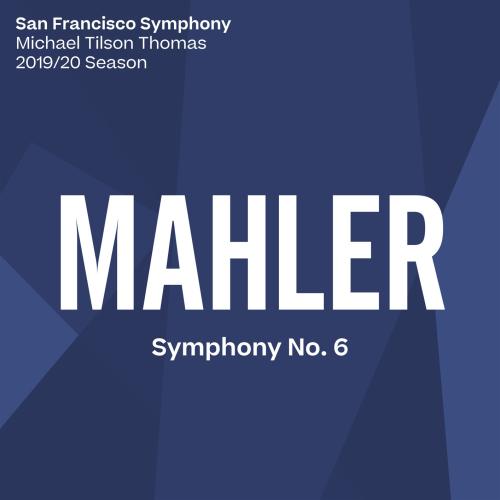

Mahler: Symphony No. 6 San Francisco Symphony & Michael Tilson Thomas

Album info

Album-Release:

2020

HRA-Release:

10.01.2020

Album including Album cover

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- Gustav Mahler (1860 - 1911): Mahler: Symphony No. 6 in A Minor:

- 1 Mahler: Symphony No. 6 in A Minor: I. Allegro energico, ma non troppo. Heftig, aber markig 24:37

- 2 Mahler: Symphony No. 6 in A Minor: II. Scherzo (Wuchtig) 13:32

- 3 Mahler: Symphony No. 6 in A Minor: III. Andante moderato 16:19

- 4 Mahler: Symphony No. 6 in A Minor: IV. Finale. Allegro moderato - Allegro energico 32:02

Info for Mahler: Symphony No. 6

Mahler begins with a grim march (Allegro energico, ma non troppo. Vehement, but vigorous). We feel the tramp before we hear the band, but it takes only five measures of fierce crescendo before the music is hugely present. Then, over a diminishing snare drum roll, two timpanists beat a left . . . left . . . left-right-left march cadence. Over that, three trumpeters sound a chord of A major. They too make a diminuendo, and halfway down, the chord changes from major to minor (as the trumpets get softer, three oboes, playing the same notes, make a crescendo). That is all. “Fate” or “tragedy”—no words say it as surely as the music. A complete swing-about in mood comes with a fervent melody that Alma said was intended to represent her.

“Alma,” in tender decrescendo, brings the exposition to a close. For a long time, the marchers dominate the development. Then Mahler withdraws to mountain heights. Celesta and divided violins play mysterious chord sequences, beautifully blurred by the sound of distant cowbells. “The last greeting from earth to penetrate the remote solitude of the mountain peaks,” Mahler said. The awakening from this vision is sudden and unkind. “Alma” reappears in due course, and in fact the movement ends with “herself” in a gesture of unbridled triumph.

Sharing motivic material with the first movement, the Scherzo too begins with stabbing detached low A’s, and it is in A minor. But where in the first movement those low A’s provided a grimly regular one-two-three-four framework, here rhythmic dissension reigns from the beginning. The trio, which comes around twice, is of an extreme metrical irregularity and in that sense one of Mahler’s most forward-looking pages. Alma Mahler heard in it “the arrhythmical play of little children.”

After this music of disintegration and suppressed violence, the Andante moderato is balm. The inspired melody is a marvel of subtle phrasing, magically scored, with dabs of wind color finely setting this or that point on the melodic curve into higher relief. Here is music full of Mahlerian major-minor ambiguities. The movement as a whole is of surprising harmonic sweep, its climax placed in faraway, luminous E major, and for that arrival Mahler brings back the mysterious sound of the cowbells.

Mahler’s final intentions concerning the order of these two middle movements are not entirely clear. The autograph puts the Scherzo before the Andante, as does the first printing, which preceded the first performance. For that performance, however, as well as for the second edition, Mahler reversed this order. One reads consistently that he eventually wished the original order restored, and Erwin Ratz in his brief editorial report for the Critical Edition simply states this as a fact, but there is no hard and direct evidence for it. Musically, the case for having the Scherzo precede the Andante is strong and threefold. One: The Scherzo’s impact as a kind of parody of the first movement is greater if it follows that movement immediately. Two: The respite provided by the Andante is more telling when it is offered after the double impact of the first and second movements and just before the emotionally taxing finale. Three: The key relationships (whose impact we all feel even if we cannot put a name to it) are more effective.

With this we come to the Finale (Allegro moderato—Allegro energico). This last movement is not much longer than the first; but, longer than the second and third movements together, it feels big—and it is meant to. The Finale of the Sixth Symphony surpasses the earlier movements in richness of musical event and in the oppressiveness of the emotional substance it lays upon the listener.

From the thud of a low C there arises an encompassing swirl of strangely luminous dust—harp glissandos, a woodwind chord, chains of trills on muted strings. It is terrifying because it is alien, and it is alien because with one exception, everything in the symphony thus far has been lucidly and sharply defined. The exception is the unearthly episode with the cowbells in the first movement. That was a beatific moment; this is its inverse, music of enveloping terror. The first violins detach themselves from this nebula to declaim a wide-ranging phrase of impassioned recitative, which, in its descent, collides with a specter we have not met in some time—the major chord that turns to minor (trumpets and trombones together this time) and the drummers with their fierce marching cadence. And as this recedes, the low strings come slowly to rest on a low A.

These sixteen measures, not much more than half a minute of music, also define the Finale’s harmonic task. The primacy of the symphony’s central key, A minor, must be re-established. Mahler’s finale is a design not only of great breadth, but of astonishing originality. Its formal point of reference is the familiar sonata plan of introduction, the exposition of material, its development, its restatement or recapitulation, and coda. This is, however, realized in a totally original way. The introduction, itself a complex sequence of events of which the nebula-plus-“fate”-chord is but the first, reappears, always varied, its components redistributed, at each major juncture of the movement.

Let me describe the piece in another way. From the introduction, the music gradually breaks through once again to the world of marches. The hero goes forth to conquer, but in the full flood of confidence and exaltation a hammer-blow strikes him down. This is literally a hammer-blow, for which Mahler wants the effect of a “short, powerful, heavy-sounding blow of non-metallic quality, like the stroke of an ax.” The music gathers energy, the forward march becomes even more determined, even frenzied in its thrust, only to be halted again by a second hammer-blow.

In Mahler’s original conception, a third hammer-blow coincided with the A major “fate” chord at the last appearance of the introductory dust-storm, but he eliminated it in his revision and probably did not restore it. The irrepressibility of that monstrous introduction is enough. On its last appearance, this begins in A minor, and the “fate” chord is the last A major that we hear. Over a long drum roll that relentlessly glues the music to A minor, trombones and tuba stammer fragments of funeral music. The symphony comes to a halt, recedes into inaudibility. The final, brutal tragic gesture is a sudden blast of A minor—not even the false hope of an A major beginning this time—and, behind it, the drummers’ last grim tattoo. (Michael Steinberg)

San Francisco Symphony

Michael Tilson Thomas, conductor

San Francisco Symphony

The San Francisco Symphony, widely considered to be among the most artistically adventurous and innovative arts institutions in the U.S., celebrated its Centennial season in 2011-12. The Orchestra was established by a group of San Francisco citizens, music-lovers, and musicians in the wake of the 1906 earthquake, and played its first concert on December 8, 1911. Almost immediately, the Symphony revitalized the city's cultural life. The Orchestra has grown in stature and acclaim under a succession of distinguished music directors: American composer Henry Hadley, Alfred Hertz (who had led the American premieres of Parsifal, Salome, and Der Rosenkavalier at the Metropolitan Opera), Basil Cameron, Issay Dobrowen, the legendary Pierre Monteux (who introduced the world to Le Sacre du printemps and Petrushka), Enrique Jordá, Josef Krips, Seiji Ozawa, Edo de Waart, Herbert Blomstedt (now Conductor Laureate), and current Music Director Michael Tilson Thomas (MTT). Led by Tilson Thomas, who begins his nineteenth season as Music Director in 2013-14, the SFS presents more than 220 concerts annually, and reaches an audience of nearly 600,000 in its home of Davies Symphony Hall, through its multifaceted education and community programs, and on national and international tours.

Since Tilson Thomas assumed his post as the SFS's eleventh Music Director in September 1995, he and the San Francisco Symphony have formed a musical partnership hailed as one of the most inspiring and successful in the country. His tenure with the Orchestra has been praised for outstanding musicianship, innovative programming, highlighting the works of American composers, and bringing new audiences to classical music. In addition, the Orchestra has been recognized nationally and internationally as a leader in music education and for the use of multimedia, television, technology, and the web to make classical music available worldwide to as many people as possible. MTT now is the longest-tenured music director for a major American orchestra, and the longest-serving music director in the San Francisco Symphony's history.

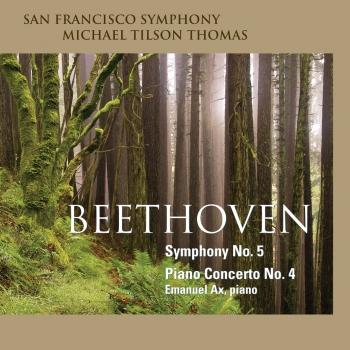

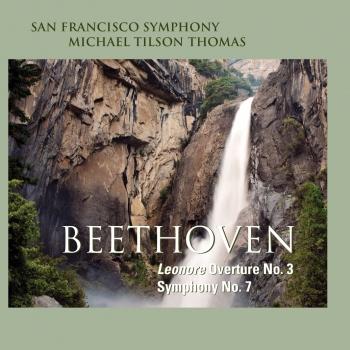

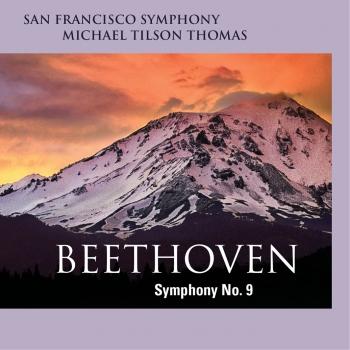

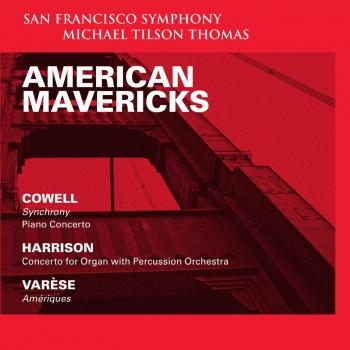

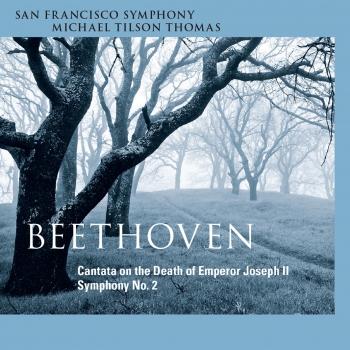

In its Centennial season, the Orchestra reprised its acclaimed American Mavericks Festival of music by pioneering modern American composers, featuring the world premieres of four commissioned works in two weeks of concerts at Davies Symphony Hall and on a two-week national tour, including four performances at Carnegie Hall. The San Francisco Symphony regularly mounts special weeklong semi-staged productions with multimedia, hosted and curated by MTT, and in 2012-13 presented specially staged performances of Grieg's Peer Gynt and the first concert performances by an orchestra of the complete music from Bernstein's West Side Story, which were recorded for release on SFS Media. Tilson Thomas and the Orchestra also dedicated several weeks to explorations of the music of Beethoven, selections of which were recorded for SFS Media, and Stravinsky, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the premiere of his Rite of Spring.

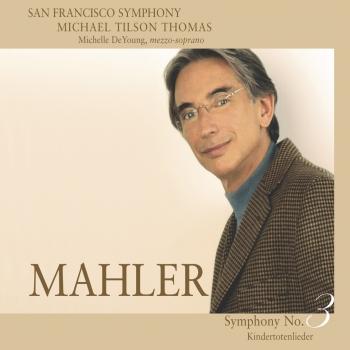

Since 1996, when Tilson Thomas led the Orchestra on the first of their more than a dozen national tours together, they have continued an ambitious yearly touring schedule that takes them to Europe, Asia and throughout the United States. In March 2014 they return to Europe for a three-week tour performing repertoire from the SFS Media catalogue including John Adams' Absolute Jest, Ives' A Concord Symphony, Mahler's Symphony No. 3, and Berlioz' Symphonie fantastique at two concerts each in London, Paris, and Vienna, and performances in Prague, Geneva, Luxembourg, Dortmund, and Birmingham. In 2012, they performed during a two-week national American Mavericks tour and a two-week tour of Asia with pianist Yuja Wang in Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Tokyo, Taipei, and Macau. In 2011, they made a three-week tour of Europe, culminating in Vienna performances of three Mahler symphonies to commemorate the anniversaries of the composer's birth and death. Recent touring highlights also include a three-week 2007 European tour that featured two televised appearances at the BBC Proms in London and concerts at several other major European festivals.

The Orchestra's recording series on SFS Media continues to reflect the artistic identity of its programming, including its commitment to performing the work of American maverick composers alongside that of the core classical masterworks. The San Francisco Symphony has recorded works from the American Mavericks Festival

concerts by Henry Cowell, Lou Harrison, and Edgard Varèse with pianist Jeremy Denk and organist Paul Jacobs, and won a 2013 Best Orchestral Performance Grammy award for its recording of John Adams' Harmonielehre and Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Other recently recorded works include Beethoven's Symphonies No. 5, 7, 9, and Piano Concerto No. 4, with soloist Emanuel Ax; Ives' A Concord Symphony; and Copland's Organ Symphony with Paul Jacobs. A live performance of John Adams' Absolute Jest with the St. Lawrence String Quartet and the Orchestra was recorded for future release on SFS Media, and live performances of Beethoven's Symphony No. 2 and Cantata on the Death of Emperor Joseph II was released in November 2013. Tilson Thomas and the Orchestra have recorded all nine of Gustav Mahler's symphonies and the Adagio from the unfinished Symphony No. 10, and the composer's works for voices, chorus, and orchestra for SFS Media. Their 2009 recording with the SFS Chorus of Mahler's sweeping Symphony No. 8, Symphony of a Thousand, and the Adagio from Symphony No. 10 won three Grammy awards, including Best Classical Album and Best Choral Performance. Other significant recordings include scenes from Prokofiev's Romeo and Juliet, a collection of Stravinsky ballets, a Gershwin collection, and Charles Ives: An American Journey, among others. In addition to fifteen Grammy awards, seven of them for the Mahler cycle, the SFS has won some of the world's most prestigious recording awards, including Japan's Record Academy Award, France's Grand Prix du Disque, and Germany's ECHO Klassik Award.

Tilson Thomas and the SFS launched the national Keeping Score PBS television series and multimedia project in 2006 to help make classical music more accessible to people of all ages and musical backgrounds. The project, an unprecedented undertaking among orchestras, is anchored by eight composer documentaries, hosted by Tilson Thomas, and eight live concert films; it also includes www.keepingscore.org, an innovative website to explore and learn about music; a national radio series; documentary and live performance DVD and CDs; and an education program for K-12 schools to further teaching through the arts by integrating classical music into core subjects. More than six million people have seen the Keeping Score television series, and the radio series has been broadcast on almost 100 stations nationally.

The San Francisco Symphony provides the most extensive education programs offered by any American orchestra today. In 1988, the Symphony established Adventures in Music (AIM), a free, comprehensive music education program that reaches every first- through fifth-grade child in the San Francisco Unified School District. The SFS Instrument Training and Support program reaches students in all San Francisco public middle and high schools with instrumental music programs, providing coaching by professional musicians. The Symphony expanded its educational offerings in 2011-12 with Community of Music Makers, a program that supports amateur choral singers and instrumental musicians with professional coaching by SFS musicians, rehearsals, and other learning opportunities. In development is a revitalized children's music education website, www.sfskids.org, created in conjunction with the UC Irvine Center for Computer Games and Virtual Worlds. The SFS also offers opportunities to hear and learn about great music through its programs Concerts for Kids, Music for Families, the internationally-acclaimed SFS Youth Orchestra, and annual free and community concerts.

This album contains no booklet.